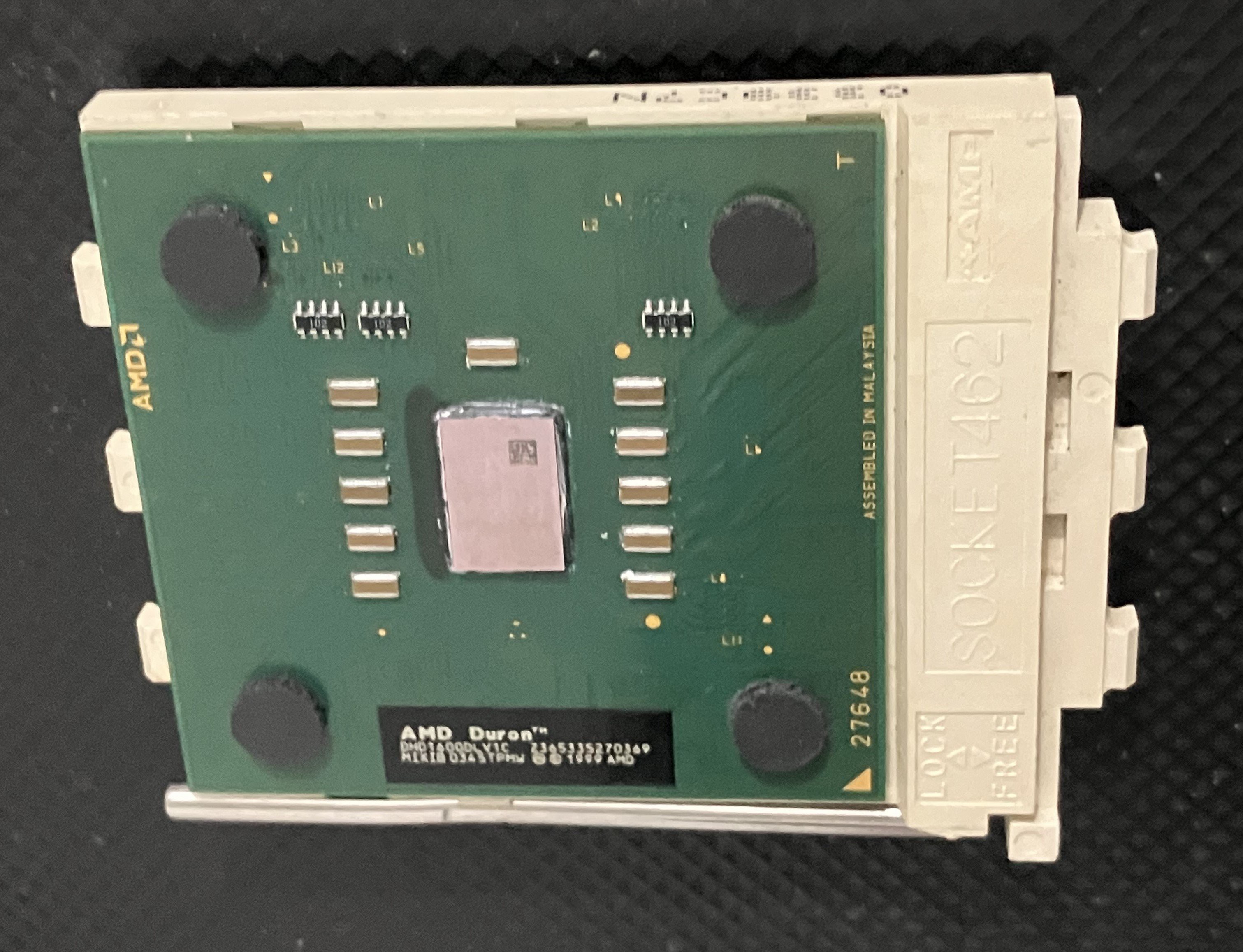

If you haven't noticed by now, at some point in time, I managed to successfully remove an AMD Duron chip that is, I think, at least 25 years old, if not older, from whatever long since dead PC that it was associated with. Not only that, I successfully managed to unsolder the original ZIF socket from the now completely bricked motherboard, by a time-honored method that I will not otherwise describe in too much detail in these parts. Yet, having come to the realization that turning a possibly still functional legacy CPU into an interesting paperweight is a perfectly valid form of abuse, I therefore decided to start this project. Which, for now, does absolutely nothing, except sit there and look nice.

