There is something radical about making and using your own scientific instruments. The structure of scientific inquiry has coalesced around a model that is, in general, both expensive and exclusive. This centralizes knowledge production within a circle of individuals, organizations, and institutions which rarely reflects the breadth of identities, experiences, and ways of knowing of those most directly connected to the places being explored.

By building your own instruments to study and understand the natural world, by taking ownership over the tools of scientific inquiry, you contribute to expanding that circle of knowledge production. A scientist who can make their own instruments is not beholden to the cycles of funding and access that pervade formal, institutional inquiry. A researcher who can build and repair their own equipment is not dependent on the ever-changing wind of academic sentiment to decide what is and is not worthy of study. A community leader who has the tools to create their own data does not have to wait for institutions to take notice of an emerging crisis before taking action.

You don’t need to ask for permission to understand your world.

Nowhere is this inequality of access more pronounced than in the ocean sciences, where all but a few entities have the capital to mount major oceanographic research campaigns. Even localized coastal research can be stymied by the need for vessels, equipment, and instruments, access to which is often controlled by research institutions. As the need to understand the dramatic changes happening both at the surface and beneath the waves accelerates, barriers to access that precludes the participation of ocean stakeholders further erode our potential to understand, anticipate, and mitigate those changes.

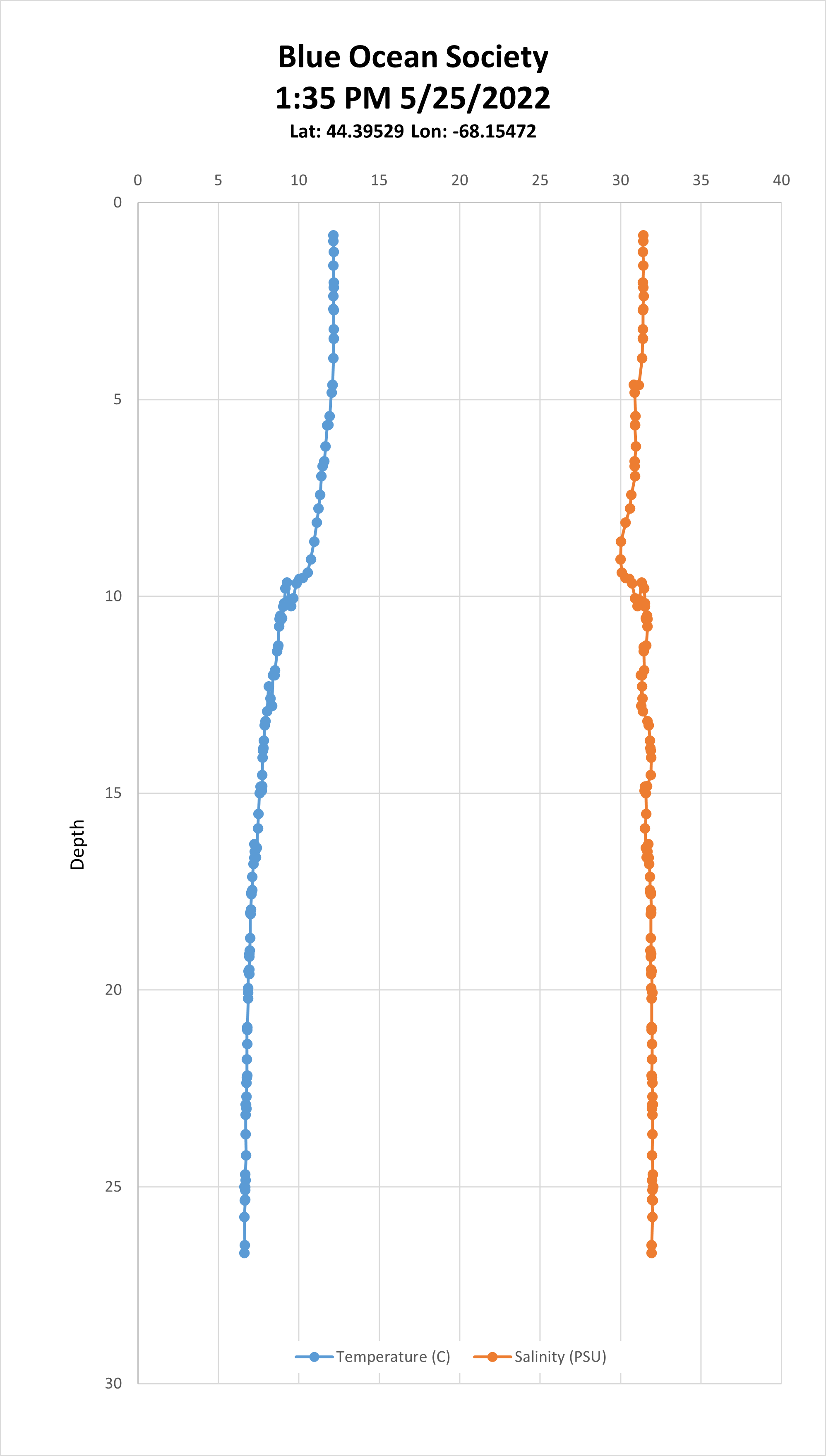

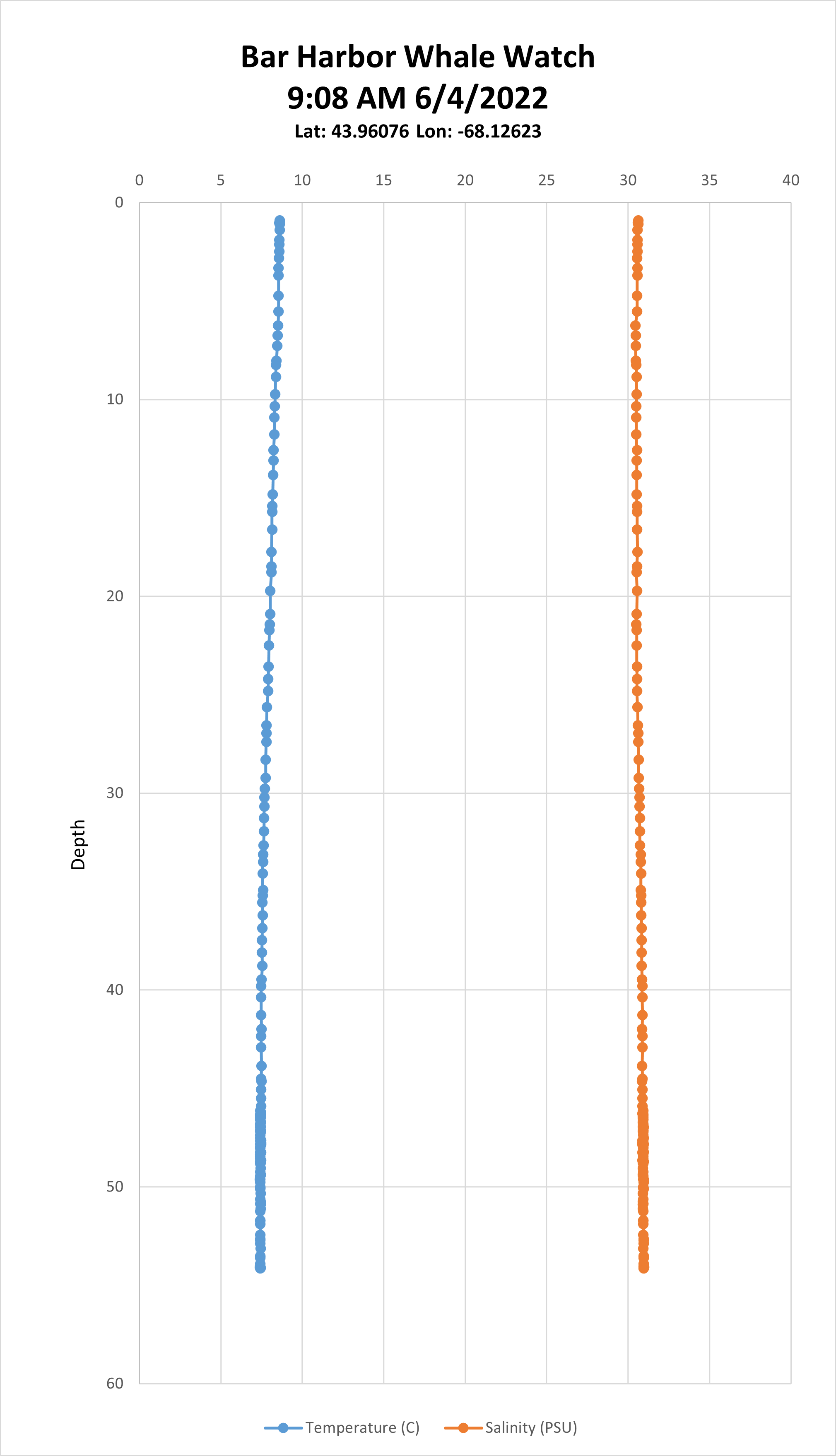

The ocean belongs to everyone. The tools to study the ocean should be accessible to anyone with the curiosity and motivation to pursue that inquiry. Chief among these tools is the workhorse of oceanography, the CTD, an instrument that measures salinity, temperature, and depth. By these characteristics, scientists can begin to unlock ocean patterns hidden beneath the sea's surface.

CTDs come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and applications. Most oceanographic research vessels have a CTD connected to a rosette platform, which houses other instruments and collects water samples in parallel with real-time data. CTDs are also commonly attached to fixed moorings, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), remote-operated vehicles (ROVs), and, on occasion, marine animals. But commercial CTDs are expensive, with the even most affordable models costing several thousand dollars. For near-shore oceanographic research on the continental shelf, where the water depth rarely exceeds 200 meters, this cost can be prohibitive. The expense of the CTD is a barrier-to-entry for formal and informal researchers working with limited budgets, including scientists from low- and middle-income countries and small island states, as well as citizen oceanographers, environmental educators, conservation and management practitioners, and students of all levels interested in understanding their local coasts and waterways.

