Louia ObScura is not recommended for real-world use, although I did put it into real-world operation on November 18th, 2025 on a Pico 2 WH board that I bought at a local computer store in September 2025 (my first Pico), as that was its intended purpose for me. I later released the source on November 27th, 2025 for perusal and inspiration and published a summary of this project here to specifically draw more attention to 5 obscure and underappreciated technologies and/or concepts that made this possible:

Like the more-popular Raspberry Pi Picos, Lua, of course, is not obscure to many, especially Roblox or NodeMCU programmers or those that use it in gaming or networking contexts, but it never gets near the top of the TIOBE index, which saddens me. But even so, I have yet to see someone else write a program on the Picos in MicroLua (and Lua is currently my favorite general-purpose programming language), which is likely due to the lack of NodeMCU for those RP2350/RP2040 MCUs (unlike the ESP8266/ESP32 series) along with the more popular MicroPython and C, which are officially supported on the Picos.

In order to port my Linux and Pi Zero-based Louia Spartan server that I wrote in early 2025 to run on Lua 5.1/LuaJIT to a smaller MCU, I first identified the Pico 2 W and MicroLua as being well-suited to this task (the header version of the board only cost me $7.99 at a local computer store) and even reminds me of my old Commodore 128 in some ways, a futuristic 8-bit computer that I received for Christmas in 1985, as the Pico 2 series has multiple CPUs of different architectures inside and is faster and has double the RAM of its popular predecessor. However, the Pico 2 W is not officially supported by MicroLua to date, another reason why it likely hasn't gained traction, and the fact that the developer does not accept code contributions directly likely slows its acceptance as well.

But MicroLua is a work of art, in my opinion, and I did manage to get it working on both the Pico 2 W (with some limitations) and the well-supported original Pico W (albeit with half the memory and flash), and I hope the developer stays with it. Python 3's asyncio tasks within built-in event loops is analogous to what I did in Lua (although I have never used them in Python, only its multithreading and multiprocessing). And coroutines are such a simple way to incorporate cooperative multithreading without the overhead, ideal for a small MCU, and yet they still remain fairly obscure, since most of the examples I see online and even the official Lua programming examples, are on the client side, often smartphone clients.

Well web servers, or Spartan servers which are analogous, need such multithreading for concurrent processing of multiple TCP/IP requests. They're often called "threads" for simplicity when what is really meant here is coroutine. If you've never used Lua's coroutines, something it had during its inception before other languages like Python even incorporated them, I highly suggest you take a look at them. Or if your preferred language supports them, try them there just to familiarize yourself with the concept; they're like subroutines that simply allow you to pause them in mid-process and jump out of them and jump back into them later where you left off, even passing variables, solving blocking issues by their very nature. Of course, preemptive operating systems saved us from the fallacy of relying on cooperation with 3rd party or buggy tasks that failed to yield, but if it is for something highly-controlled, small, and non-critical, it can be very efficient.

But once you've got Lua and coroutines understood, getting them working on a Pico under MicroLua has its own technical hurdle, which I had to solve before even getting a full successful compile, and embedded programming in general is very opaque and obscure in its own right in comparison with popular server and desktop OS platforms, with less support and examples. Not only that, when you don't have an OS at your disposal, you have to create the foundation of one to successfully port over the same functionality, a very different type of task compared to porting something embedded over to Linux (which I did years ago on another project). Luckily, I already had the foundation of those coroutines, so the hardest part of an OS layer was done, as many graphical operating systems of the 8-bit era had no multitasking whatsover.

Yet it turned out that MicroLua, which uses an unpatched, unmodified Lua interpreter (version 5.5 in my case) also includes its own useful threading system also using coroutines, a great addition that allows it to efficiently interact with other external libraries like lwIP, the CYW43439 wifi chip driver, and LittleFS by putting any callbacks inside an event-based system. So if you don't use that threading system, you have to make sure its yielding functions do not interfere with your own threading system (which it did in my case). And the hardware library, which included the gpio, rtc, and watchdog modules that I wanted to use on the Pico 2 W and RP2350 was only designed for the original Pico-based RP2040 MCU, so I had to create my own RTC and watchdog externally and also forgo the use of the Pico 2 W GPIO until MicroLua hopefully supports them someday on that MCU. But luckily it still supported everything else I needed to create a Spartan server and OS on the Pico 2 W, and the Pico W thankfully does not have this hardware limitation, yet it comes with another limitation for my use--it's slower than the Pico 2 W and has half the RAM and Flash storage, as mentioned above.

