...and tough too!

In the previous entry about contacting local scale model builders to ask if they might appreciate an accessible little CNC machine, I mentioned a couple tries at making a "trail board" for a Midwest Model Shipwrights member.

People have been making scaled-down models of inconveniently large things for a long time ... and I've abandoned hope of summarizing that in a sentence. Making detailed wooden models of wooden ships stands a little aside from the model-making mainstream as we approach the 21st mid-century AD, but the venerable practice persists and practitioners gather nearby.

Wood has grain. Scaling down wooden parts has the effect of scaling up the wood's grain. Very fine grain woods mitigate that with good success well established[1]. But trying to capture finer detail at smaller scale eventually turns into trying to carve a tea set from a stack of sewer pipe.

From last time:

- I wrote about FR2 exceeding expectations as a machinable material not entirely completely unrelated to wood but with essentially no grain. "FR2" is an imprecise term for the brown resin-saturated paper board used for the cheapest, simplest circuit boards.[2] Similar material is available by other names. Contrast with FR4 which is glass fiber+epoxy and hostile stuff to work with. I'm thinking this paper+phenolic stuff looks promising for compatibility with wood model construction, but that remains untested by actual model builders -- that I know of. But maybe I'm just the last guy to get the clue. Some "phenolic paper" material is advertised for "enhanced" or "finest" machinability. "FR" = flame retardant.

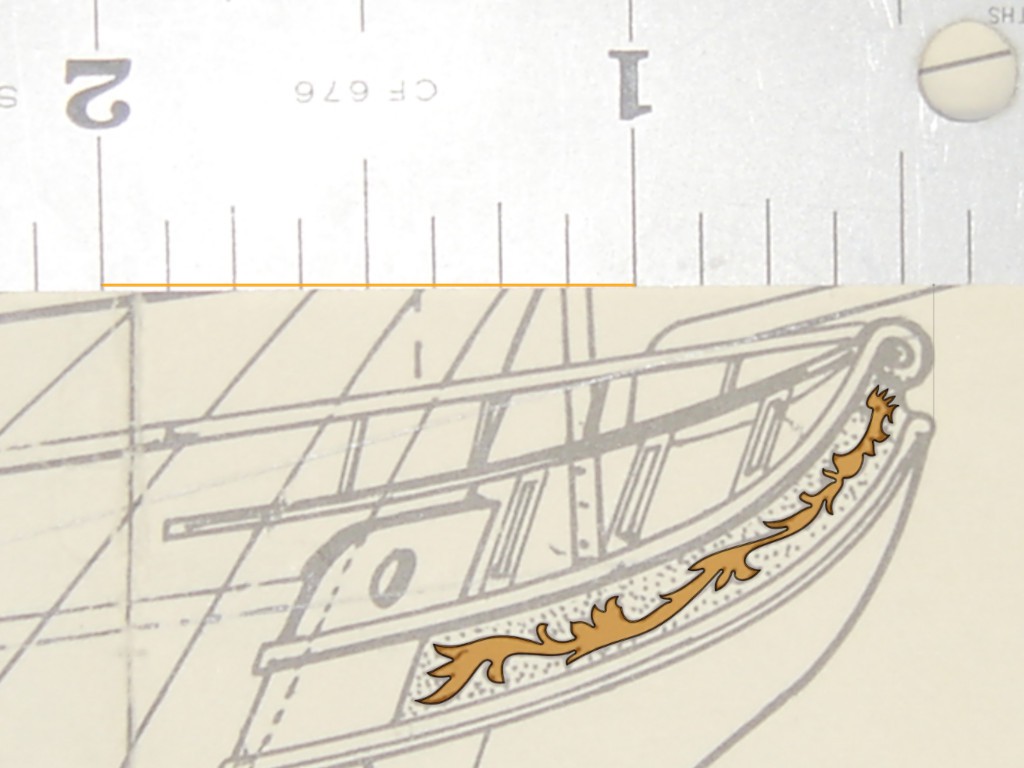

- I had started off in the wrong direction with the first couple of whacks at the "trail board" example. Further information clarifies that what look like scrollwork borders of a flat board appear straight only in profile. The ornamented part is parallel with the mid-plane so it can be taken directly from the drawing. And the builder already has the structure and only needs the decoration.

So, back to the drawing board.

