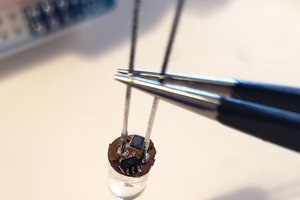

We glue a retroreflector to a bee (or a hornet). We illuminate it with an infrared LED projector. The reflector is then seen by a camera as a bright dot, which is detected by software and is used to track the bee.

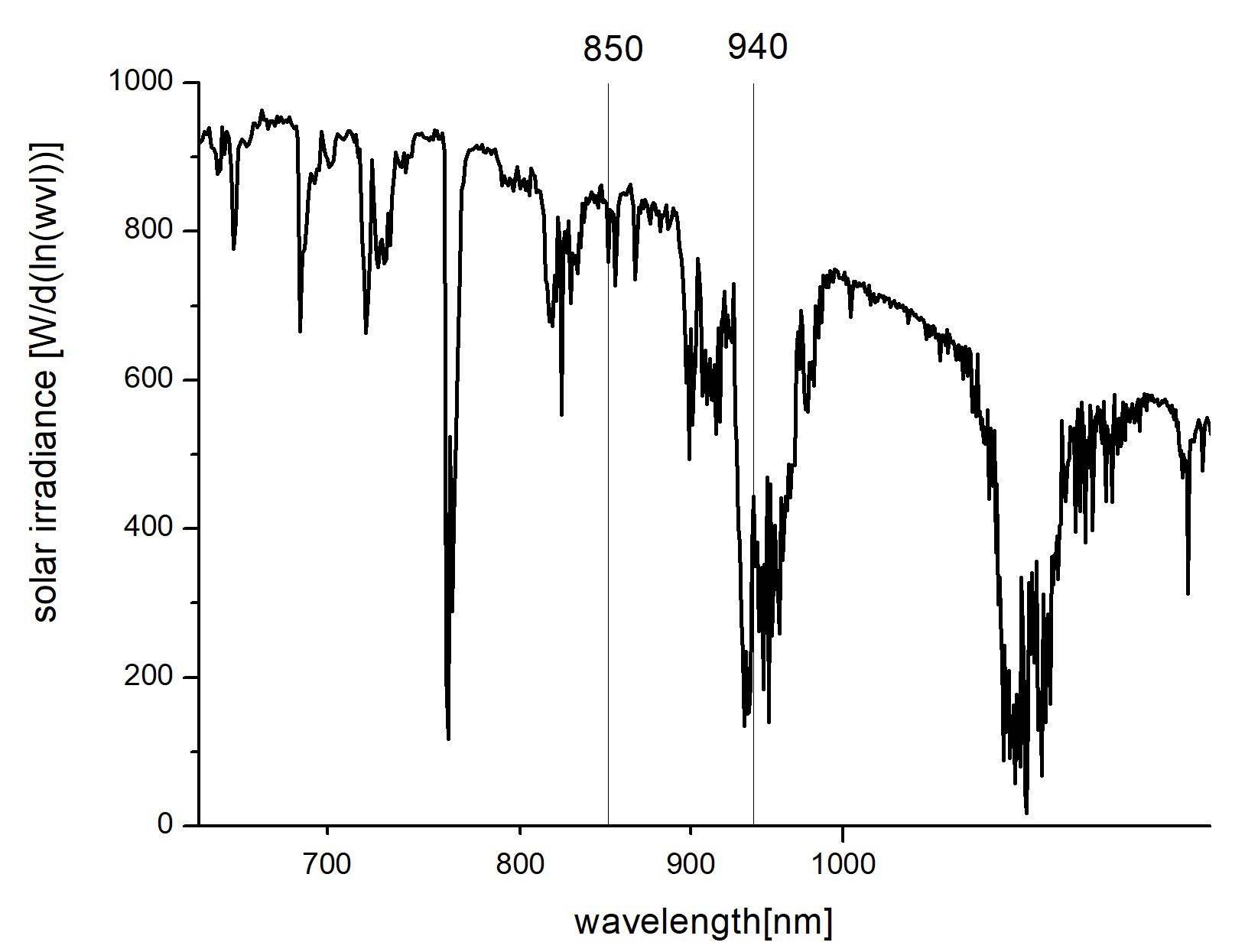

Because this is happening in bright daylight, we need a lot of light output to make the dot brighter than the environment. And because retroreflection is rather accurate (and also because it has to be carried by a drone), we are constrained in how many leds we can put on the projectors. So we really want to max out the LEDs.

