BACKGROUND

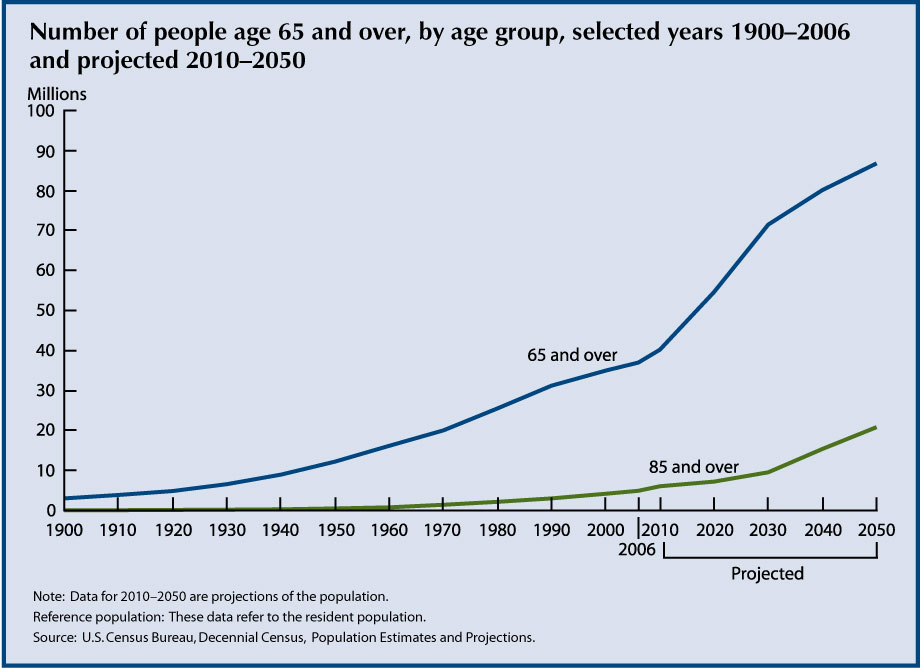

By 2030, a quarter of the population will be over the age of 65. Though life expectancy has increased significantly over the last century, complications from chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, osteoporosis, and cancer often cause catastrophic events in the elderly - leading to functional decline, loss of independence, and even death.

Our team had the opportunity to shadow and work with the geriatric population the last two months in the Miami Veteran Affairs Hospital as well in the Miami Jewish Health System, a private healthcare facility for the elderly. We learned that the holistic treatment of the geriatric population addresses four domains: medical, psychological, socioeconomic, and functional. The last domain, functional, describes the ability of an individual to live independently.

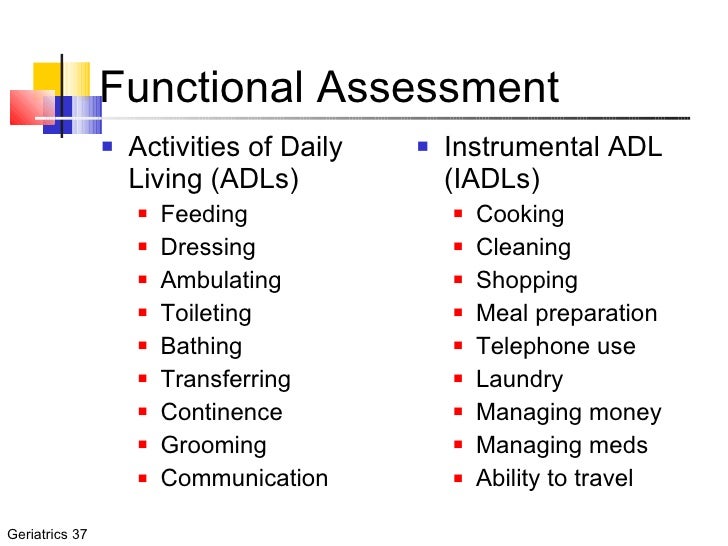

To assess independence, doctors evaluate a patient's ability to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Livings (IADLs). These tasks - eating, dressing ourselves, bathing, making phone calls - we perform every day without a second thought. However, to patients recovering from catastrophic events, these tasks may seem insurmountable.

