I continued exploring FIR filtering in RNS on the Cyclone IV, in line with what was presented in the previous log. This log introduces an RNS-based FIR filter that does not rely on the FPGA’s DSP blocks, uses no conventional multipliers, and is implemented entirely with combinational logic and LUTs.

Sizing and Initial Limits

I started with a 128-tap FIR, as defined in the previous log.

In that form, it did not fit in the Cyclone IV E22.

Compilation reported around 30,000 logic elements when not exploiting coefficient symmetry for a 128-tap FIR. By taking advantage of symmetry (which is generally required for linear-phase FIR filters and is a common configuration), the logic usage drops to around 15,000 logic elements for the same filter length. Even if this does not completely saturate the device, this kind of “full logic” architecture quickly eats into the available budget, especially on a family like Cyclone IV.

With a symmetric implementation, it should be possible to push a 128-tap FIR with 16-bit input data and an effective dynamic range of about 2³⁷. That would be very close to the practical upper bound on this FPGA.

Minimal FIR: Validating the Pipeline

Since I had to abandon the initially targeted filter, and in order to simplify debugging and verification, I implemented a symmetric 4-tap FIR with coefficients (1, 3, 3, 1), without exploiting symmetry internally. The goal was to preserve a general architecture that can be reused for non-symmetric filters if needed.

In this configuration:

-

Around 2,800 logic elements are used

-

No embedded RAM, no DSP blocks, no conventional multipliers

Simulation becomes manageable again: each pipeline stage is easier to track, and debugging is more straightforward. This makes it a useful intermediate step before moving back to longer filters. The code is provided in a ZIP file attached to the project files.

The design works. The maximum achievable frequency is about 100 MHz.

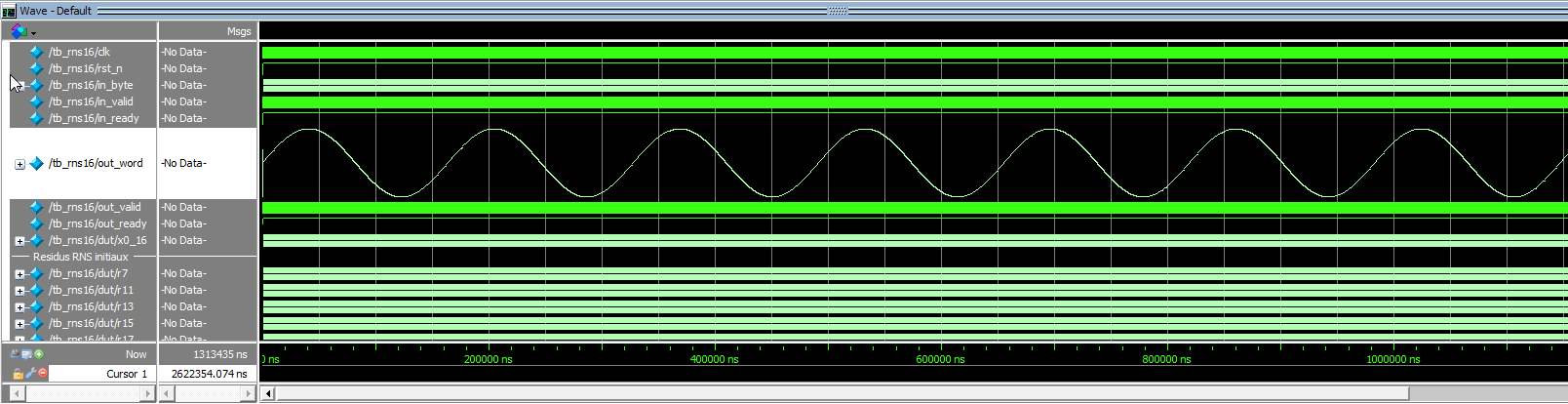

To validate the behavior, I injected a harmonic input over 8,192 samples, covering the full dynamic range.

The filter output matches the expected response, confirming that the FIR operates correctly in RNS, using only pure logic (including the full pipeline: the FIR itself plus the two correction stages).

