-

Data General Nova computer sound analysed

02/25/2025 at 21:15 • 0 commentsUsing a so-called bat detector, a machine to make ultrasound audible, I have looked and listened at the sound of the Nova 1210 computer during fast CT reconstruction to locate the origin of the chirping noise. Enjoy the video!

-

Optimising CT reconstruction on 52 years old computer

02/19/2025 at 20:48 • 0 commentsAs shown in the previous page, CT reconstruction works and I think it is quite fast even though the reconstructed slice is only 80x80 pixels as on the original EMI CT scanner.

The core of the reconstruction algorithm is to take the array of projection data and stretch it out over rows of the CT slice. By modifying the shift and pitch of the stretch row by row the effect is a straight backprojection of the projection data, i.e., a single point becomes a line in a preset arbitary direction.

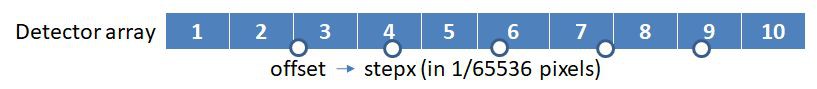

However, pixels of the output data will not land exactly on pixels of the input data (circles).

![]()

I.e., the pixel address is not an integer number. The Nova is 16 bits, so it is reasonable to use 32 bits fixed point numbers and use give the pitch (stepx) in 1/65536 of a pixel.

But the Nova has only four registers, two of which are this needed to maintain the subpixel address. If we have the step in register 2 and 3 and the subpixel address in register 0 and 1 we have used all registers!.

This is the code to step. Because Nova has no add with carry a SZC (Skip zero carry) is used to transfer the carry by incrementing register 1.

ADD 3 0 CZ SZC

INC 1 1

ADD 2 1But now we need to get the projection pixel, and add it to a pixel in the slice row. There are not enough registers. I first dealt with this by using memory for most variables (function GSTRETCHADD):

LDA 1 AC3 // get projection data

LDA 2 IND autoinc.target

ADD 2 1

LDA 2 autoinc.target

STA 1 AC2

LDA 1 stepx

LDA 2 stepx1

ADD 1 0 CZ SZC

INC 3 3

ADD 2 3

DSZ variable.counter

JMP GSTRETCHADD1But a register instruction takes only one cycle, while a memory instruction uses two cycles (3 if using indirection). This loop therefore uses 20 cycles. A variable with octal address 20 is used as its autoincrements when addressing indirect. But we need both read and write with a single increment so more instructions are needed.

We can improve on this as follows as shown in GSTRETCHADDFAST - in step 1 (macro GS1) use 5 cycles to calculate the subpixel address while having the step in registers 2 and 3, and store the result:

ADD 3 0 CZ SZC

INC 1 1

ADD 2 1

STA 1 tempand then - in step 2 (macro GS2) use 8 cycles to add the inpout data pointed to by temp to the slice pixel pointed by AC2.

LDA 1 IND temp

LDA 3 AC2

ADD 1 3

STA 3 AC2These steps take only 13 cycles in toal. However, setting the required registers between steps adds 18 cycles. So 31 cycles in total. That is slower. The trick is therefore not to process one pixel at a time but doing 16 pixels at once by unrolling the loop. Then the 18 cycles overhead are shared by 16 pixels and the total loop requires a bit over 14 cycles per pixel. A speedup of 30%.

That was quite technical! If the assembly code looks strange to you, it is because it is assembled by my own written assembler in Lua. In lua_assembler\NovaReconstructor.lua you find the reconstruction code, file lua_assembler\telnet_nova.lua contains the assembler.

-

See the Data General Nova in action!

02/16/2025 at 19:23 • 3 commentsI just made and published a video of my Nova computer in action. I hope you enjoy it.

-

52 year old computer performs fast CT reconstruction

02/15/2025 at 22:08 • 0 commentsI have previously reported a simulator of a Data General 1210 Nova computer. Last week I gave an invited lecture at the British Society for the History of Radiology and I started with a description of the first CT scanner as designed by Hounsfield around 1970. The clinical system, released in 1973 contains a Data General Nova computer.

I personally first encountered a Data General Nova computer when I sneaked into the 'The Instrument' technology fair in the Amsterdam convention center in 1974. I bought a Nova 1210 computer on Ebay in 2017 and have equiped it with a self-built front panel, as my computer was embedded and did not have one. This panel is controlled by a Teensy board, that can very quickly exchange information with the original Nova computer, as if it toggling the front panel switches thousands of times per second. I wanted to demonstrate CT reconstruction on this computer so this year I have added a small 320x240 pixel LCD display with SPI connection. The latter is controlled by the Teensy in response to normally unused HALT instructions of the NOVA. Similar instructions read a sinogram from the Teensy flash storage.The core algorithm for CT reconstruction is backprojection, that entails drawing each line between the X-ray source and detector, for all angles of acquisition. This might seem like a time consuming operation but already in the first CT scanner it was considered that the process could be described as a linear mapping of image rows to the detector array. To reconstruct a 80x80 image (the original size of the CT slices in the original EMI CT scanner), 1.2 million pixel mappings must be performed. The trigonimetric functions are stored in a lookup table. No multiplications are required, which is a good thing as my computer does not have a multiplier option, one software multiplication takes about 100 microseconds.

The end result is an efficient backprojection. However, the converging lines result in a wash around the center of the intersecting lines. If you do this for a entire slice of head, the image becomes very blurred. For that reason the input signal must be filtered so counteract the blurring: filtered backprojection. My latest code can do an entire slice reconstruction in 35 seconds, quite a bit faster than the reported 5 minutes reconstruction time on the first CT scanner.

The entire story, including a live demo of the CT reconstruction on the Nova can be found on the BSHR web site: Marcel's lecture on the history of digital imaging.![]()

![]()

Straight backprojection of a single point. Straight backprojection of a CT slice.

The core algorithm for CT reconstruction is backprojection, that entails drawing each line between the X-ray source and detector, for all angles of acquisition. This might seem like a time consuming operation but already in the first CT scanner it was considered that the process could be described as a linear mapping of image rows to the detector array. To reconstruct a 80x80 image (the original size of the CT slices in the original EMI CT scanner), 1.2 million pixel mappings must be performed. The trigonimetric functions are stored in a lookup table. No multiplications are required, which is a good thing as my computer does not have a multiplier option, one software multiplication takes about 100 microseconds.

The core algorithm for CT reconstruction is backprojection, that entails drawing each line between the X-ray source and detector, for all angles of acquisition. This might seem like a time consuming operation but already in the first CT scanner it was considered that the process could be described as a linear mapping of image rows to the detector array. To reconstruct a 80x80 image (the original size of the CT slices in the original EMI CT scanner), 1.2 million pixel mappings must be performed. The trigonimetric functions are stored in a lookup table. No multiplications are required, which is a good thing as my computer does not have a multiplier option, one software multiplication takes about 100 microseconds. The end result is an efficient backprojection. However, the converging lines result in a wash around the center of the intersecting lines. If you do this for a entire slice of head, the image becomes very blurred. For that reason the input signal must be filtered so counteract the blurring: filtered backprojection. My latest code can do an entire slice reconstruction in 35 seconds, quite a bit faster than the reported 5 minutes reconstruction time on the first CT scanner.

The end result is an efficient backprojection. However, the converging lines result in a wash around the center of the intersecting lines. If you do this for a entire slice of head, the image becomes very blurred. For that reason the input signal must be filtered so counteract the blurring: filtered backprojection. My latest code can do an entire slice reconstruction in 35 seconds, quite a bit faster than the reported 5 minutes reconstruction time on the first CT scanner.