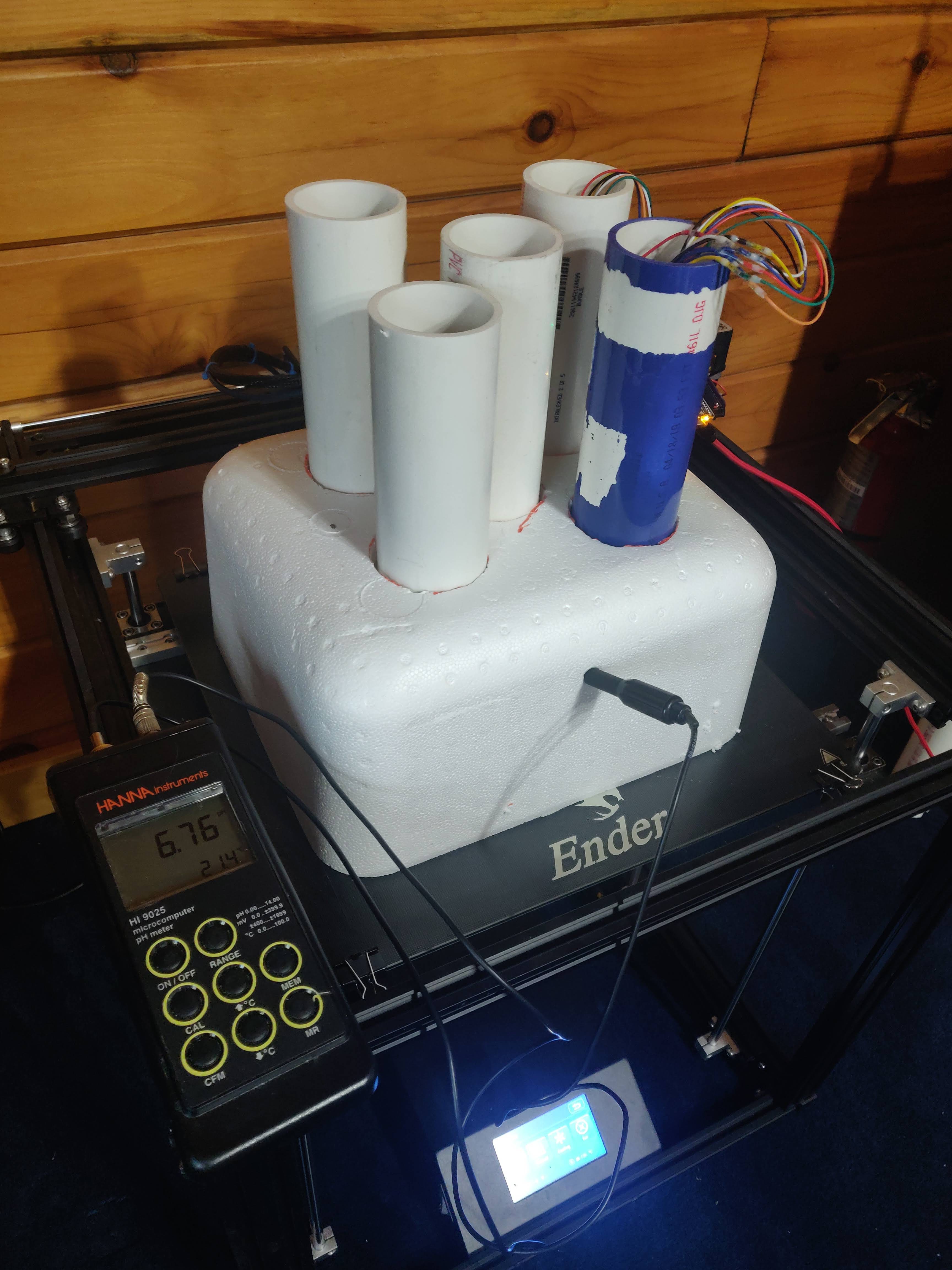

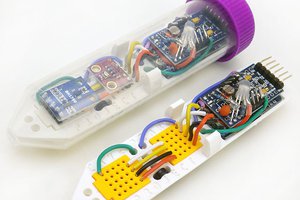

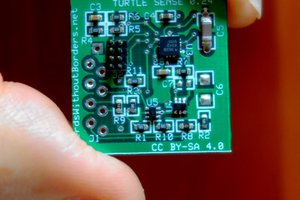

The OpenCTD is a low-cost, open-source CTD designed intentionally for budget-restricted scientists, educators, and researchers working in nearshore coastal ecosystems, where entire research projects can be conducted for less than the cost of a commercial CTD. It was developed by a core team of marine ecologists in collaboration with a distributed community of scientists, engineers, makers, and conservation practitioners. It is assembled from components commonly available at large hardware stores or through major online retailers. An Arduino-based microcontroller controls a battery of sensors sealed within a PVC pipe. Power is provided by a standard 3.7V lithium polymer battery and data are stored in a tab-delimited text file accessed via SD card. All OpenCTD software is released open...

Read more » andrew.david.thaler

andrew.david.thaler.jpg)

Ed Mallon

Ed Mallon

Samuel Wantman

Samuel Wantman

hornig

hornig