This prototype translates a series of small side-to-side head movements into electrically "pressing" a button. It was built to support a family member with late stage Motor Neuron Disease (ALS) who was having trouble pushing a physical call button for attention in the night due to deteriorating mobility in their hands and arms.

The family member says this device was "life-changing" and improved their sleep quality significantly — no longer needing to hold awkward, unreliable poses to shift weight onto a button with the little strength they had. At the time of writing in Jan 2026, the device has been reliably in use for 11 months. It has survived daily handling by carers, is insensitive to placement, easy to aim, and simple to use. An external battery backup unit keeps the sensor operational in a power cut.

Further iterations on this concept could be much smaller and tidier, but I'm pleased how well this prototype built from parts on hand has held up. This is the kind of device you definitely hear about when it's not working, and I've received very few calls.

⚠️ It's important to clarify that the existing call button was not a medical device. A state-funded accessibility organisation had taken an off-the-shelf wireless doorbell kit and wired a low-force button into the remote trigger — the chime unit placed in the bedroom of someone else in the house

Full write-up coming soon.

How it works

An ESP8266 collects measurements from a VL53L0X laser distance sensor, applies smoothing to remove noise, and looks for oscillation in the signal above a minimum magnitude. When the required number of peaks are detected, an optocoupler is used to "press" the external door bell remote button by completing its path to ground.