For more details on our bee tracking efforts, see strawlab.org

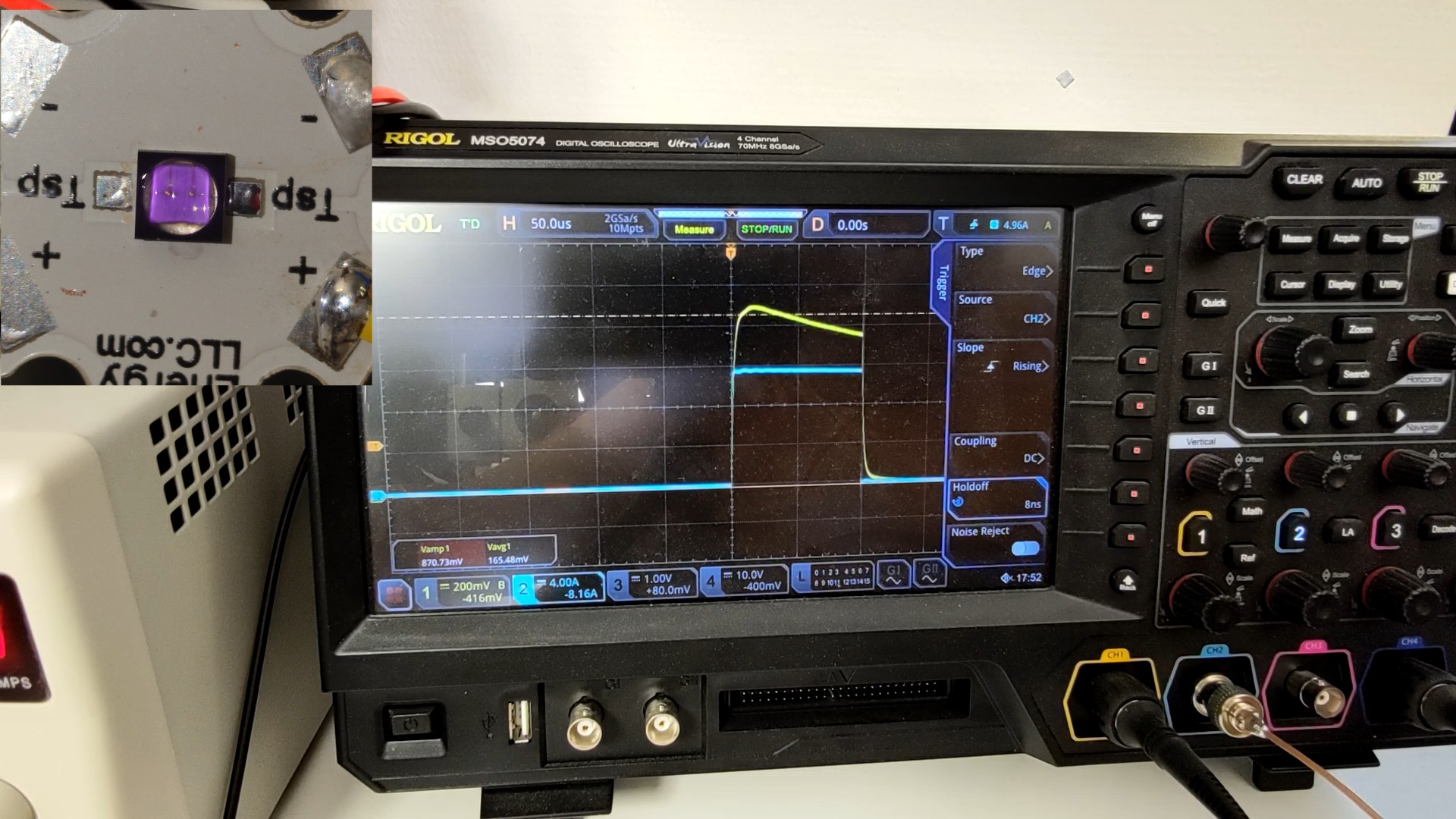

The led projectors are synchronized to camera exposure. The exposure time is 50 us at a framerate of 100 fps, so it's only 0.5% duty cycle. Because it's so low, cooling isn't really a problem.

This project is part of my job at Straw Lab, in University of Freiburg. It is funded by the VolkswagenFoundation Momentum Program (grant 98 692 to Andrew D. Straw), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant 543356743 to Andrew D. Straw), and the University of Freiburg.

Some aspects of this drone are open-source. https://github.com/strawlab/flo

see also our science paper on the tracking technology: Vo-Doan TT, Titov VV, Harrap MJM, Lochner S, Straw AD. High Resolution Outdoor Videography of Insects Using Fast Lock-On Tracking. Science Robotics 9(95), eadm7689 (2024) doi:10.1126/scirobotics.adm7689

DeepSOIC

DeepSOIC

Christoph Tack

Christoph Tack

Ted Yapo

Ted Yapo

Timo

Timo

Sam Ettinger

Sam Ettinger