Then again, even if it doesn't quite play doom, so what? The PC that it came from was clearly doomed for other reasons, so why not have some fun? Obviously, there is something weird and wonderful about this particular vintage of CPU, so who knows, maybe someday, a new hardware project might actually get built based on the design principles that otherwise should seem so evident, even if they are not. Like, what if we could somehow build a Parallax Propeller P2-based PC, or maybe create something ESP32-based, or "whatever", and just somehow put it on a circuit board that might not cost all that much to have made, in this day and age, so that it can, in turn, be plugged into an existing legacy PC.

Just because. For the same reason that some people climb Everest, or any other mountain, for that matter. Because it is there. And because it might actually be possible to do.

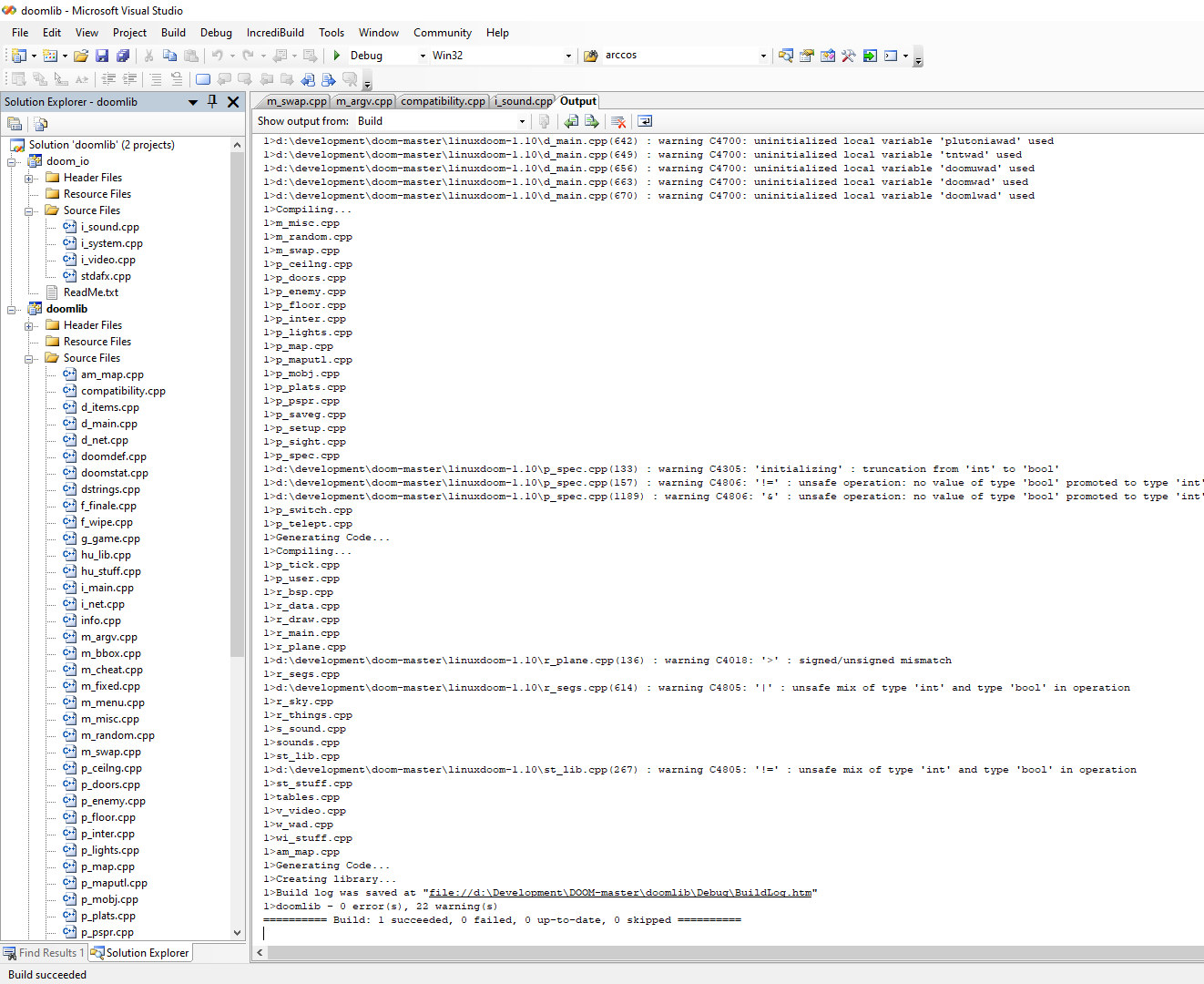

Yet, as far as finding other ways to run DOOM on alternative hardware is concerned, all hope is not lost. At some point, once upon a long time ago, I took a DOOM distribution, I think of the original DOOM, and went to work at trying to see how hard it would be to get DOOM running as a Microsoft Foundation Class library C++ application, i.e., in Visual Studio 2005, no less. And even if I never quite got that to work, I did make considerable progress, wherever that was, in some other timeline.

I mean, at least I got most of the DOOM codebase to compile, not as an application, but as a library, which I suppose, could also possibly be compiled as a DLL, or maybe as an Active-X control. Or maybe I should try using some modern AI-based tools to rewrite all of this in TypeScript. I did have some issues with some of the files that were giving me some trouble, of course, so I put those into a separate project, at least for the time being. Thus, i_sound, I_system and I_video remain non-functional in this build.

