The keen-eyed among you may realize that I didn't actually make anything yet that does something at 1 Hz, I just made a fancy counter. At an average rate of 73.80 counts/second, how do you even divide that into equal seconds? My answer comes in how I scale the counts.

I don't just do seconds = count * 73.80, instead I use integer math, and use the full calibration vales I have:

int64_t count = 0; //increments from ISR

int64_t start_unix = 1753493295; //unix timestamp of the start date and time

#define calibration_count 2330274101

#define calibration_seconds 31574468

loop(){

int64_t elapsed_seconds = count * calibration_seconds;

elapsed_seconds /= calibration_count;

int64_t current_time = start_unix + elapsed_seconds;

log(current_time);

}

The output here is a unix timestamp in seconds, with no errors from floating point math. To get the seconds, I just keep looping and watch for the current_time value to change. I normally just log this value and display it on the LCD, but for more fun, I also tick a mechanical clock movement forward one second.

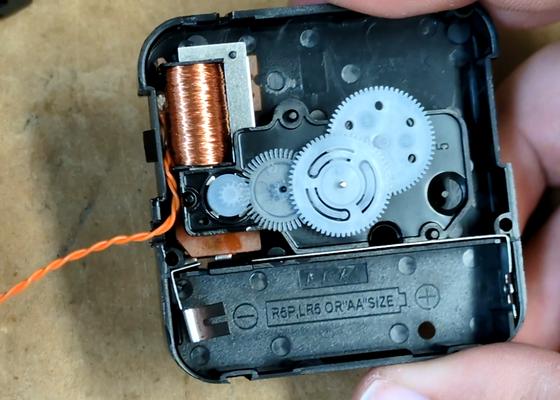

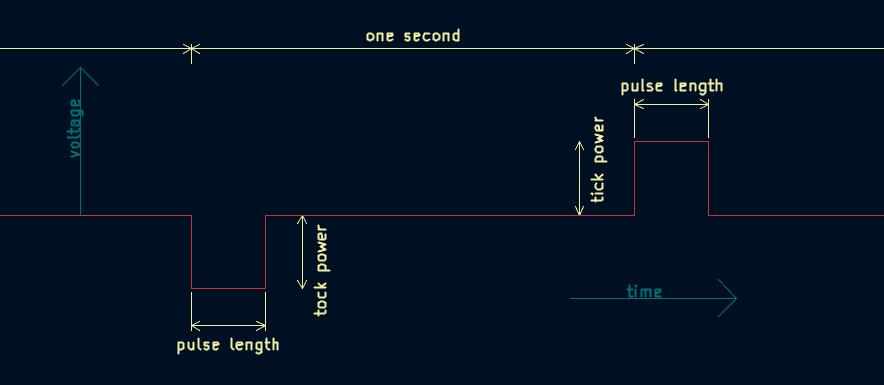

The motor inside every one of these cheap quartz clock movements is called a Lavet motor. It's a type of single-phase stepper motor which has special magnetics so that it only moves in one direction. To drive one, you send the motor coil a signal like this:

Being so low power, you don't need an external H-bridge to drive the coil, two Pico pins (with a 100 ohm current limiting resistor) are enough. Set one high and one low to drive it one way, both low to send no power and low-high to go the other way.

The only hard part was trying to find the correct value of voltage and pulse length to make the motor run evenly. With too much power or too long of a pulse, the motor will overshoot where it's supposed to go and won't tick at all. Too little, and there won't be enough power to move it.

When I say "voltage" on my diagram above, I really mean PWM duty cycle. For some reason, this took the longest to figure out, though it should have been obvious: the clock motor runs fine at about a volt, and the Pico runs at 3.3V. So a duty cycle of about 33% was what was needed. I even replaced the first clock motor I was using, which never worked well, only to see the same issues in a brand new one before figuring out to turn down the PWM.

For the length of the pulse, I found 50ms to work pretty well. This is too short of a time to be derived from the geiger counts, so I used the internal millis() timer for it. But the decision for when to send each pulse is still determined by when the scaled integer seconds count from the geigers increments, so the clock is still radiation controlled.

Later, I realized that the pulse time in the real clock is likely a power-of-2 fraction of a second, probably 31.25 or 62.5ms, since all these clock movements derive the 1Hz motion from a 32768 Hz crystal through a series of divide-by-2 flip flops.

So, how well does it work? See for yourself:

It does tick a little unevenly, not as much as a Vetinari Clock, but it's apparent if you pay close attention. Since my own measurements of the rate say that the typical counts/second doesn't often vary by more than a few percent in any given second, the unevenness here is probably just a result of the integer math. It remids me of Aliasing in graphics, but since I just have to take the seconds as they come I'm not sure what I can do about it.

If you're wondering about the "geiger counter noise" that it makes in the video, this is just something I do when the clock is at the top of the hour. Cookoo clocks have a bird that comes out, and digital watches can beep on the hour. It's just a reminder that the experiment is still going. The ISR is allowed to directly toggle a pin which has a speaker attached, so the sound you hear is clicking from the actual geiger counter. Of course, since the clock drifts so much throughout the year, you sometimes hear it on the half hour, or really at any time. In the above video, I didn't have the minute hand quite aligned properly with the top of the hour.

Why is there a zero at the top of the clock instead of 12?

Only because you asked! I'm not sure why everyone seem to call "0" as "12" when it comes to clocks. Does it really make sense for 12am to come before 11am? Any child can point this out, but apparently our "wrong" version is the one everyone uses. Every other gauge or dial starts at zero, except for clocks for some reason. I've patched this obvious bug in mine, we just need to wait for the admins to merge these changes into the mainline.

alnwlsn

alnwlsn

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.