Those are important things for a multitasking Internet server, with RAM being especially important since each task has to save its state in memory, a problem during those early 8-bit days. Even the first 1984 Mac with its Motorola 68000 and 128K could not multitask at release. But Spartan is so spartan and TLS-free, that even the diminutive 133MHz Pico W with only twice that RAM will operate well as a practical server, and these small MCUs are over an order of magnitude faster than those aforementioned computers, although I use the faster 150 MHz Pico 2 W for my live server and don't seem to be able to use those RISC-V cores yet, as again, the original Pico never had them so MicroLua doesn't know about them. And I'm not going to go so far as to delve into the C SDK just to create a workaround (which is probably not that difficult in Lua, being such close friends with C).

And finally, Spartan, the whole point of my server and OS project, is one of the "Smolnet" protocols, part of a neo-Gopher-like Small-Internet movement that roughly started to emerge around the beginning of the 2020s. Spartan also uses gemtext markup instead of HTML, with its namesake Gemini being the most popular. Again, these are (currently) obscure protocols that should not be confused with the more popular technologies of the same name today and are very hard to find in modern search engines (that ironically use tech of the same name), so I'm happy somebody coined them Smolnet to make finding them easier.

I enjoy both protocols but only chose to create a server for Spartan instead of Gemini since Gemini mandated TLS, and I didn't want to use nor create the TLS subsystem in Lua, which made it so much easier to both write and to port to the Picos (and faster).

So that's a basic overview of the underappreciated technologies that work so well together, and they're so fun to work with. It took me about 1 month to create Louia under Linux, and another 2 months to port it to Louia ObScura on the Picos, and my code size ironically got about 3x larger due to the lack of Linux OS that both directly and indirectly provided some of the functions. It was those functions that I had to add to get my OS-like functionality back.

For example, once you port the server to the Pico on the bare metal, so to speak, and finally get wifi and TCP/IP working, how do you now copy your site files to the device? You have no filesystem! And even if you did, you have no cp, scp, sftp, or rync anymore! And even if you had those, you have no ls anymore to list your files! Heck, you don't even have LOAD "$",8 and LIST at your disposal. And if you want to read a log, you have no cat or less or even a shell to use them on, for that matter! So you can't just use top or ps to get the status of running processes... You see where I'm going. So I ended up creating the following:

- Cooperative multitasking via coroutines (this system was derived from Louia)

- Pseudo FastCGI and batch processing capability

- Text mode screen buffer (what I call PID files)

- Lua scripting API (tiny, just 3 functions)

- Task launching, expiration, and killing

- Privilege separation

- Sandbox and error isolation

- IPC message queues and context switching

- OOM killer and auto file deletion

- Task scheduler/prioritization

- Bulk site upload delete/receive function and storage formatter

- Config params that can be changed/saved on each boot via USB TTY menu

- Log viewing and deletion

- Administration console

- Directory and process listing

- Custom RTC/NTP like system

And all of this was created with the intention of running the Louia Spartan server itself, which uses the Spartan protocol to receive and serve TCP/IP requests for a sister site I created at spartan://greatfractal.com which can be accessed with a Spartan-capable browser like Lagrange or Offpunk.

Below is a photo of the unit in operation. It's powered over USB 2.0 from a nearby Raspberry Pi 2 Model B (specifically, the first ARMv7 version with the BCM2836) that uses uhubctl with the command uhubctl -l 1-1 -p 2 -a 2 to power-cycle the USB ports and thus reboot the connected Pico via BASH script in the event that it goes down, although this could also have been achieved by using the Pi 2's GPIO to temporarily ground the RUN pin 30 on the Pico to reset it. It serves as a temporary external watchdog until MicroLua hopefully someday supports the Pico 2 W internal hardware watchdog like it does for the Pico W:

Spartan, again, is quite obscure even in Smolnet space, as most know what Gopher and Gemini are, so it isn't supported in all of the browsers that support Gemini. And Louia contains its own features like a whitelist to prevent unwanted directory traversal, etc, which I just carried on over to Louia ObScura on LittleFS which doesn't quite match the Linux filesystem but has some similarities in the path format.