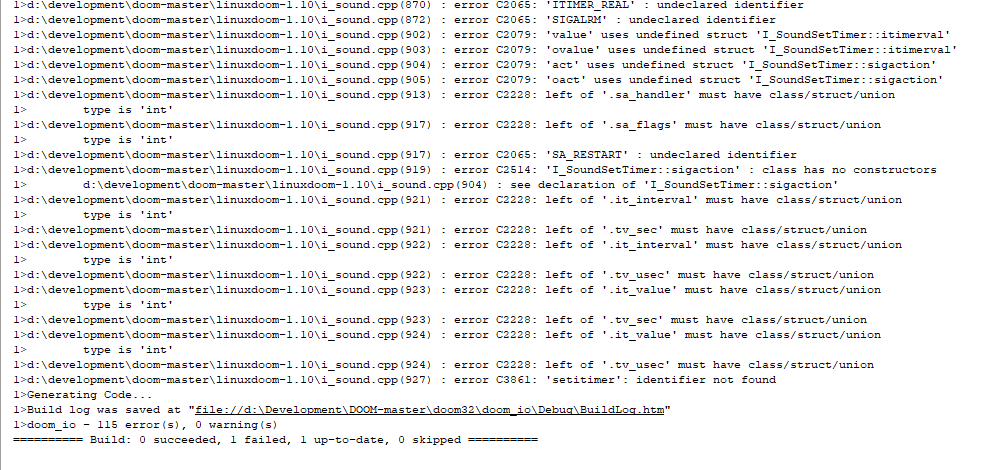

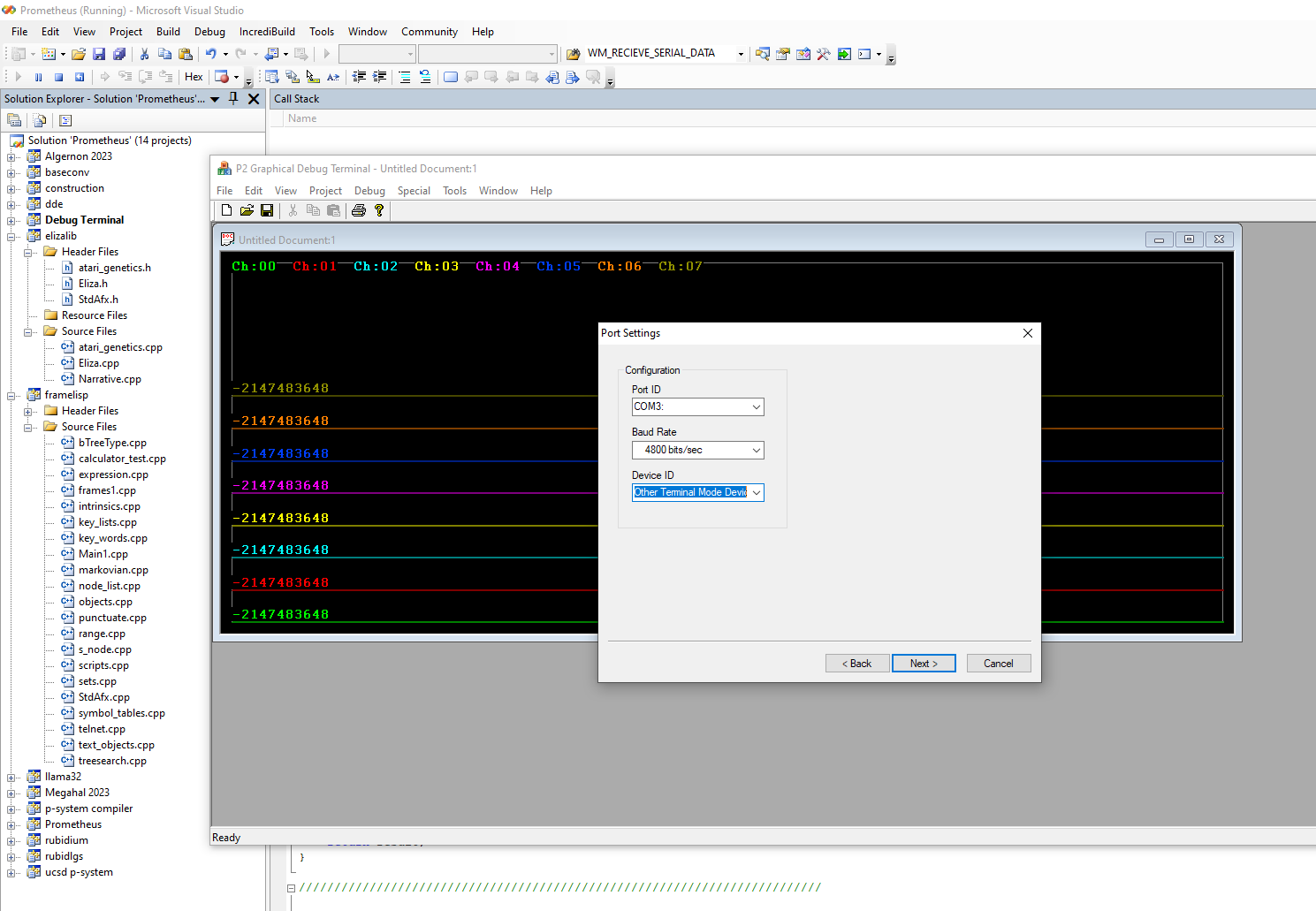

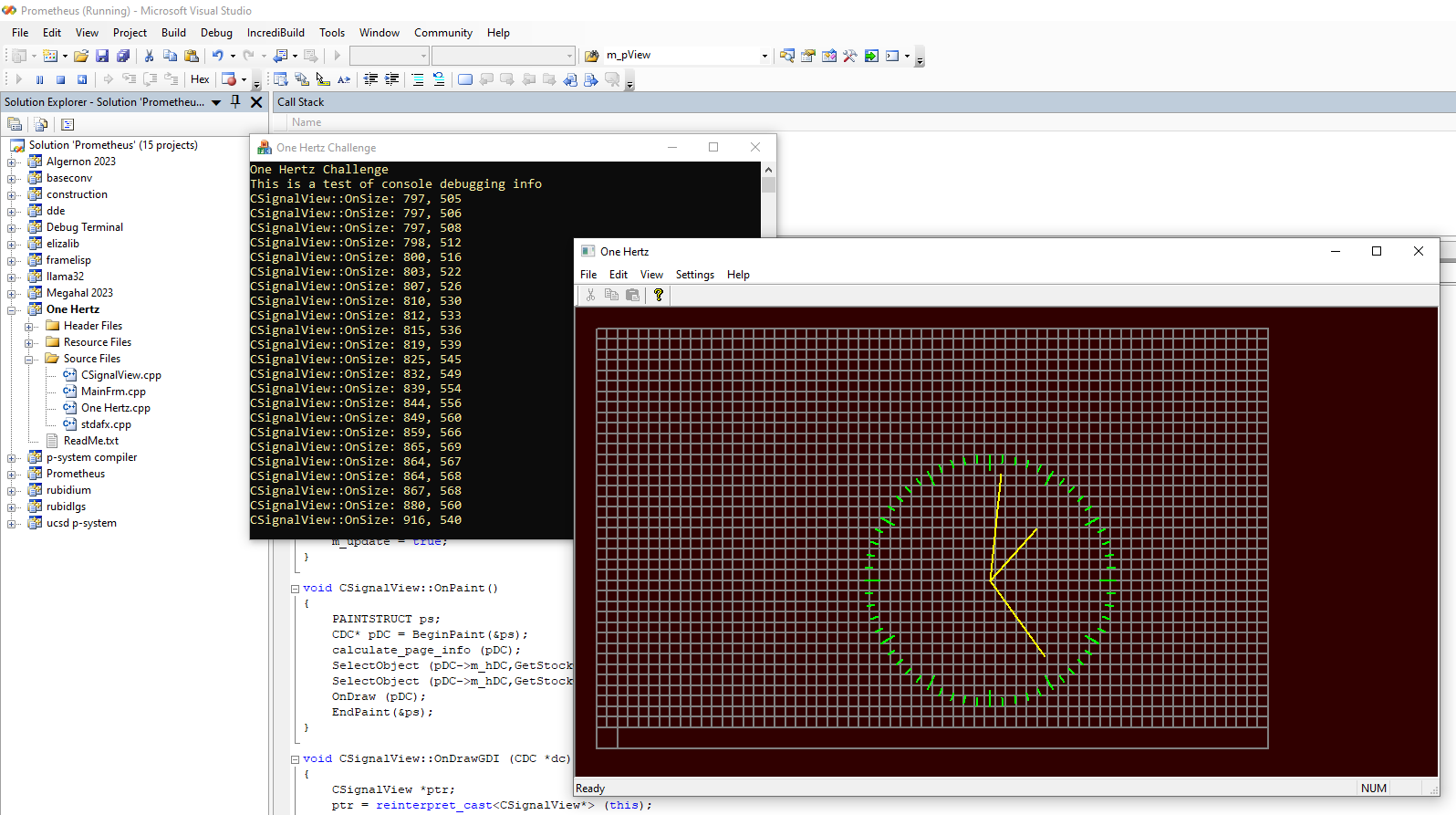

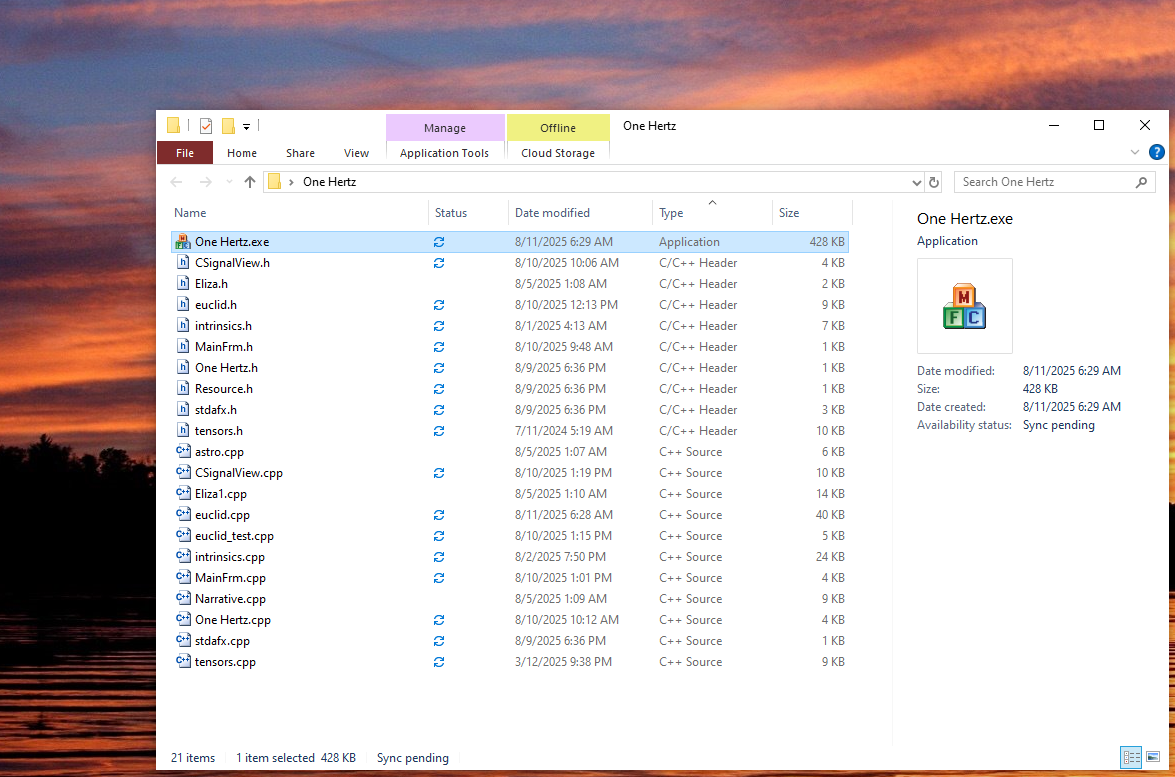

Yet, really, the 115 or so errors that are preventing this project from compiling doesn't really seem like that big of a deal. I just need some compatibility code that deals with the requirements for some non-Windows API's like just why it is that I am getting errors like "XPending : cannot convert parameter 1 from XWIN::Display to 'Display" and so on. So let's take a closer look at the real world of application building, and what I had to work with while trying to build my entry for a previous contest, i.e. the One Hertz challenge. Thus staring from a workspace that actually included something like 14 separate projects, I was able to jump right in, locked and loaded with the ability to interact with a COM port that was in turn connected via USB to a GPS module, right from the get go.

And that meant, of course, that creating a working One Hertz application was almost already in the bag, allowing me to focus on the intricacies of the methods of Euclid, and Ptolemy, for that matter.