Scaling Law

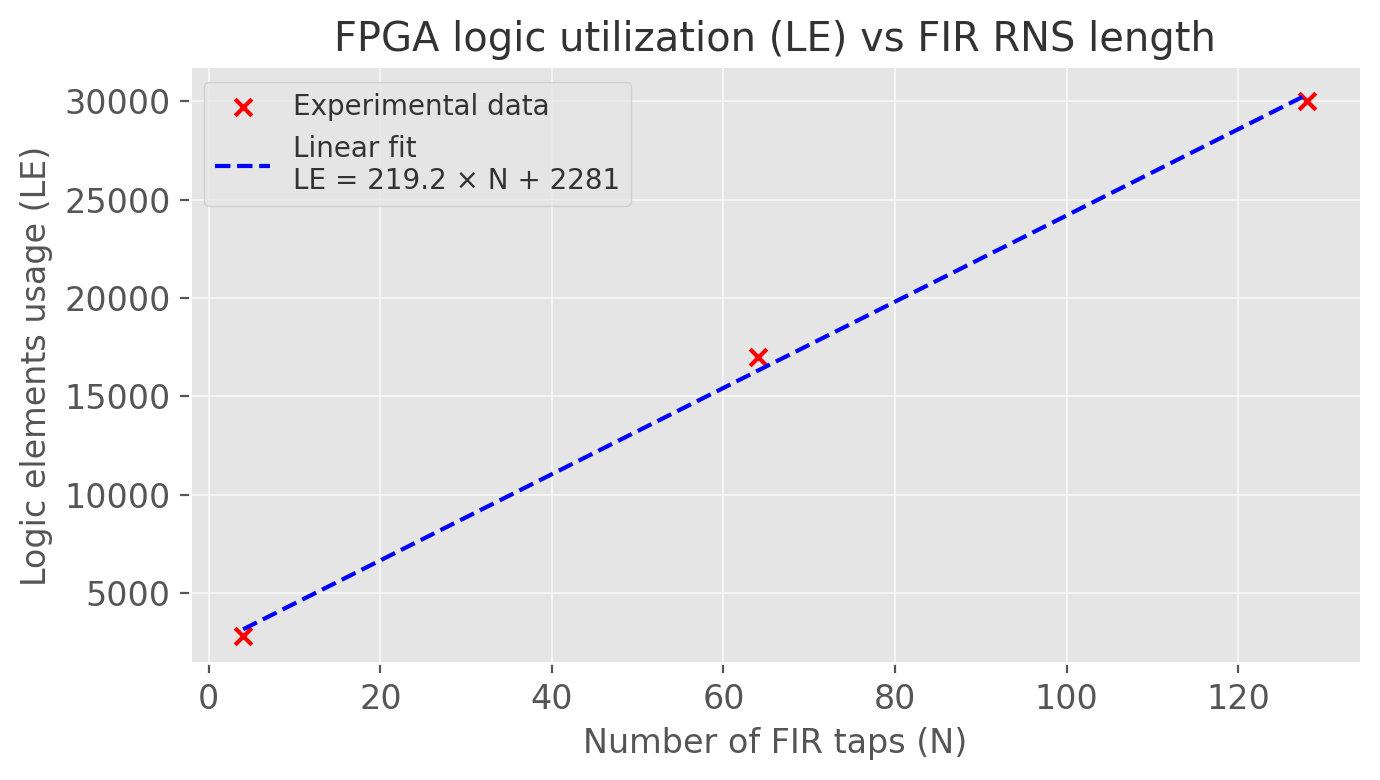

These results show that it is possible to implement an RNS FIR on a standard FPGA with 0 RAM and 0 DSP usage. The following figure shows the (approximately linear) relationship between FIR length and logic element usage.

From the measured points, the logic usage scales approximately as:

LE≈220×N+2200

(there is likely room for improvement with a more optimized implementation, but this gives the correct order of magnitude).

For a symmetric FIR, a reasonable target is about:

LE≈110×N

What RNS Really Enables on FPGA

These results help reassess where RNS is relevant in this kind of architecture. RNS is not meant to replace binary arithmetic, but it is a useful tool in the FPGA designer’s toolbox, with clear advantages in specific contexts.