My RTC system and site uploader are partially-dependent on Linux using BASH scripts and OpenBSD netcat to act as a client to send the date and hour and send the files, respectively, but everything else is self-contained in MicroLua on the Picos.

This is a good time to explain that I had no intention of creating an OS when I set out to port Louia to the Picos, but that was the outcome once I realized that I had already created the foundation of such using coroutines in Lua, plus the fact that I needed to add all of those additional functions to get the same functionality I had under Linux. However, I did take the liberty to expose some novelty, proof-of-concept functions to demonstrate that it really is a multitasking OS by any ordinary definition, just an obscure, hobbyist one that was pretty domain-specific and written in interpreted Lua, not compiled C or C derivative like Linux, macOS, or Windows.

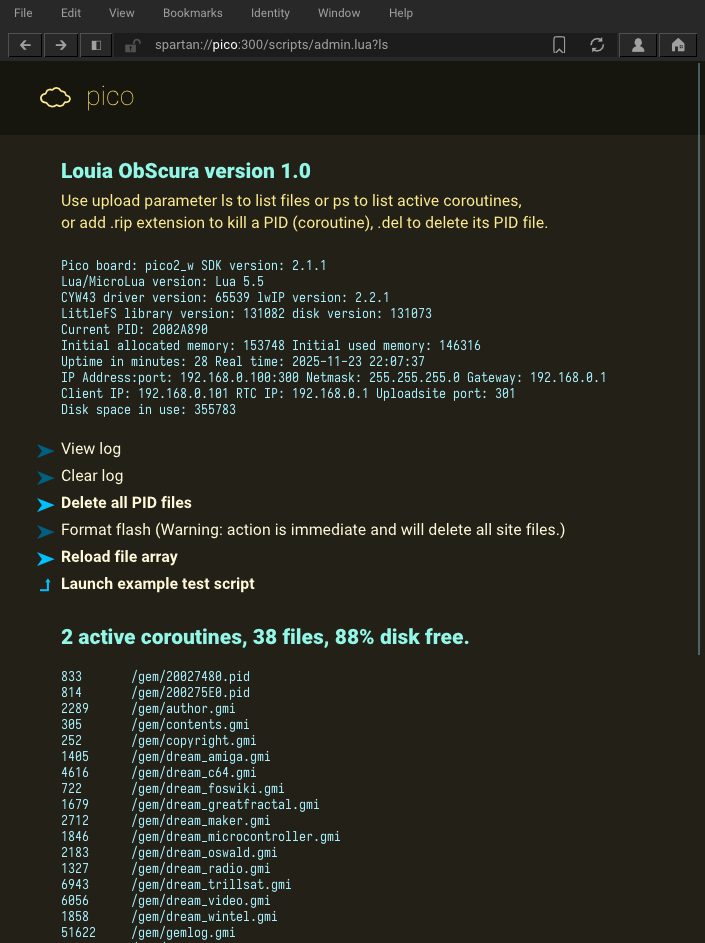

One of those novelty functions, the ability to run .lua scripts in a CGI-like manner, even a FastCGI-like manner, something I did not even attempt in my Linux-based Louia, was put to good use in creating a real-time admin console which made what was going on inside of the tiny server less opaque, such as:

- Software version information

- Pico board type

- PID number of its own process (which ended immediately after serving the page)

- Server uptime and real-time

- Relevant IP addresses and ports

- Total memory use

- Total disk space use, space available, and number of files

- Total coroutines in progress

Then it provides the following custom Spartan hyperlinks:

- View log

- Clear log

- Delete all PID files

- Format flash

- Reload file array

- Launch example test script (obscura.lua) to show off its API and batch capabilities

It also includes two Linux-like commands using the Spartan input prompt by typing them into the Lagrange browser URL field like you would type into a Linux shell:

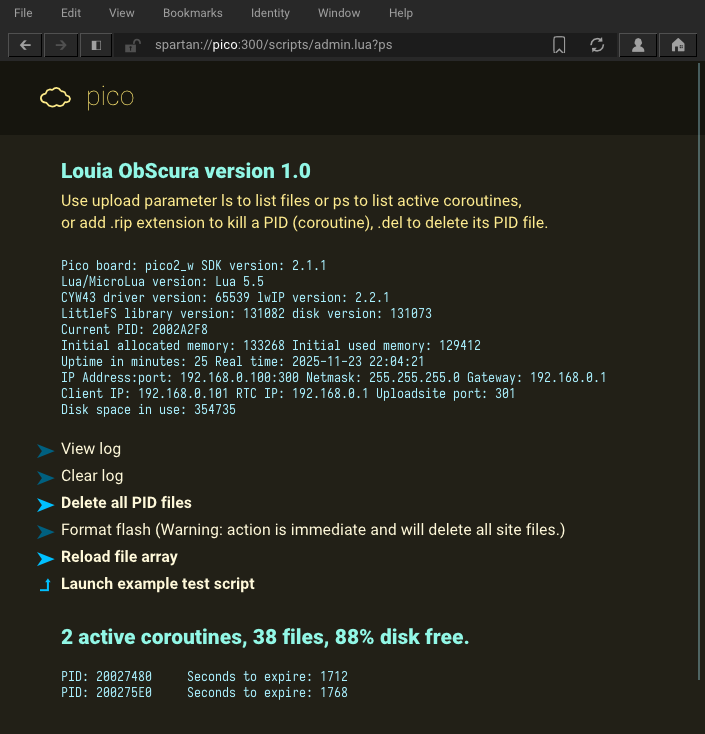

- ps - List all running coroutines

- ls - List all directories and files (including .pid files from coroutines)

Here are examples of it in operation using the Lagrange 1.18.8 browser. Note the ls and ps commands in the URL field:

As shown above, it also responds to various custom paths and extensions, and if an .rip extension is added to a running PID file, it kills that running coroutine. If .del is added, it deletes that .pid file.

Note that this CGI-like process also includes a novelty API of only 3 commands:

- pidprint(text) - This writes output to a unique .pid file on the flash drive, creating the file if it doesn't exist.

- text = pidinput() - This reads uploaded input in real time from other Spartan upload requests to that .pid page.

- text = pidread(pid,startbyte,length) - This reads a length of bytes from an existing .pid page, starting at the start byte.

You see, the CGI-like OS can operate like a CGI script that runs some server-side code on request and returns it back, then ends the coroutine. It can also act as a psuedo FastCGI server itself by simply rerunning the bytecode that was already compiled by the Lua load() command within the same coroutine (kind of what FastCGI does by not spawning a separate process each time), but I left this bytecode tweak out of my final source and only commented it, as it is trivial to add later. Or it can run the script and keep running, continuing to send output to a unique .pid file it creates, like a batch process, even pulling information from another coroutine's output (or live input uploaded to that coroutine) then continues processing in the background while it still receives other Spartan requests concurrently. I've opened numerous PIDs (the term I use for coroutine "threads" in this context), and the incremental memory use is fairly low, and I haven't even optimized it yet. I've even opened up to 40 Lagrange browser instances on the Pico 2 W and tried downloading a 1 MB zero-byte file all at the same time, and they all ran concurrently and completed, while still serving other Spartan requests, pushing the limit of that tiny Pico.