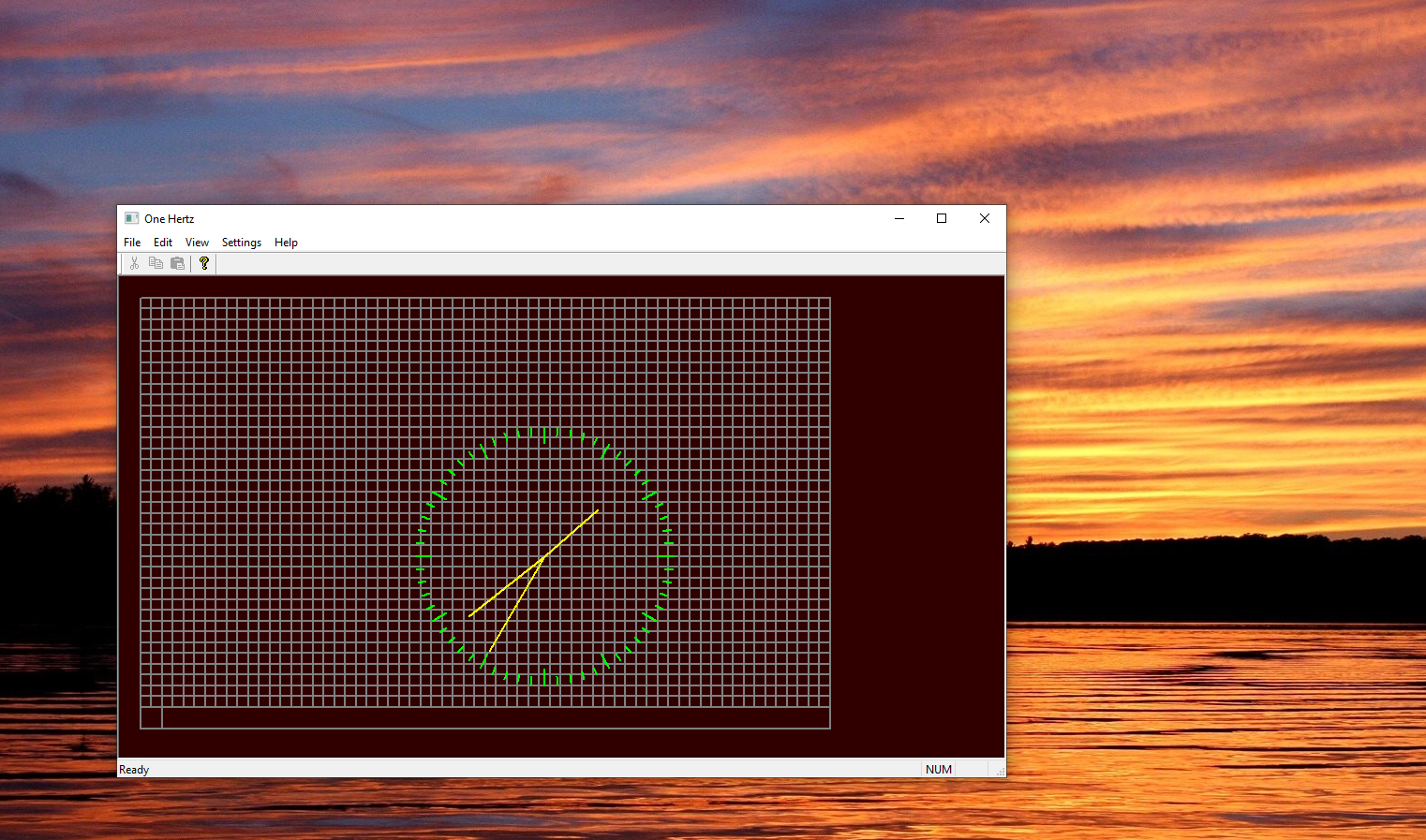

And that is because, as some people might say, a design isn't perfect when this is nothing left that needs to be added, rather a design is perfect when there is nothing left that can't be removed. That is to say, as we go from this:

To this:

Or else something similar. Taking a closer look at the properties of doomlib.lib, we can see that it takes up just over two megabytes, in an otherwise unoptimized build as a statically linkable library no less!

This is, of course, going to have some important implications as to what sort of constraints, or requirements, or whatever we want to call things. Like I have no idea what the final size would be, if we were to try to compile just this part of the code, what we might therefore refer to as "DOOM essentials", for all intents and purposes, let's say, if we had a really fast 6502, or "whatever".

Obviously, we still need to have some support for whatever is in "i_video", "I_system", and "i_audio", but that can wait for now. Maybe one way to get DOOM working in this environment therefore, might be to take some of the code that I wrote for the One Hertz challenge, and add an interface class that exposes some of the missing functionality that original DOOM expected to find in the "i_video.cpp" file, as well as the other non-working files, i.e. add some stuff that addresses the aforementioned "XPending : cannot convert parameter 1 from XWIN::Display to 'Display error, as well as a bunch of other errors, like some simple stuff that involves some missing struct definitions.