On an FPGA like the Cyclone IV E22

Even with hardware multipliers available, a fully parallel FIR quickly runs into constraints related to accumulation, routing, pipelining, and overall logic usage. The limitation does not come only from the number of multipliers, but also from all the surrounding logic: adders, registers, fan-out, and dataflow control.

For example, the EP4CE22 provides 66 DSP blocks with 18×18 multipliers (suitable for 16-bit inputs). This is enough to parallelize a binary FIR up to about 64 taps; that is roughly the practical upper bound for a fully parallel implementation. Even in that configuration, the logic elements are still used: they are required to build the adder tree that sums all multiplier outputs.

It is noteworthy that, on the EP4CE22, both approaches, binary with DSPs and RNS with pure logic, end up constrained to FIR filters of about 64 taps, even though the resource distribution is very different:

RNS uses LUTs and logic elements exclusively (and heavily);

binary relies on DSP blocks as the primary limiting factor, while still consuming a non-negligible amount of logic elements for accumulation and control.

With RNS

In the RNS approach, multiplications are replaced by lookup tables implementing products modulo small integers, and additions are local, without carry propagation across wide words. The pipeline is regular and stable, and it relies only on combinational logic instead of dedicated DSP resources.

In practical terms, this mainly allows:

-

Freeing DSP blocks for other tasks (mixing, demodulation, numerically controlled oscillators, etc.) on devices that have them.

-

Enabling filter architectures on smaller or lower-cost FPGAs that have few or no DSP blocks. In these conditions, RNS becomes a practical way to implement digital filtering where a fully parallel binary approach would be too expensive or simply impossible. This is particularly relevant for instrumentation, or control applications, where combinational logic is available but DSP blocks are scarce or absent.

Fault Tolerance and Redundancy: Native Robustness

RNS also offers an advantage in contexts where reliability is critical (space, avionics, safety-critical embedded systems). It is possible to add redundant moduli at very low cost, without changing the global structure of the design or the main processing pipeline.

The idea is to add one or two extra moduli to the RNS base, independently of the main set used for reconstruction via the Chinese Remainder Theorem. These redundant moduli are not used in the final binary reconstruction; instead, they serve as arithmetic signatures to check the consistency of the residues throughout the dataflow.

This mechanism allows low-cost detection of computation errors and transient corruptions, simply by checking that all residues remain mutually consistent. In practice, it introduces a native verification layer directly embedded in the architecture, strengthening robustness without complicating the existing pipeline or degrading performance. In this specific area, RNS provides a genuine advantage over a purely binary implementation.

Summary and Outlook

This first RNS FIR implementation shows that, on the chosen FPGA, both binary+DSP and RNS full-logic approaches hit similar limits in terms of achievable FIR length, but for different reasons. RNS shifts the constraints toward a compact, regular, pipeline-friendly logic structure instead of relying solely on dedicated DSP blocks.

On FPGAs without DSPs, or with very limited DSP resources, RNS offers a viable way to implement parallel digital filtering that would otherwise be out of reach with a conventional binary architecture. It also opens the door to naturally redundant, fault-tolerant designs at relatively low cost.

Next Logs

The next steps will be:

-

Extending the structure presented here to 64 taps, building directly on this validated base.

-

Integrating proper dataflow management (backpressure). For now, the pipeline accepts one input sample per clock cycle at the FPGA clock rate, which is fine for simulation but not sufficient for integration in a more complex system.

-

Validating the behavior in real conditions on FPGA, coupled with an ESP32.

This log is an engineering feedback report, not an optimized endpoint, and the numbers given here are order-of-magnitude indicators. In their current state, they are already sufficient to support a preliminary conclusion: RNS is worth considering in several real-world scenarios, whether to introduce low-cost arithmetic redundancy, to shift the computational load from DSP blocks to general-purpose logic, or to enable meaningful signal processing on very resource-constrained FPGAs.

Bertrand Selva

Bertrand Selva

Discussions

Become a Hackaday.io Member

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.