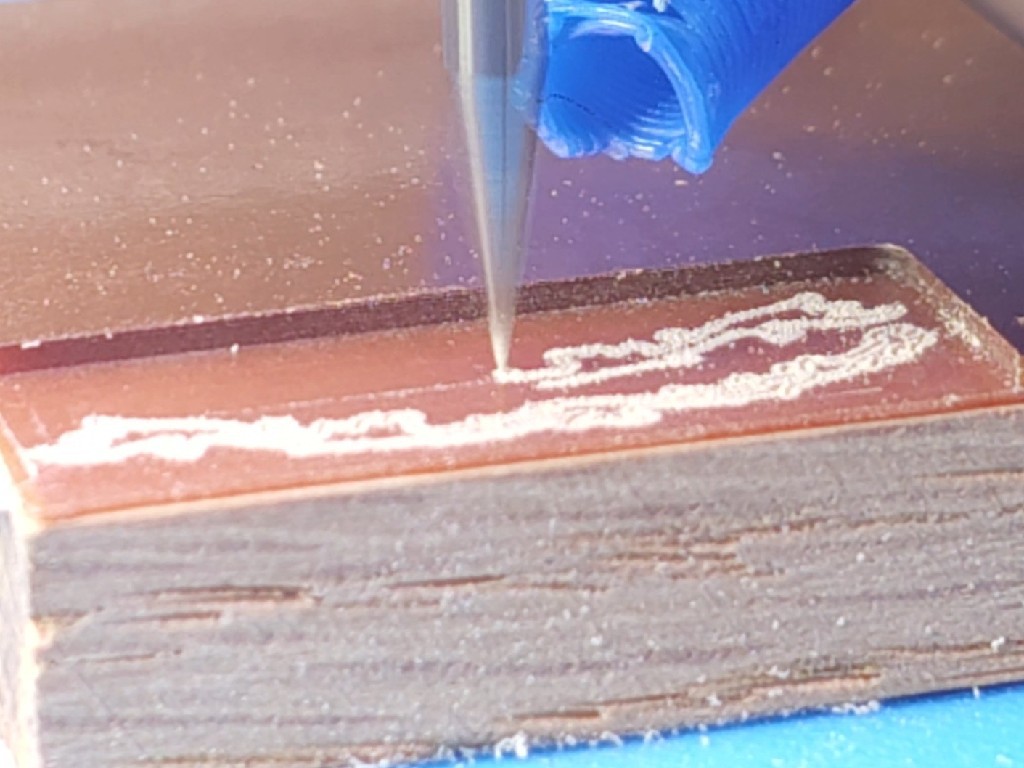

Then milled a patch of FR2 down to 0.3 mm thick (or so I thought, but it came out more like 0.34mm -- dunno why) and from that cut out a mirrored pair of figures using a 20°, 0.1mm Vbit. I didn't feel like testing how deep it could cut without breaking the tip or deflecting when I really wanted the best narrow cut and sharp inside corners, so I ran six passes at very conservative ~0.05mm steps down ("~" because a little more to match four Z motor half-steps). I expected that to cut through or very nearly so. But it didn't. So I ran a few more half-steps down until the bottom of the cut looked different. I was complicating this for myself by trying to cut no deeper than necessary because deeper makes the V cut wider.

When I peeled that up it turned out of that I still hadn't cut through. My current guess is that maybe the glossy surface layer has a different consistency so the top of the bottom skin looks different, but I don't know. In any case, that was initially disappointing. Then I tried sanding the remaining thickness off the uncut side, and that worked quite well.