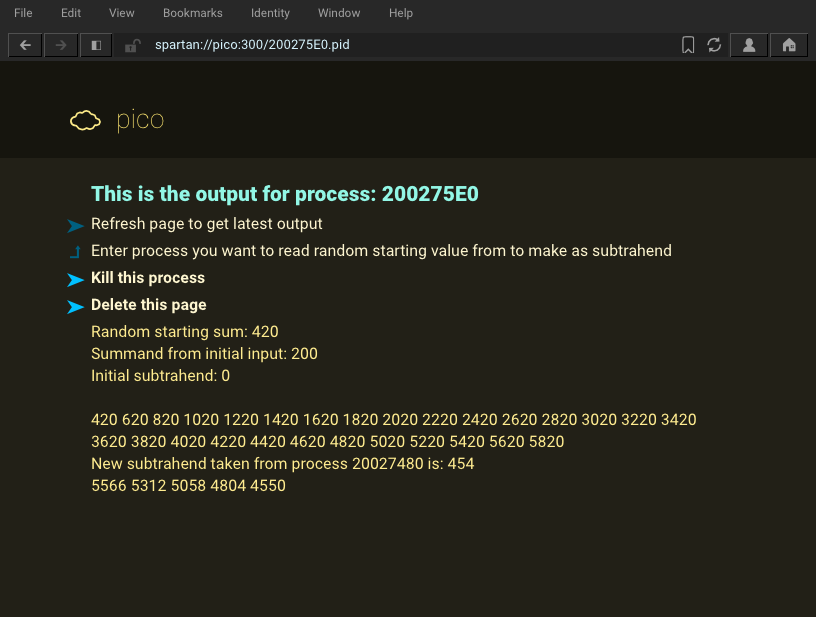

Here is an example of the included example test script, obscura.lua in operation, running two instances of itself. It simply sums a series of integers every 3 seconds, using the initial upload string to the script as the starting summand (if any) and then generates a pseudo-random number between 1 and 1000 that it uses as a starting sum. Then it simply iterates and adds the summand to that sum, growing the sum, then adds again, and repeats. When live input is sent to the .pid page generated by this script that contains the hex value of another running PID (a coroutine thread value) that was also created from this script, it will scan that .pid page for its pseudo-random starting sum and then make this a subtrahend, subtracting from the sum. So if the initial summand chosen is larger than the externally-chosen subtrahend, the sum will grow, but if smaller, the sum will decrease, eventually going into negative integers.

Note the input prompt to enter the PID of another process:

It's a simple example that shows how initial input via the original .lua upload, plus live input via the .pid upload, plus reading from another running .pid file like its own reveals its concurrent-processing potential. It was slowed down to 3 seconds per iteration for demonstration, but this delay, of course, can be removed for high-speed processing.

Ideally, I would have created a nicer example script, say one that progressively rendered the Mandelbrot set, with each coroutine iterating on the result of the previous one, or perhaps a higher-order Fibonacci sequence, or maybe even something like GPGPU vector addition or subtraction (virtual of course, since this is pseudo-parallelism, not really parallel), but I just did a boring sum and difference, as I was already fatigued with creating the entire OS itself.

It's a good time now to explain that exposing those functions to demonstrate that Louia ObScura really is a multitasking OS by accepted definition (but a bad one, do not use it) is not as difficult today as it would have been in the 1980s or early 1990s due to multiple factors:

- It's only for two MCUs that have well-defined hardware and constraints, not an entire PC industry

- The Lua language itself provides features that ease the design (coroutines, lexical scoping, nesting, load() isolation, etc.)

- MicroLua provides its own yielding functions (and threading, of which I forwent in lieu of my own)

- The Pico C SDK and CYW43439 driver provide hardware abstraction

- lwIP provides the difficult TCP/IP stack (although configuration of reliable RAW mode is significant)

- TCP itself performs the error checking and retransmission layer so reinventing XMODEM (or Punter) is not needed

- LittleFS provides a copy-on-write file system with wear-leveling (although it lacks higher functions that access it)

- Spartan-capable browsers provide a nice client-side user-interface, in addition to the USB TTY system

- We, of course, no longer live in the 20th century and have the WWW along with a long history of OS design and administration as our guide

So creating an OS, while daunting for an individual, can be easily done in a piecemeal method like I did in a highly-controlled case. I actually found it more difficult to expose and generalize the novelty functions than actually incorporate the functions into the working server itself. Back in the 8-bit days, you had to essentially build pieces of an OS anytime you wanted to program something, and each piece of software often had its own version of modem or printer drivers incorporated into it. The term "driver" was not used widely with 8-bit home computers in those days and only came into mainstream use later, as I first remember encountering this term with the C64 GEOS, an amazing 8-bit graphical OS that came about near the end of the 8-bit era.

I remember writing a bitmap printer driver for my first computer printer, an IBM PC Jr. "Big Blue" 5181 thermal printer for my Commodore 64 that I bought used from a classmate so that I could print out bitmap graphics and expand them into large posters using limp, thermal paper after I created an RS-232 interface for it to convert the logic levels for the C64's 5-volt TTL user port. I shudder to think of all the BPA that I must have unknowingly handled. Believe it or not, I used this printer to print most of my high-school and collegiate papers using Fleet System 2 to write them (no GEOS for me), but in college, I copied them to regular paper using a coin-based laser photocopier at my dorm so the professors would not complain. It did not technically pass their finer dot-matrix requirements, but they begrudgingly accepted them! Whew.