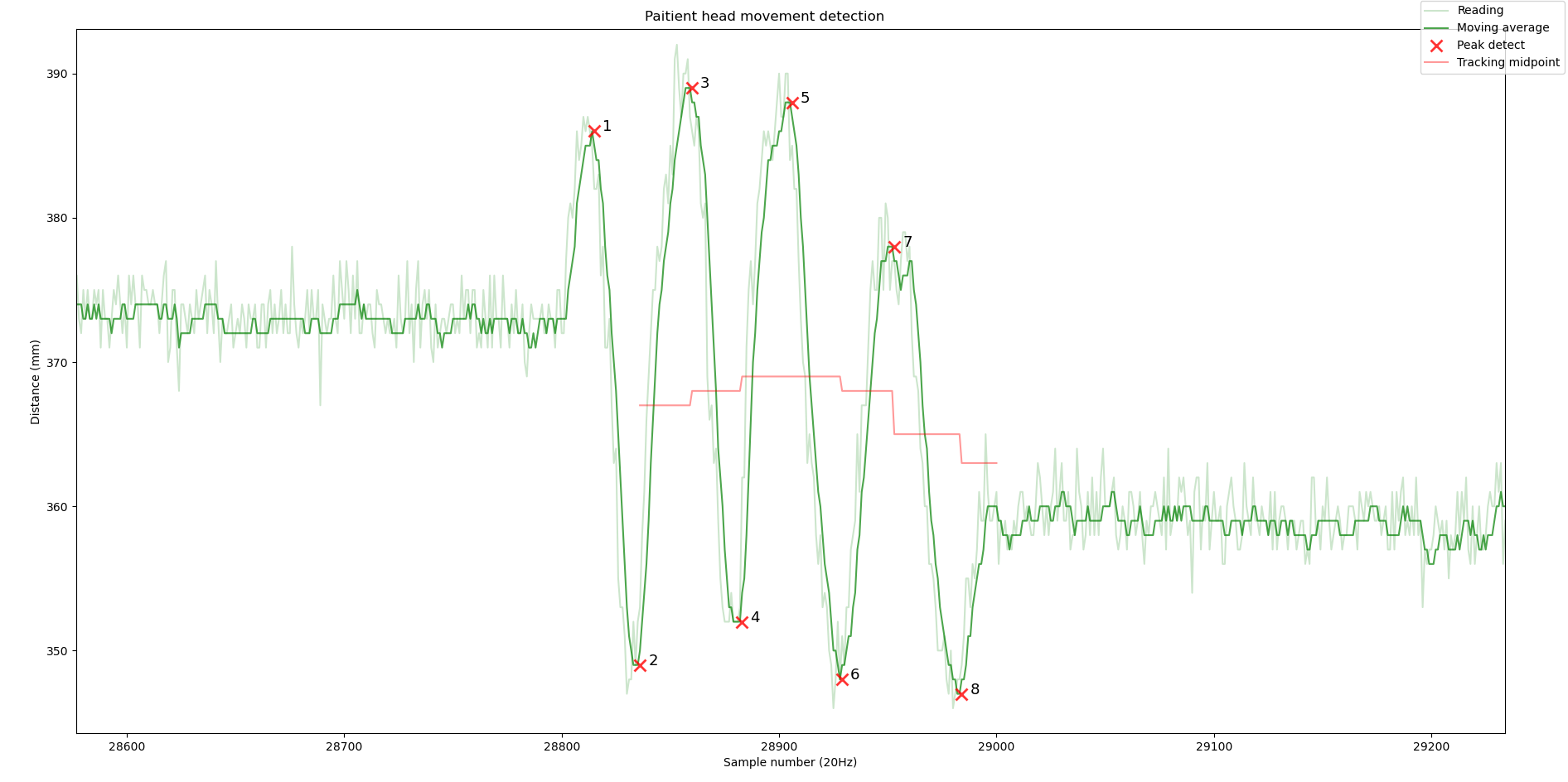

This approach achieves a strong signal, even with only a few centimetres (~1 inch) of head movement:

Peaks 1 and 2 are tracked silently. Peaks 3, 4 and 5 produce an audio-visual cue, and peak 6 rings the external door chime. Peak detection resets after a number of seconds, allowing the user to cancel a sequence by holding still.

