tl;dr: it's a job for the miniPHY.

__________________

.

Optimising bandwidth in a noisy environment is a difficult problem, that Shannon and others have fought for decades.

There is this compromise, or dilemma, of detection versus correction : detection takes half the size of correction and since the miniMAC works as point-to-point with low latency, retransmit seems to be the simplest and lowest-effort strategy. For now the miniMAC is optimised for early detection with only 1/9th of bandwidth overhead.

This is adapted when there is relatively low noise. miniMAC should still work with moderate noise though. So I'm shopping for a low-density error correction layer, which could go between the PHY and the MAC. Maybe this could be dynamically bypassed and/or optional, so it becomes active when the error rate exceeds a certain level, because it would eat bandwidth too.

What bandwidth would be OK ? Another 1/8th gets us into the Hamming SECDED territory (64+8=72 bits) but it can correct only one bit per block. However, the line code might use multi-bit symbols with a mapping that maximises error diffusion, to speed up detection, so the slightest blip would alter several bits and be unrecoverable.

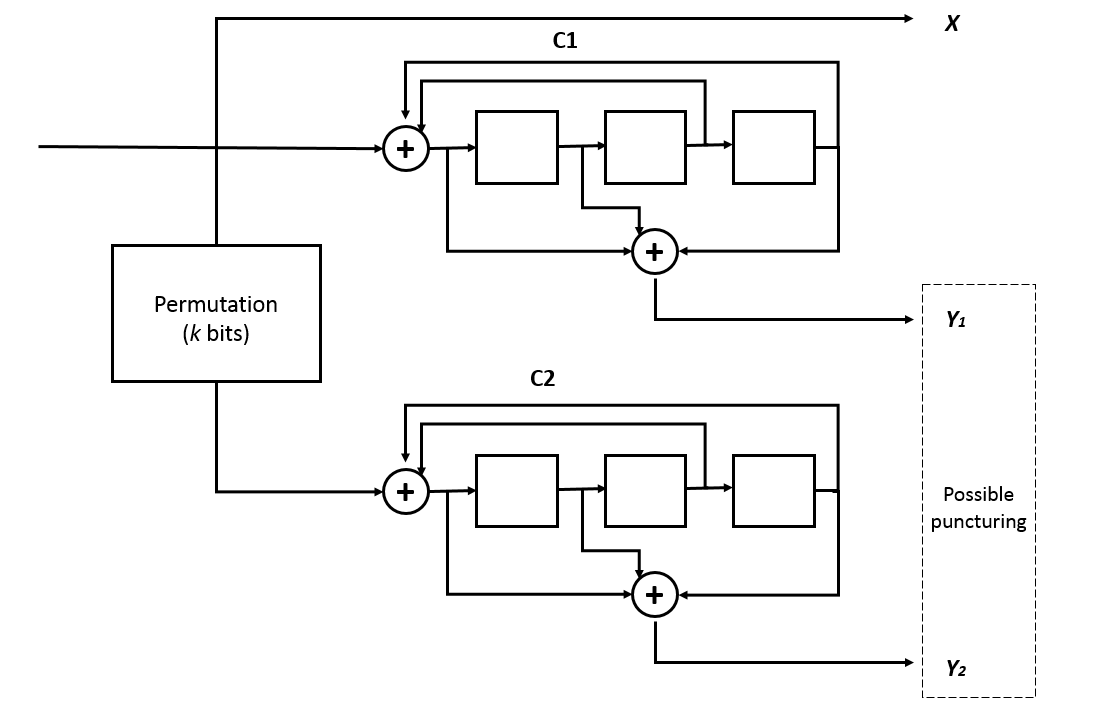

Some sort of parallel Hamming code would use 8 nibbles for every 64 nibble. That's too much latency. Reed-Solomon would be worse. Hopefully a flavour of Viterbi or Treillis (TCM) could work. Not sure if Turbo-Codes, LDPC or similar could be practical.

5-bit nibbles open the door for some trickery in GF(31), and 3-bit nibbles let us play in GF(7).

But in the end FEC/ECC buys us some margin, maybe a 2× or 3× fewer retransmits until things really break down, at the cost of

- Less bandwidth (The fewer retransmits are compounded by the extra bit overhead)

- More latency (the ECC requires another buffer)

- More circuits (more memory, more complexity)

The other fun parts are

- The bandwidth loss of FEC would be equivalent to reducing the transmit rate, which would also reduce the error rate (not the same ratio but still)

- Low bandwidth loss from ECC would require longer buffers, which in turn increases latency and reduce retransmit rate

=> The gain-cost ratio of FEC is not great! A simpler and almost equivalent method would be

- Adjusting / Slowing down the clock frequency (dynamic scaling)

- Reducing the effective bitrate by switching the GCR table

But errors occur and the retransmit algo might not be enough in the cases that interest us. A light touch of FEC is good to detect when things are about to get bad and still work at a decent performance. But as noted above, a "light" (low overhead) FEC requires long buffers and gets in the way of fast retransmission.

