Introducing JASPER - Just Another Spectrometer? Not Quite!… Built for Right to Repair

This project started with a simple idea: build an accessible, high-performance VIS-NIR spectrometer that empowers users and supports the right to repair. We're incredibly excited to share our work with the Hackaday community.

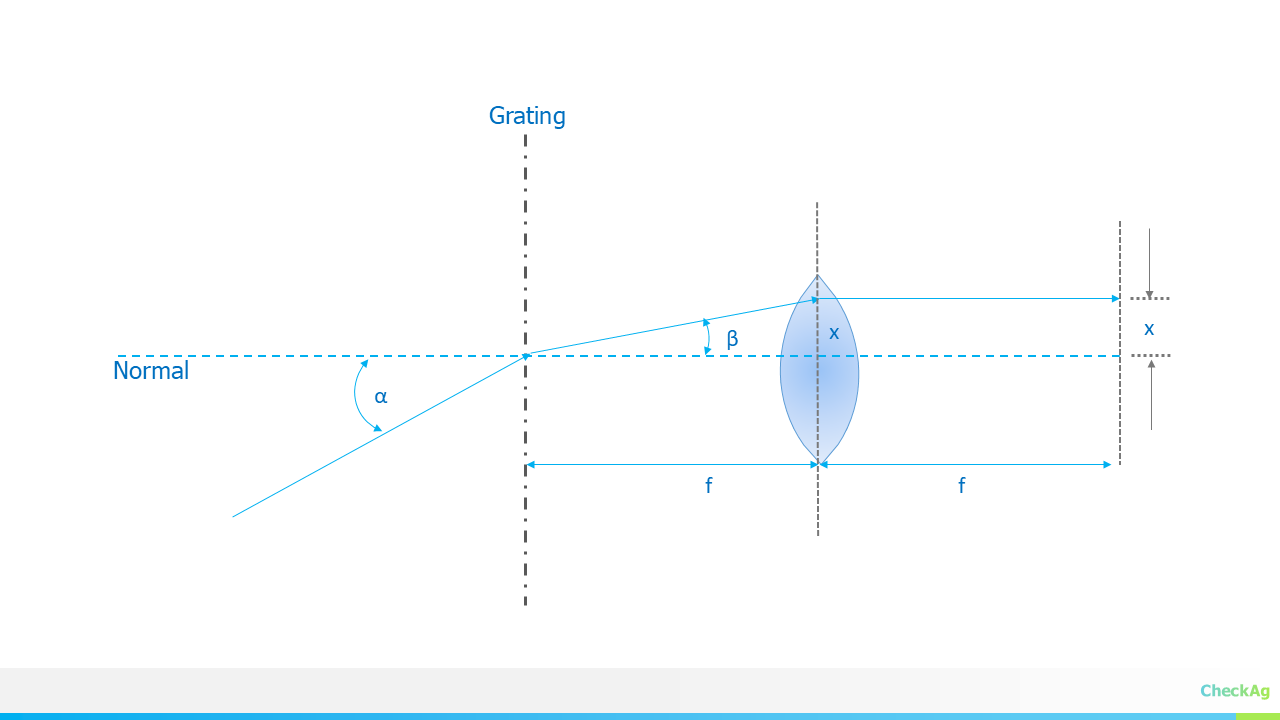

A Hybrid Approach to Spectrometry

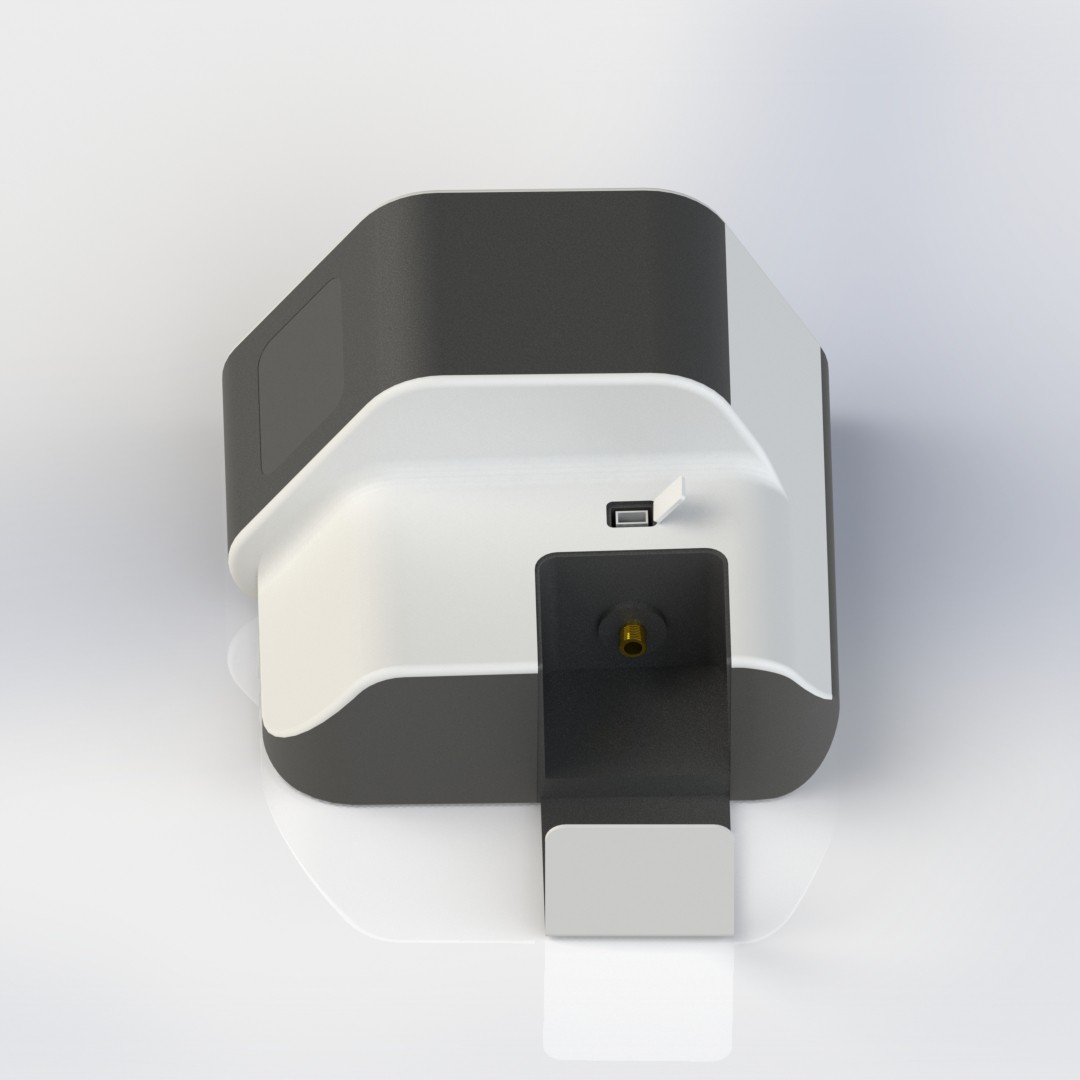

JASPER is designed for flexibility, supporting multiple sampling modes in a single, compact device. Whether you're in the lab or out in the field, JASPER adapts to your needs.

- Cuvette Holder: Perfect for analyzing liquid samples like milk or plant extracts.

- SMA Connector: Connect a fiber optic probe to measure samples directly, such as the surface of a piece of fruit or a plant leaf.

- Accessory Port: This built-in port allows for standalone operation with an integrated tungsten halogen lamp, so you don't need a separate light source.

This hybrid approach allows you to seamlessly switch between lab-grade and field-ready configurations, giving you the best of both worlds with minimal hassle.

Stay tuned for more updates and detailed build instructions! Follow for future updates!!

Tony Francis

Tony Francis