The mechanical joints necessary for this project must fulfil several requirements of the umbrella project.

Namely:

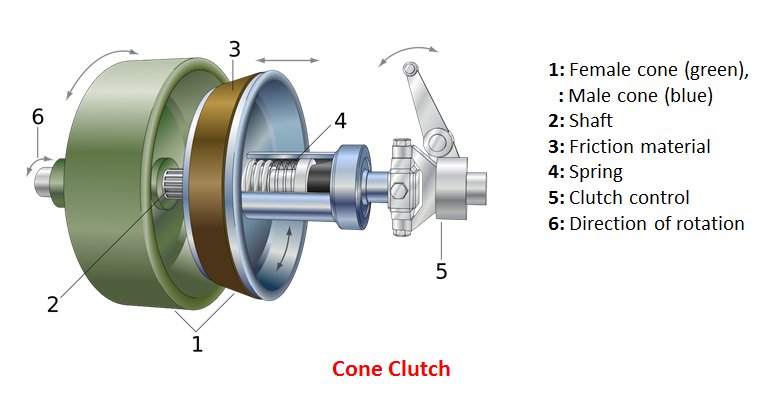

- Rotate in 1, 2 or 3 axes

- Only move in those axes, no wobble

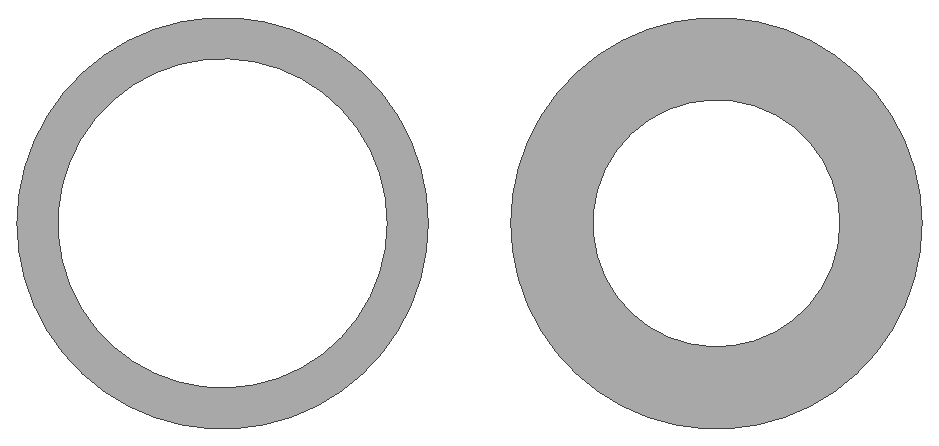

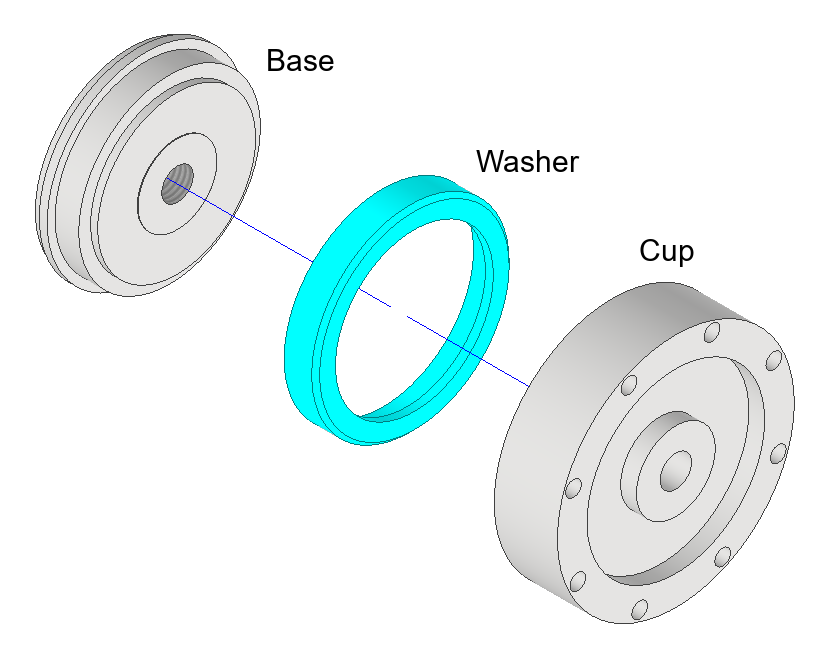

- Lockable

- Free-moving to fully locked in 1 small motion

- Using only 1 hand

- Range of mounting options

- Multiple threaded holes

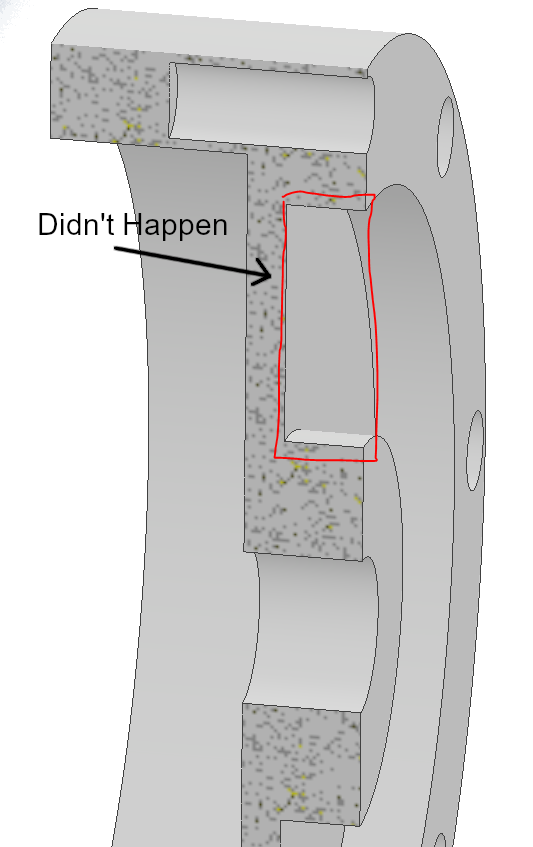

- OR counter-bored holes to allow mounting without access to the back of a panel/wall

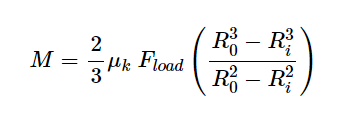

- Friction

- Metal to plastic contact for the sliding elements to prevent binding or galling.

- Cheap

- Less than £20 in materials and accessories

- Time spent is less relevant at this stage

With this list of requirements in mind, I will be designing and making a series of joints and eventually assembling a long arm for the shed.

Greg Duckworth

Greg Duckworth

FiveseveN

FiveseveN

agp.cooper

agp.cooper

Zoé

Zoé