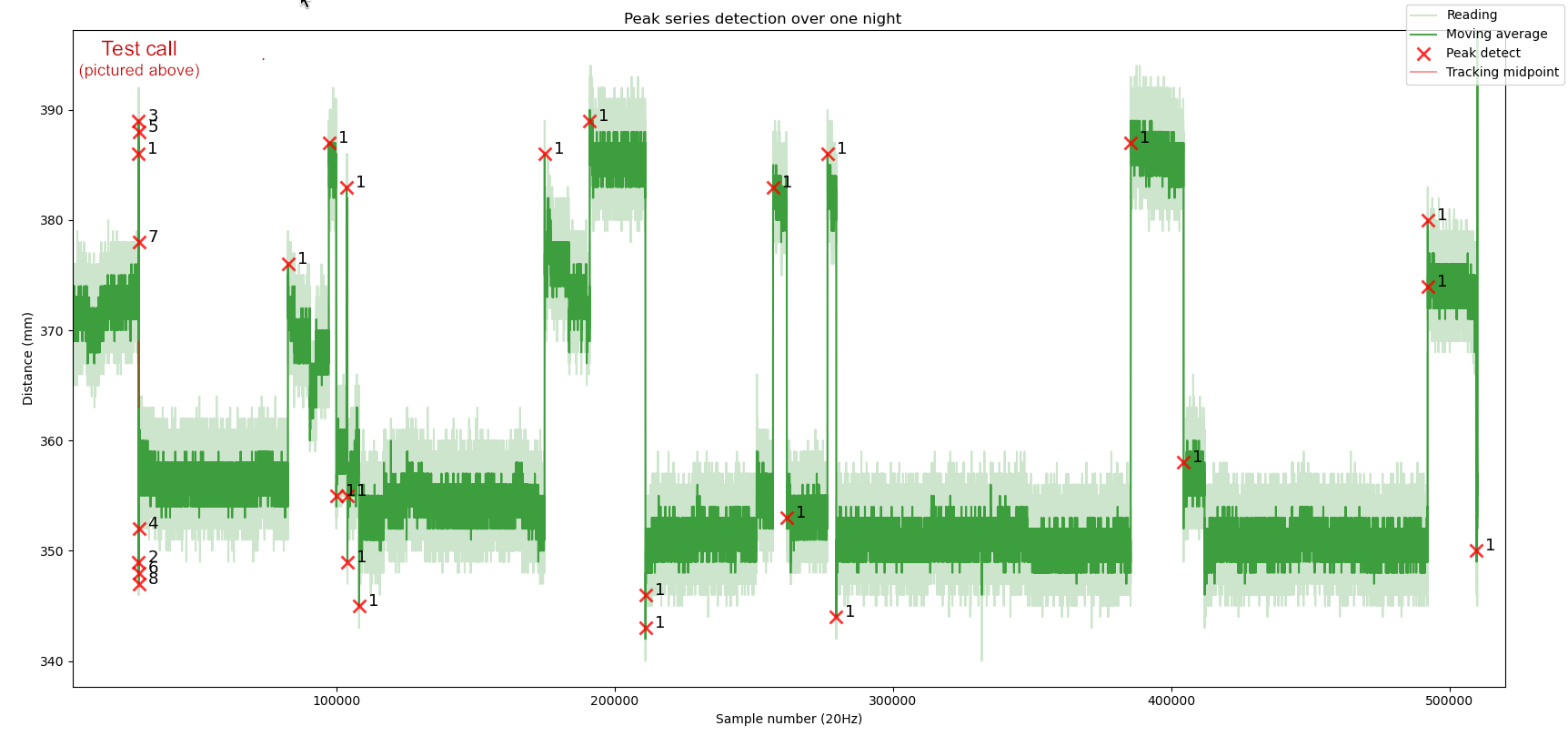

This setup allows for normal movement during sleep. Over the course of a night, re-positioning is detected, but does not form a sequence:

Over more than 300 nights this has never produced a false alarm, but is easily set off by the user when they intend to.

