We've all enjoyed the relatively simple beauty of laser interference fringes. Armed with a red or green laser diode and a basic Michelson Interferometer, fringes appear easily because of the laser’s high coherence length. Imperfect optics or slightly misaligned mirrors? No problem—the fringes are often still there!

Our current quest, however, is far more challenging: achieving interference fringes using a broadband white LED.

Coherence is King (and White Light is the Usurper)

Switching to a broadband source fundamentally changes the game. While a laser might have a coherence length measured in meters, a white LED’s is drastically shorter—often just a few micrometers (µm).

This is why the literature is spot-on: for white light fringes to occur, the path length difference between the two arms of the interferometer must be incredibly small. We're talking less than a micrometer of deviation (∆L < 1 µm) near the Zero Path Difference (ZPD) point.

🛠️ The Optics Challenge: From Planar Mirrors to Retroreflectors

Our initial attempts with standard planar mirrors were frustrating. It’s nearly impossible to ensure perfect parallelism and zero deviation with manual alignment and imperfect components. Even slight mirror imperfections, which a highly coherent laser shrugs off, completely destroy the faint white light fringes.

Our breakthrough came with retroreflectors (also known as corner-cube mirrors). These components, commonly found in commercial FTIR systems, inherently return the incoming beam parallel to itself, regardless of the retroreflector’s exact orientation (within limits). This stability proved critical for maintaining the necessary precision, allowing the light from both arms to recombine coherently, thereby addressing the high sensitivity of white light interference to angular alignment.

The Alignment Grind 📐

Perfect alignment is the ultimate hurdle. We’ve had to adopt a multi-step approach:

- Laser Homing: We start by using a visible laser (like the red one) to generate fringes. We track the movement of the fringes as we move the mirror, mapping out the distance and locating the general region of the ZPD.

- The Window & Beamsplitter: The compensation window and beamsplitter arrangement is crucial. To simplify alignment and guarantee parallelism, we’ve sandwiched the two components into a single, tightly enclosed assembly. This ensures that the beamsplitter’s thickness is perfectly compensated by the window, minimizing path errors caused by dispersion.

- The White Light Moment: Only when the laser alignment is near-perfect do we switch to the white LED. The fringe pattern only appears for a minuscule movement of the mirror—literally a few micrometers.