Obviously, if blitting and double buffering, and a bunch of timer-related and system-related stuff are already being handled in files like "CSignalView.cpp", then we are that much closer to having just what the world really needs right now: yet another DOOM implementation.

But wait! There's more. Remember how I already started on converting "CSignalView.cpp" to TypeScript? Well, here is a code snippet from wherever that was, whenever I was last working on that.

O.K., so that is what it was starting to look like in TypeScript, as far as wanting to be able to have WebGL support, for example. Now obviously, I am trying to do far too many things all at the same time, or maybe that is how it is supposed to be. Remember when I mentioned x86 emulation or even FPGA, or wanting to have some kind of NOR computer? Well, that's where it becomes yet another fun form of abuse, to try to not only get DOOM working on such a platform, but to also go ahead and try to write some things like floating point routines as C++ classes, just in case the target platform doesn't support floating point. So let's take a quick look at addition, without an FPU.

real real::add (real arg1, real arg2)

{

real v1, v2, result;

int frac1, frac2, frac3, expr;

int d1 = arg1.e-arg2.e;

if (d1<0) {

v1 = arg2;

v2 = arg1;

}

else {

v1 = arg1;

v2 = arg2;

}

frac1 = v1.f;

frac2 = ((1<<23)+v2.f)>>abs(d1);

frac3 = frac1+frac2;

expr = v1.e;

if (frac3>0x007FFFFF)

