In the precise world of Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, the integrity of the optical path is paramount. Two fundamental optical components often used for beam steering are the plane mirror and the retro-reflector, also known as a corner cube prism. While both serve to redirect light, their operating principles and performance differ dramatically, with a key figure of merit—beam deviation—determining their suitability for the demanding application of an FTIR interferometer.

Beam deviation is the angular change in the direction of a light beam after it is reflected. In an FTIR, a delicate interference pattern is created by combining a beam that has travelled a fixed distance with one from a moving mirror. This requires the beams to remain perfectly aligned and overlapped at the detector. Even a minute beam deviation would cause the return beam to fail to overlap with the static beam, leading to a reduction in the interference signal and, in the worst case, a complete loss of signal, resulting in a distorted or non-existent spectrum.

The Plane Mirror: A Foundation of Reflection

A plane mirror is a simple, flat surface that reflects light according to the law of reflection: the angle of incidence (θi) equals the angle of reflection (θr). This straightforward relationship makes it ideal for basic beam steering or folding the optical path in a fixed optical setup.

The primary disadvantage of a plane mirror is its extreme sensitivity to alignment. Any angular misalignment or tilt (α) of the mirror surface results in a doubling of the beam deviation to 2α. To put this into perspective, for a light beam traveling a meter to a mirror and back, a misalignment of just 0.1∘ would cause the returning beam to shift by over 3.4 millimeters. For the dynamic movement required in an FTIR, this sensitivity makes a plane mirror impractical. The mechanical precision needed to keep a moving mirror perfectly parallel to the beamsplitter is virtually impossible to achieve, causing the return beam to wander and miss the detector entirely.

The Retro-reflector: The Ultimate in Beam Stability

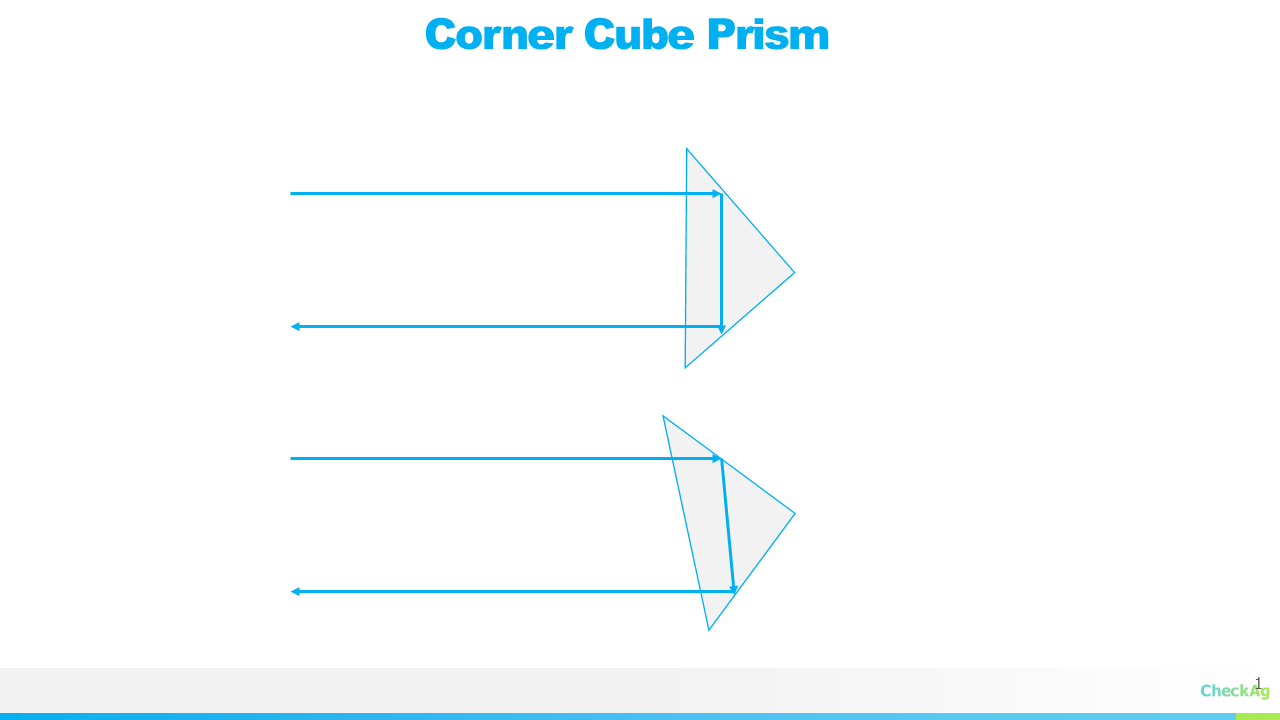

A retro-reflector is an optical component designed to reflect an incident light beam back along a path that is precisely parallel to the incoming beam, regardless of the angle of incidence. The most common type is a corner cube prism, which consists of three mutually perpendicular reflecting surfaces. This ingenious geometry ensures the output beam's direction is always corrected.

The operating principle relies on a series of three sequential reflections. As the incoming ray hits each of the three mutually perpendicular surfaces, its vector components are successively reversed. This triple-reflection geometry ensures the emergent ray is anti-parallel to the incident ray, making the output beam precisely parallel to the input. This property holds true even if the entire prism is slightly tilted or misaligned, as the corrections from the three reflections cancel out the initial misalignment. This allows for a very high tolerance for alignment errors.