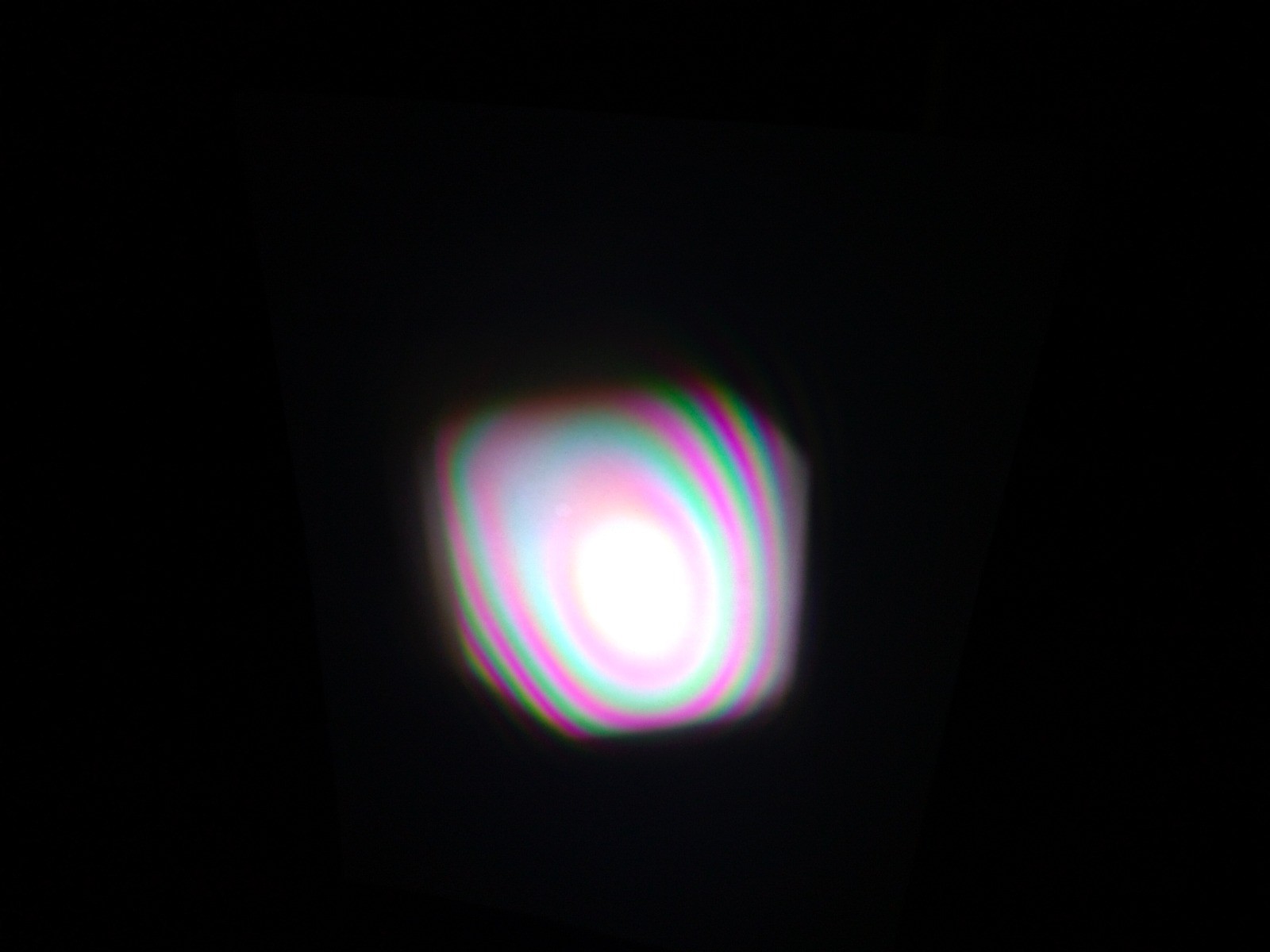

- The Target: We are aiming for perfect circular fringes , which signify that the interferometer is perfectly aligned and the two wavefronts are planar and parallel across the entire beam.

Sometimes, this process takes mere minutes; other times, it's an hours-long battle—truly a needle-in-a-haystack search for the Zero Path Difference.

Looking Ahead to the Invisible: FTIR Challenges

Our end goal is to work in the infrared (IR) spectrum for Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. This presents a new, major problem: we cannot see the IR fringes. We'll have to rely on thermal cameras or sensitive detectors.

In commercial FTIR systems, this is often handled by having a KBr beamsplitter, which is transparent to both visible (white) and IR light. Manufacturers align the ZPD using a visible white light source and then swap the source for the thermal IR emitter, knowing the alignment holds.

But with materials like ZnSe (often required for certain IR ranges), we lose that luxury, as ZnSe is opaque to visible light. We must devise a robust way to achieve perfect alignment and ZPD using only the IR source, or an ingenious external visible alignment reference.

White light interferometry is the core principle behind Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (FTS), which is dominant in the IR (FTIR) and Terahertz range. However, for the visible and UV spectrum, the extreme mechanical precision required to scan a tiny distance for broadband visible light and the computational overhead of the Fourier Transform generally make them less practical than robust grating systems.

You can view the video to see the perfect circular fringes we finally managed to capture using the white light LED. This pattern signifies the interferometer has reached the highest level of alignment and is a must-achieve milestone before we can move on to working with invisible infrared (IR) light.

When we switch to IR, we lose this valuable visual cue and will have to rely entirely on detectors or thermal cameras to "see" the fringes.

Why No White Light Spectrometers?

You might wonder why, given the successful demonstration of white light fringes, we don't see many white light interferometry-based spectrometers on the market.

The reason largely comes down to the maturity and performance of grating-based spectrometers.

- Simplicity and Robustness: Grating systems are mechanically simpler and more robust, without the ultra-precise, micrometer-level moving mirror requirement of an interferometer.

- Performance: Grating spectrometers offer excellent spectral resolution and throughput, making them the default choice.

Our journey continues as we search for that elusive "easy" way to achieve IR ZPD! Stay tuned for more updates.

Tony Francis

Tony Francis

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.