The gPEAC18 descrambler has a detection latency of about 8 words (128 bits) and Hamming SECDED can correct 2 bit errors at most in this timeframe. That's not much and the recovered data risks being smushed and destroyed even more, in case of failure, which would do the same "error amplification" work as GrayPar. I don't know yet how much correction is possible in about 128 bits...

Anyway https://arxiv.org/pdf/cs/0504020v2 reminds use that block codes are less efficient than convolutional codes.

I had been trying to understand why in practice convolutional codes were generally superior

to block codes, so I studied Andy’s paper with great interest. I realized that the path-merging

property of convolutional codes could be depicted in what I called a trellis diagram, to contrast

with the then-conventional tree diagram used in the analysis of sequential decoding. It was then

only a small step to see that the Viterbi algorithm was an exact recursive algorithm for finding

the shortest path through a trellis, and thus was actually an optimum trellis decoder. I believe

that at that point I called Andy, and told him that he had been too modest when he asserted

that the VA was “asymptotically optimum.”

.

Now, let's have another look at Wikipedia:

Even simpler!

.

Going up in the page, we find

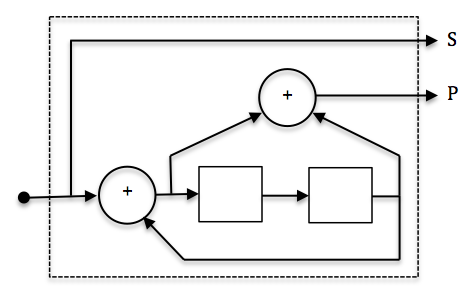

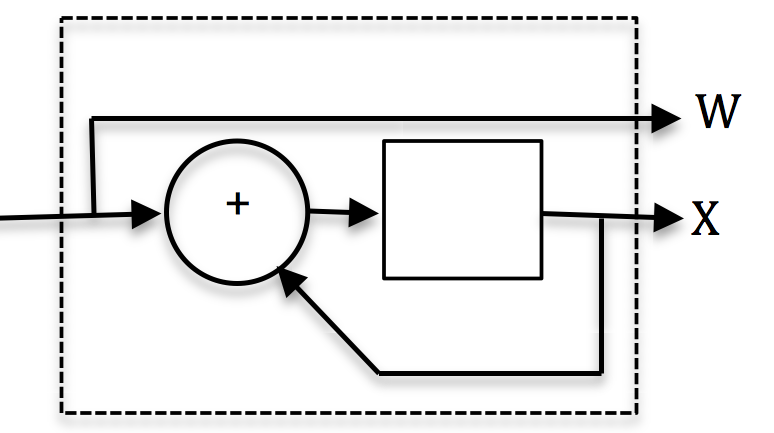

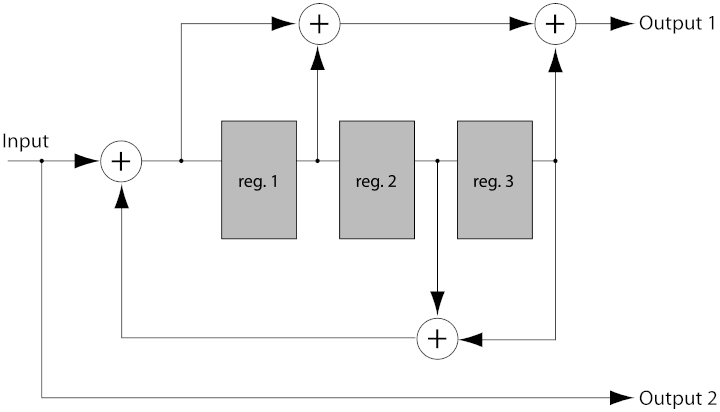

The example encoder is systematic because the input data is also used in the output symbols (Output 2). Codes with output symbols that do not include the input data are called non-systematic.

Recursive codes are typically systematic and, conversely, non-recursive codes are typically non-systematic. It isn't a strict requirement, but a common practice.

The example encoder in Img. 2. is an 8-state encoder because the 3 registers will create 8 possible encoder states (23). A corresponding decoder trellis will typically use 8 states as well.

Recursive systematic convolutional (RSC) codes have become more popular due to their use in Turbo Codes. Recursive systematic codes are also referred to as pseudo-systematic codes.

.

And we want to use a systematic code!

.

Why and what this all means: the input stream is copied directly, and at regular interval a "parity" is interleaved. This parity could be at a reduced rate ("punctured" as they say, or I prefer "decimated" to follow wavelet terminology) to control the overhead (depending on the line SNR).

This means that the latency is in fact quite low : just take the relevant bits/trits/nibbles/... out of the stream, while the check data is percolating through the pseudo-LFSR.

Thus a convolutional or Turbo Code can be in fact used, at varying levels of overhead, since the data is immediately available, but there must be some sort of FIFO that can be "scrubbed" when an error is detected.

Since this works at the trit level, the error is available much sooner than if it was further down the pipeline and since the trits are immediate representations of the line level, there is no loss or spread of data due to 3B2T conversion.

The 3B2T conversion itself can serve as hint for the decoder that something is wrong. Now I have to find out how to decode this and do some Viterbi magic...

But this will be a job for #miniPHY.

.

Yann Guidon / YGDES

Yann Guidon / YGDES

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.