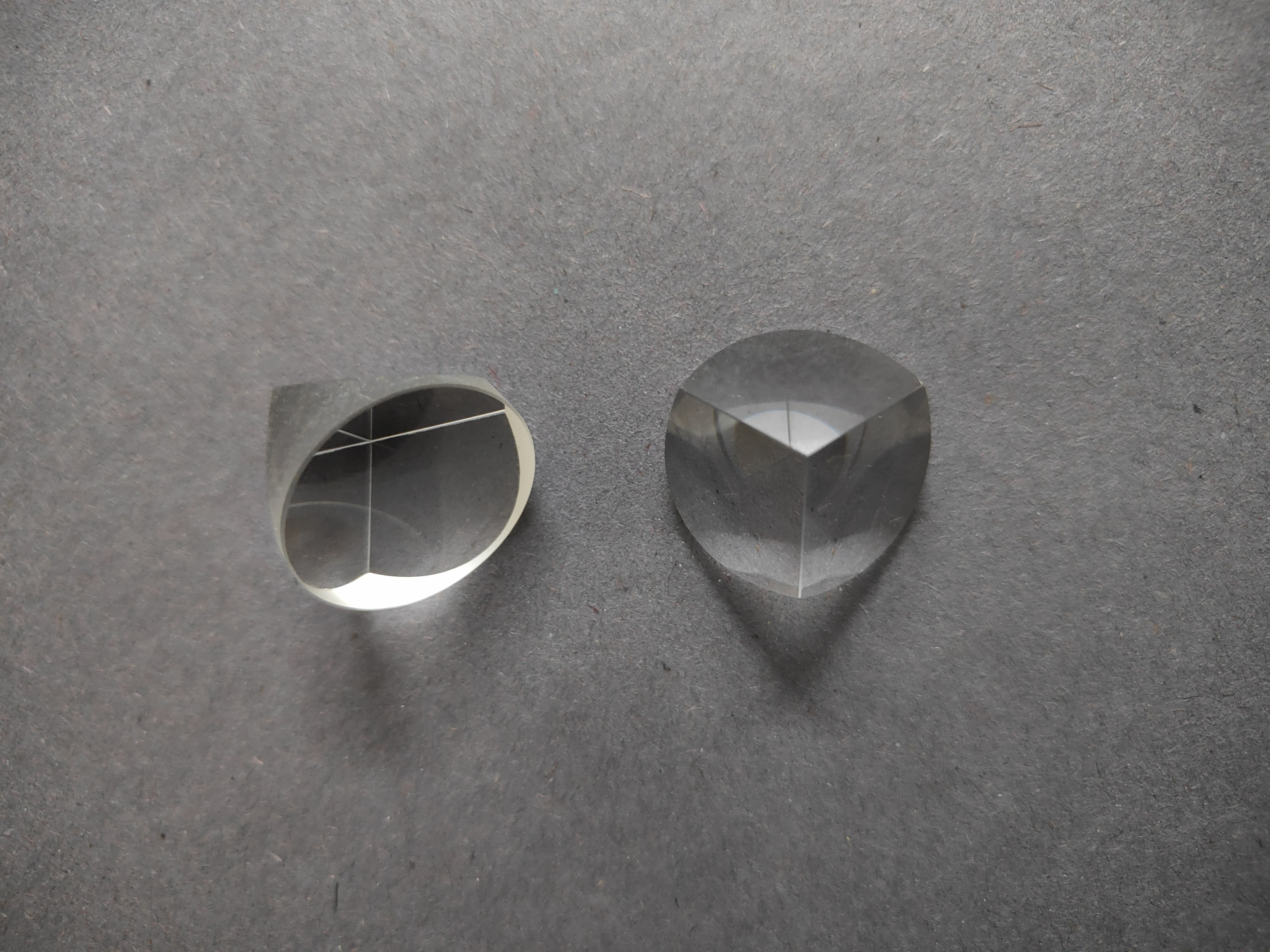

A Note on Retro-reflector Materials

The solid retro-reflector prisms, often made from materials like BK-7 glass, are indeed used for white light interferometry. The reason for this is practical: it is much easier to view and align white light fringes with visible light. For this purpose, a solid prism is a simple and effective choice. However, these prisms are not transparent to infrared (IR) light. Because the light source in an FTIR is in the infrared range, a solid glass prism would simply absorb the beam, making it useless for the spectrometer. For this reason, FTIR instruments rely on hollow retro-reflector mirrors, which are constructed from three flat mirrors arranged in a corner cube configuration. This design provides the same self-correcting optical path without the need for a solid, absorbing material in the beam path.

Comparison and Application in FTIR

The contrast between these two components makes the choice for an FTIR interferometer clear. The moving mirror must maintain perfect parallelism to ensure the recombining beams create a stable interferogram. A plane mirror would require impossible mechanical precision, as the moving stage would have to be perfectly straight and level across its entire range of motion. The retro-reflector, however, can handle the minute mechanical imperfections of the moving stage, automatically correcting the beam's path and ensuring it consistently returns to the beamsplitter. This inherent stability is why retro-reflectors are the standard in modern FTIR instruments, as they enable the robust, continuous-scanning performance needed for accurate and reproducible measurements, even in dynamic or vibration-prone environments.

Tony Francis

Tony Francis

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.