{

frac3 = ((frac3+(1<<23))>>1);

expr++;

}

result.dw = (frac3&0x007FFFFF)|(expr<<23)|(arg1.s<<31);

return result;

}

Remember when I wondered out loud just what the performance might be like on a 6502-based system, such as a Commander X16, which is available, if you can find one with something like 4 or maybe even 8MB of RAM, and perhaps more importantly, it has a FPGA-based video controller. So, who knows? This really doesn't look too menacing. But what about subtraction?

real real::sub (real arg1, real arg2)

{

real result;

DWORD abs1, abs2, max, min;

unsigned short exp1, exp2, adjust, expr;

unsigned int frac1, frac2, frac3;

bool sign1, sign2, sr, sflip;

// break off the sign bit into two bools

sign1 = ((*((DWORD*)(&arg1)))&(0x1<<31)?true:false);

sign2 = ((*((DWORD*)(&arg2)))&(0x1<<31)?true:false);

// strip off the sign bit of both numbers

abs1 = (*((DWORD*)(&arg1)))&0x7fffffff;

abs2 = (*((DWORD*)(&arg2)))&0x7fffffff;

if (abs1>abs2)

{

max = abs1;

min = abs2;

sflip = false;

}

else

{

max = abs2;

min = abs1;

sflip = true;

}

sr = arg1.s^sflip;

// now extract the respective exponents

exp1 = (unsigned short)((max&0x7f800000)>>23);

exp2 = (unsigned short)((min&0x7f800000)>>23);

// finally get the fractional parts

frac1 = (1<<23)|(max&0x7fffff);

frac2 = (1<<23)|(min&0x7fffff);

adjust = exp1-exp2;

expr = exp1;

frac2>>=adjust;

frac3 = frac1-frac2;

if (frac3==0)

{

return 0;

}

while (frac3<1<<23)

{

frac3<<=1;

expr--;

}

result.dw = (frac3&0x007FFFFF)|(expr<<23)|(sr<<31);

return result;

}

VERY PAINFUL. Multiplication is discussed elsewhere in another one of my projects. Really, I need to try running this again on a Propeller or an Arduino, just to see how messy it gets, especially when I modify the file "tensors.cpp" to use the "real" data type instead of the usual float32 or double precision types. Maybe even try to get DOOM running on a 6502 emulator, running on a Pentium system, of course. Just because it would be interesting to try to figure out how much of the game actually depends on the geometry part, vs. how much is just game logic, handling maps, and so on. Something a 6502 should handle well, let's say, if there was enough bank-selectable RAM, on the one hand, and a way of offloading the actual geometry to "something" that can provide GPU-like services, in the places where most of the heavy lifting is required.

Yet there is something else, worth pointing out, in emulation land, that has almost no chance of being accomplished in the time available for this project. Yet there it is, the simple fact that "doomlib.lib" only needs about 2MB of code, in 32 land, that is, when compiled as a library. Which seems to suggest something, like maybe hidden in the dark dread of the COFF file format that most static libraries and OBJ files make use of, might be the key to figuring out how to handle the otherwise very painful prospect of figuring out how to dynamically load and link individual functions at run time, let's say, on a Propeller P2 with just 512 K of Hub RAM. Obviously, the size of the library file looks promising, insofar as coming up with some kind of large memory model, or extended memory model, which I know exists on the P1 chip, but I don't know just how much of that ever got done on the P2.

That would mean, of course, that an x86 emulator would need to emulate L1 and L2 cache, pre-fetching, and/or other things in lieu thereof, perhaps allowing for a new way of running code right out of library files, loading and flushing functions as needed. Right now, I know of no tool chain that does this. Or else, native code will place additional burdens directly on the codebase in order to manage the swap system.

There is, of course, yet another approach to this mess, and that is to implement the graphics subsystem as a proper X-server, which ideally would support WebGL, Android, iOS, and other platforms, for other purposes, just because it should be possible to run DOOM as a proper X-WIN "Client", which might yield not only a well-defined way of separating the heavy math from the game logic, on the one hand, but which might so also point to a method for handling the code segmentation model as a third "component" which would become a part of the "system", as has just been discussed.

glgorman

glgorman