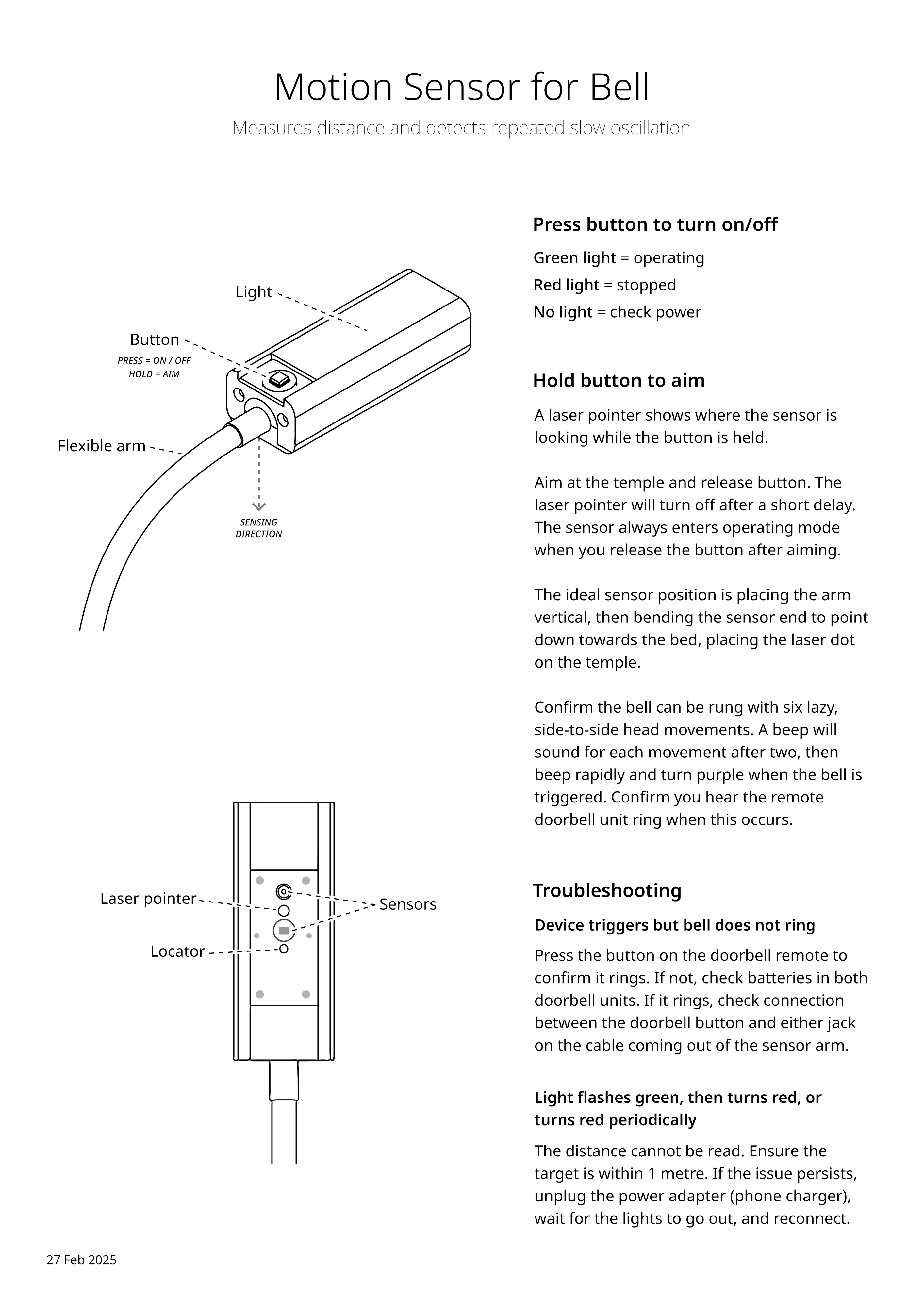

Operation by staff

The device was designed to be robust and simple enough for a team of care staff to use and handle daily. I produced this help sheet to go on the wall by the bed:

Process and back story

Exploring this person's range of motion, we had identified head movement as their strongest signal. Speaking was muffled and complicated by noise from a BiPAP (breathing) machine. Blinking and eye movement were possible, though more complex to measure. Other motions were limited or tucked under blankets at night, making them harder to work with.

Sensing needed to work reliably in the dark, and any solution needed to be sturdy and simple enough for multiple care staff to use daily. I considered various options including camera, radar and sound based systems, but eventually settled on infrared laser distance measurement for its simplicity, precision, fast response time, and non-contact nature. I paired this with a non-contact infrared thermometer to keep options open — since I live in a different city, the most practical approach was to build a field-ready prototype, then install, test and tune all in one trip.

Like many of my projects, this started with human-centred design in writing: understanding what operators and the patient each needed, how the device should behave to meet those needs, and how the device could communicate with each party to close the loop. A week of frenetic evenings of mechanical and electrical design, kitchen bench fabrication, assembly, debugging and re-assembly later, I had a reasonably robust unit built from parts and materials on-hand. The FreeRTOS firmware for the ESP8266 inside took a further week of evenings to put together. There is no escape from integration hell, but in this project I managed to squeeze in just enough provision for change to avoid starting over at any point.

The core electrical function of the device is an optocoupler used to "press" the external door bell remote by completing its path to ground when commanded by software. The rest of the hardware includes a VL53L0X laser distance sensor and MLX90615 non-contact thermometer, several LEDs, a buzzer and a red laser diode for aiming.

Initially the detection algorithm was a beam-break style trigger using a combination of temperature and distance readings, however testing with the family member quickly revealed this approach wasn't going to work. When lying in bed their head movement range totalled only a 4-5cm (1-2") side to side, with all of these positions being normal during sleep. No abnormal positions meant beam-break was out.

After some overnight sensor data captures, further thought and offline testing, I changed the detection algorithm to find oscillation in the distance signal — triggering the bell after a series of lazy side-to-side head motions. One or two head movements could be silently ignored, three or more give a warning the bell will be rung soon, and on the sixth peak the bell is triggered. This worked well reliably enough that the device was put into service immediately with this algorithm, quickly replacing the physical call button.

Stephen Holdaway

Stephen Holdaway