So once you've built-up enough routines, tying them together and generalizing them for reuse by different programs forms the foundation of an operating system. But if you start with multitasking from the beginning, it's a lot easier and is something very difficult to add after the fact, which is one reason why you didn't see things like GEOS 128 2.0, a very nice OS for that C128, multitask, even when it did have 128K or more memory with its REU. Note that I have not studied OS or kernel design, as it has not been something that has ever interested me, as I tend to engage with the hardware at either the very low level or at the system admin level, not that intermediary level, so this OS is likely a very poor implementation. But it works for me, and I simply want to demonstrate that such things are possible and not that difficult for enthusiasts/hobbyists (it's primarily a structure and organizational task with optimization elements).

Again, Lua and its coroutines, MicroLua on the Picos (with integration of those coroutines if you want), and the Spartan Smolnet TCP/IP based protocol are wonderful and exciting things to work with. It took me 2 months to port Louia to the Picos, and I had fun the entire time and never got bored nor burnt-out during this process (although it did take a toll on my neck and eyes), even being tired working in the early hours of the morning on it. In fact, I'm going to get the Programming in Lua book 3rd or 4th edition as soon as I can to explore Lua in more detail, as I just threw everything together quickly using basic routines and design patterns to work around the problems at hand; it was more organic than engineering. The fact that Lua is so small and so fast, one of the fastest dynamic languages in existence (if not the fastest if you use LuaJIT under 5.1) provides much enthusiasm and a nice buffer as well when working within the constraints of embedded systems (which it was first designed for, unlike other languages). This is not a criticism of other languages; each one has its best uses case, and there is no perfect language, in my opinion.

And Spartan included just the two unique aspects in its simple protocol that I needed to complete the CGI-like function and make it useful, like a rudimentary web app, the input prompt (which technically diverges ever so slightly from the Gemini gemtext format) that allows me to send, or "upload", parameters, along with the redirect response which allows me to bring up the results of a coroutine that I just launched (a PID file) using that uploaded parameter. It's just cool! Of course, no AJAX here, so page refreshes have to be performed manually.

The full project page is at http://greatfractal.com/LouiaObScura.html with examples of bugs and workarounds (and some nice stories included as well). I don't use TLS on my HTTP site, either (in case your bloated browser complains). I learned a lot while porting it, and later released version 1.4 of the Linux-based Louia with the fixes and improvements I made to the underlying Spartan server in this Pico version, as the Pi Zero under Void Linux still runs Louia much faster than the Picos.

I've also added the source code tarball for Louia ObScura to this project under GPLv3 (in the Files section), as well as a link on my main project page, as I don't use Github (if you're wondering). I just throw tarballs over the wall, so to speak. For again, I recommend not to use it and will not incorporate other's code contributions, as this is just for my own experimental use only, but have released it simply so that others can examine the simplicity of creating a concurrent Spartan server and OS on the Pico 2 W and Pico W under Lua and MicroLua. These technologies can also easily be adapted to a Gemini or HTTP server, too, obviously, but creating an HTTP server with all of the bloat of the protocol and modern web browsers was something I've tried to run away from, not promote, as that defeats the entire point of Smolnet protocols like Gemini or Spartan.

Of course, posting it here is a contradiction to what I just said, but I was worried that they were becoming so obscure that people were forgetting they even existed; it's sad to see sites out there only a few years old that are no longer updated or have dead links, although there is an Amiga one still running strong. I don't want something so novel, so inspiring, and so fun and empowering to suddenly die off right when I became engaged with it, like getting my first computer, a TI-99/4A and later Extended BASIC just before the company stopped manufacturing them, or a Commodore 128 just as that Amiga 1000 had come out, or getting a preemptive Amiga 500 just as the x86 PC-compatible industry was bearing down hard on it, or getting a mind-blowing Sega Dreamcast just before the PS2 and first Xbox crushed all hope for its future (and not heeding the advice of past Saturn users, of course). All such computing tragedies happened to me, and they all created so many happy memories before the dream had ended.

I want to keep this dream alive.

Lee Djavaherian

Lee Djavaherian