The Inspiration: Duga and the mysterious K340A

I recently stumbled upon some urban exploration photos from the Duga radar site near Chernobyl and an excellent documentary video : (www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHiCHRB-RlA&t=605s).

This gigantic over-the-horizon radar, made of hundreds of antennas, is famous for its distinctive shortwave noise — the “Russian Woodpecker” — that annoyed ham radio operators in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Among the pictures, one can still spot a massive computer left inside the abandoned building: the K340A.

Not your average 1970s computer.

Back then, the USSR was lagging behind in microelectronics. To process the data streams from such a large radar, engineers had to invent clever architectures. The K340A used a very peculiar number system: the Residue Number System (RNS).

A Brief Mathematical Detour: What is RNS?

The idea is surprisingly old (Chinese Remainder Theorem, ~3rd century):

-

Instead of representing numbers in binary, you use their remainders modulo several pairwise coprime bases.

-

For example, using moduli (3, 5, 7), the number 23 becomes (2, 3, 2).

-

You can add or multiply component-wise, independently — no carry, no dependencies.

It’s parallel by design. That’s what made it such a good fit for hardware with limited logic.

At the time, this offered a massive gain in logic simplicity and parallelism. Very clever engineering…

To convert back to a standard value, you apply the Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT):

N = ∑ rᵢ ⋅ Mᵢ ⋅ yᵢ mod M

Where M is the product of all moduli, Mᵢ = M / mᵢ, and yᵢ is the modular inverse of Mᵢ.

In practice, this back-conversion is costly — that’s why systems like the K340A only used CRT when strictly necessary, e.g., to display human-readable output.

All radar processing (correlation, FIR, FFT) stayed entirely in RNS.

Why is RNS interesting today?

In the Cold War era, RNS offered a way to perform fast and parallel calculations with minimal hardware.

Nowadays, we live in a very different context. FPGA chips are binary-optimized, with built-in DSP slices and accumulators. So… why go back to RNS?

Well, first of all — because it’s cool. There’s something fascinating about rediscovering the strange and beautiful architectures of the Cold War. But there’s more to it than that.

RNS fits surprisingly well with the constraints of modern embedded systems: low-power, compact, robust, and predictable architectures.

Let’s take a closer look.

With RNS:

-

There’s no carry chain — additions don’t ripple. Logic is simpler, timing is tighter, and power usage is lower.

-

It scales naturally — instead of increasing bus width, you just add another modulo.

-

It can be fault-tolerant — a failing modulo can often be detected (or even corrected) thanks to redundancy.

-

It saves energy — instead of deep binary adders, you can build flat parallel modulo lanes that burn fewer LUTs. The architecture is (maybe) more efficient.

-

It’s a fresh perspective — in a binary-dominated world, revisiting RNS is like exploring a parallel timeline in computing.

Could we actually see energy savings in a small demonstrator? That’s one of the questions I want to explore here.

This also resonates with modern applications like:

-

frugal DSP (e.g., filters, radar processing),

-

lightweight cryptography (modular arithmetic, side-channel resistance),

-

embedded AI (where matrix (addition and multiplication) operations dominate and average precision is often enough).

The Project: A Modern RNS DSP Filter

I want to reimplement a basic signal processing chain using RNS, on accessible, modern hardware.

Here’s the plan:

-

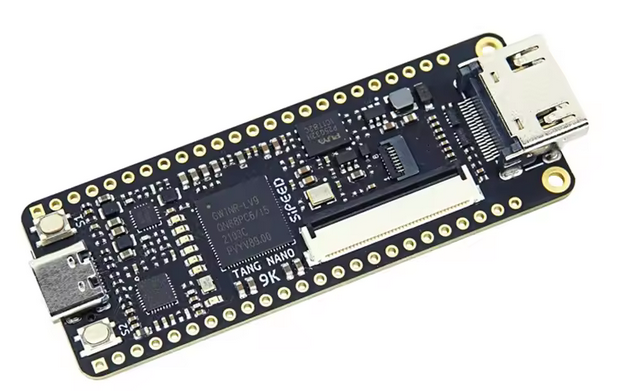

I’ll use a Tang Nano 9K (GW1N-9) FPGA to wire up the RNS logic.

-

It will work alongside an ESP32-S3 that handles I/O and orchestration.

Why this setup? Because it's cheap, well-documented, and popular in the maker community. And because I know almost nothing about FPGA for now, so I’m learning as I go. The goal is to implement an RNS-based FIR filter on this combo.

Expected pipeline

- The ESP32 receives an input sample (e.g., audio or radar echo).

- It converts it into RNS (simple folding using bit masks and moduli).

- The FPGA processes it: each RNS lane does its multiply-accumulate in parallel.

- The result is sent back in RNS, and the ESP32 can optionally apply CRT to decode it.

Comparison with a binary FIR filter

Naturally, implementing a binary FIR filter on a modern FPGA would be easier. The toolchains are optimized for it, the blocks are in place, and everything runs as expected.

But the RNS version has its own value.

It comes from a different time and mindset — when engineers had to find clever solutions with limited resources.

Beyond the historical curiosity, it offers real benefits: no carry propagation, parallel operations (kind of pre-GPU), and a modular structure that can be scaled easily. These features can be useful today, especially in low-power or fault-tolerant systems.

So in some embedded scenarios, it might actually make sense today.

What’s next?

I’ve ordered a Tang Nano 9K to get started. Once it arrives, I’ll begin with the usual “Hello World” — yes, blinking a LED — to validate the toolchain and board setup. From there, I’ll build up the pipeline piece by piece: first a classic binary FIR filter as a reference, then its RNS counterpart.

Along the way, I’ll document how both versions compare in terms of performance, logic resources, and energy usage. The goal isn’t just to recreate an old concept, but to see if — under the right constraints — RNS can actually outperform the binary standard.

Logs will follow as the work progresses.

Bertrand Selva

Bertrand Selva