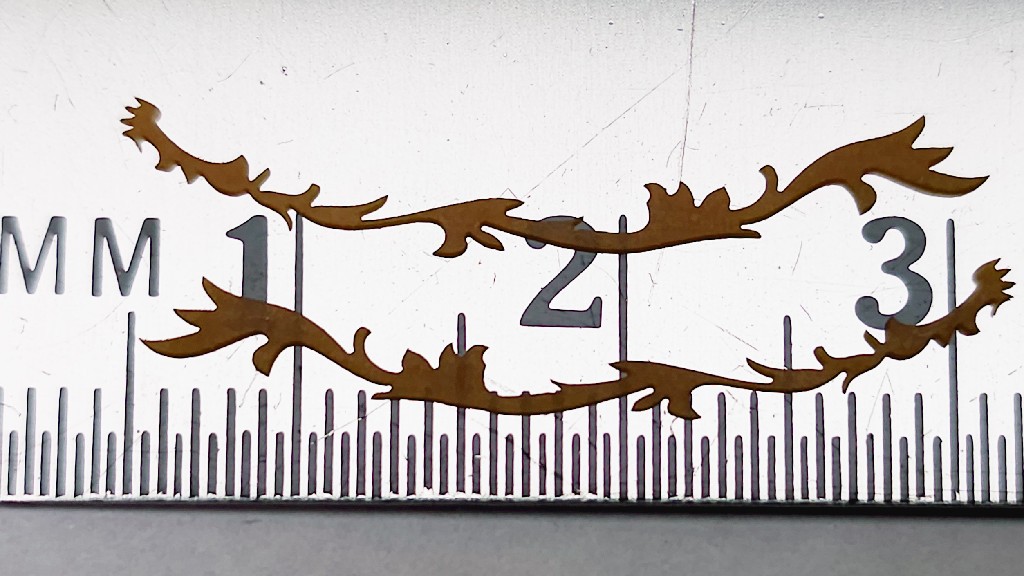

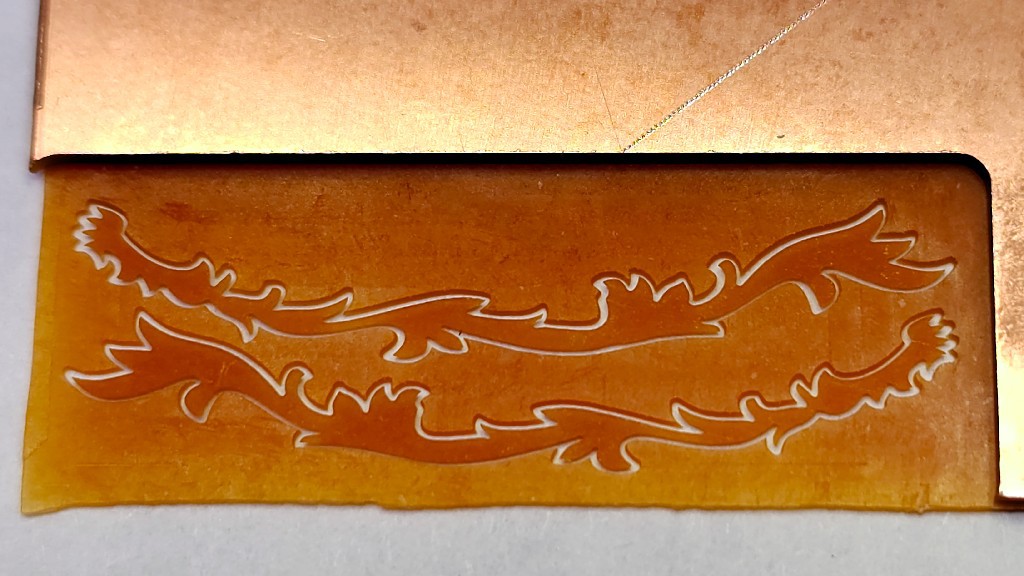

Some beauty shots:

That's a half-millimeter scale. (labeled "MM" in CAPS and numbered by cm. :-/ )

Check out how thin the thin parts are! Earlier I didn't have any great ideas for how to avoid bending that if made from something like brass or styrene, or breaking it if possibly something like that could be cut from boxwood (which I have yet to try). That's where the FR2 works great. Not only is it possible to make those, but also to handle them. They are, of course, fragile. But so far I've been able to handle them "carefully", in the ordinary sense of "careful".

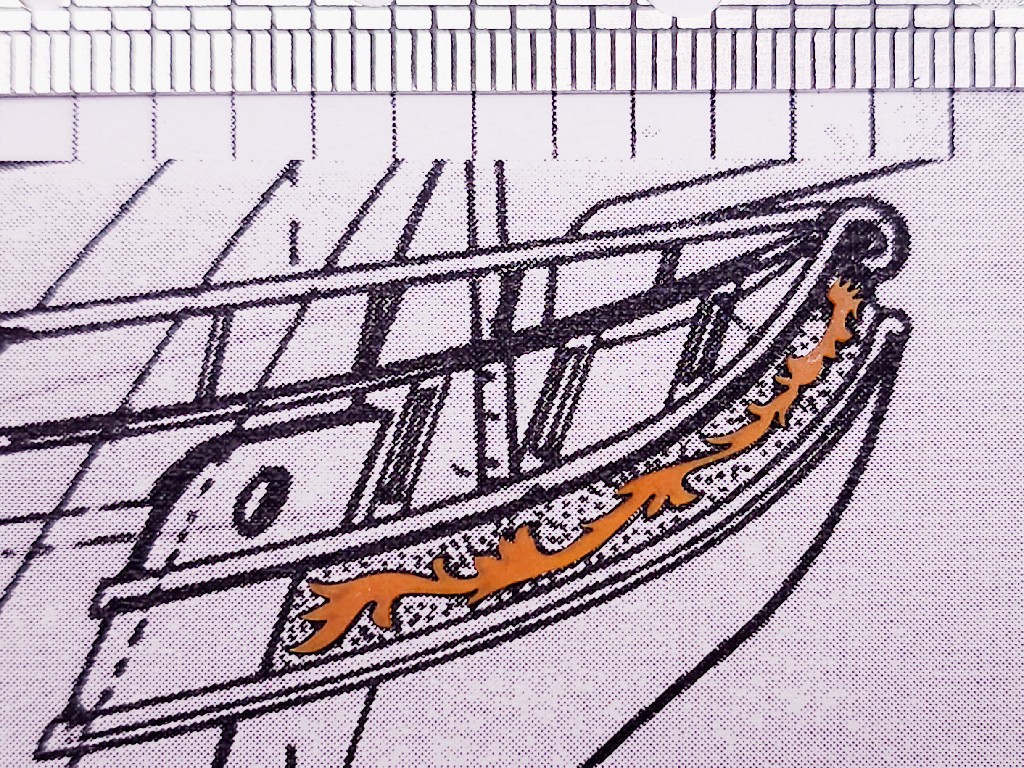

I gather that a chronic challenge / mark of skill among model builders is matching reflected pairs of parts or features like this. To demonstrate the accuracy of match, here are the two parts flipped upside-down and each fit into the hole from which its opposite was cut:

And here's the ̶r̶i̶g̶h̶t̶ ̶s̶i̶d̶e̶ starboard part on a print of the photo of the plan scaled to (nearly) match the printed ruler to a real one:

Now it remains to deliver this back to the builder for a fit check -- both practical and subjective.

A running theme that has kept this project going is exceeding expectations. Again. These two parts are very far beyond anything I had in mind at the start, and still better than I expected even after ratcheting up expectations by lots of steps since then.

=====================8<-----------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Chief among fine grain wood, as far as I know, is the proper species of boxwood grown in favorable conditions. Very much a specialty product and apparently not trivial to "just buy" the good stuff without doing some homework.

I'm sure I'd heard of "boxwood" here and there as a forgettable passing datum. I've never tried to do anything with it (yet -- I've acquired a small sample but haven't had a chance to interact with it). The reason I remember it is because I saw this a few years ago. The link gets some nice pictures but to see the thing you have to go there and make nose-prints on the display case. It's amazing regardless of the material or downer subject. The idea that it was carved in wood is ... cognitively challenging. And a) it's 500 years old, and b) in 500 years it's never been mishandled.

A wider-than-usual digression, but that's what I know about boxwood.

[2] More correctly hyphenated "FR-2". Mostly if anyone says what it is they mention "paper", "phenolic" something, and maybe a random standard related to fire. This was way too hard to find: the real, if nominally obsolete, definition from page 173 of this limited "preview" of NEMA LI 1-1998 (R2011). (<rant>The current version is jealously guarded behind a $551 paywall. What's the deal with secret standards in 2025 when dissemination doesn't require a paper mill?</rant>)

NEMA GRADE FR-2 ... is a laminated material which is constructed from a cellulosic paper combined with a phenolic resin binder. The paper is normally cotton linter or alpha cellulose, but can be manufactured from bleached kraft. The phenolic resin system is flame retardant to a minimum of UL-94 rating of V-1, and is normally plasticized to permit good punching from ambient to slightly elevated temperatures.

Military Specification: MIL-I-24768/25

IEC Specifications: 60893, PF CP 308

Grade FR-2 is used as a flame retardant, room temperature to slightly elevated temperature punching, material for use as mechanical support in electrical applications.[sic] It has good moisture and relatively low dielectric losses under conditions of adverse humidity and temperature.

It looks like the thing that mostly slides under the radar but helps us in this case is "normally plasticized" which I suspect contributes to machinability and toughness. FR-1 definition suggests it's less plasticy at room temperature.

Paul McClay

Paul McClay

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.