Patients who cannot perform any of the ADLs or IADLs cannot live independently in the community and depend on nurses, aides, and social workers. These individuals often have to move from their homes to assisted living and long term care facilities, at times against their will (for their safety).

After identifying and screening many potential healthcare needs of this population, we discovered that inability to transfer independently was one of the largest contributing factor to loss of independence among the elderly. Recovering from a heart attack or a bout of pneumonia, these patients are often decompensated and at a very high risk of fall. Consequently, they remain bedbound, leading to further decompensation and further loss of functionality. These patients have higher rates of mortality due to increased risk of pressure sores and infections. After witnessing this happen to many of our patients, we decided to take action.

IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

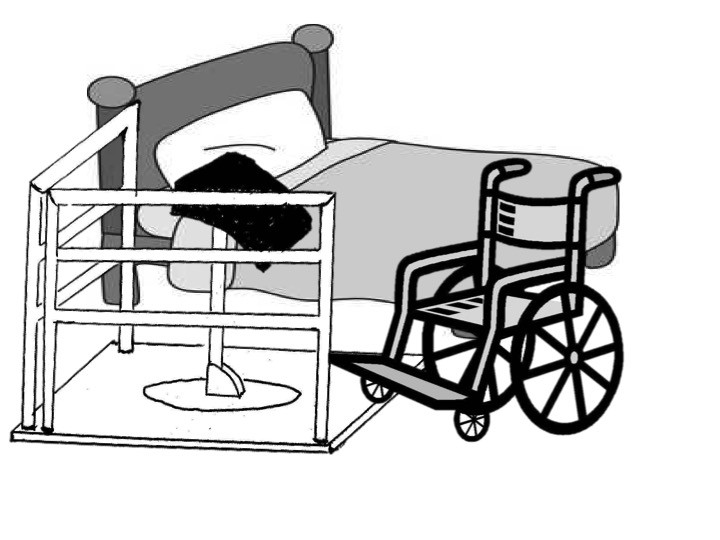

Rehabilitation medicine plays an essential role in helping individuals recover from acute illnesses. Physical therapists and physical medicine doctors work tirelessly to help patients become more functional and more mobile. One of the most important milestones a patient learns is the ability to transfer from the bed to the wheelchair. This is a key milestone in recovery for bed-bound patients. The ability to travel in a wheelchair exponentially increases a patient's functionality. They can now eat in the kitchen, bathe in the restroom, and better interact with their loved ones.

Use of a Hoyer Lift (image courtesy of Free Foundation)

Patients unable to transfer into a wheelchair require expensive hoyer lifts (essentially cranes operated by an assistant) or use a transfer board (essentially a wooden board that an assistant slides the patient on). It is important to note that some patients can use these independently, however this requires immense arm and wrist strength that many do not have.

Use of Transfer Board (Image courtesy of Fairview Health Services)

We decided to create a better assistive device that patients can use to reliably transfer from bed to wheelchair and back. Our device is geared toward patients with limited upper and lower extremity strength.

OUR SOLUTION

To create our device, we observed our patients, interviewed physical therapists, and actually performed hundreds of transfers on our own using the existing transfer board and various prototypes. We discovered the simplest movement for a chair bed transfer was not a lateral slide (such as the one the transfer board uses) but rather a pivot of the body. This movement is captured with our first prototype which we created with a pair of crutches.

USE:

- The wheelchair is parked parallel to the bed, right behind the device.

- The user places his feet on the pivot disc, and shifts his weight forward onto the chest pads.

- The user then twists his body, which is facilitated by a pivoting disc.

- The user sits down, completing a safe bed-chair transfer.

Positioning of the TurningPoint device, wheelchair, and bed.

Explanation:

- The platform allows the whole apparatus to be completely stable which maximizes the use of user's strength and also minimizes falls. Additionally, it allows the user to wheel their wheel chair right up against the chest pad.

- Leaning function: The chest pad is designed to lean-in closer to the user to facilitate the user to lean on to the chest pad while seated

- Pivot function: The chest pad is also designed to stand up-right, effectively transfering the user's weight on to the chest pad. Once the weight is on the pole which sits on the rotation table, it is very easy for the user to pivot around to the bed or the wheel chair

- Adjustable pole: Depending on the user's height, wheelchair height and the bed height, the height of chest-pad-pole can be adjusted accordingly.

![]() Top View

Top View

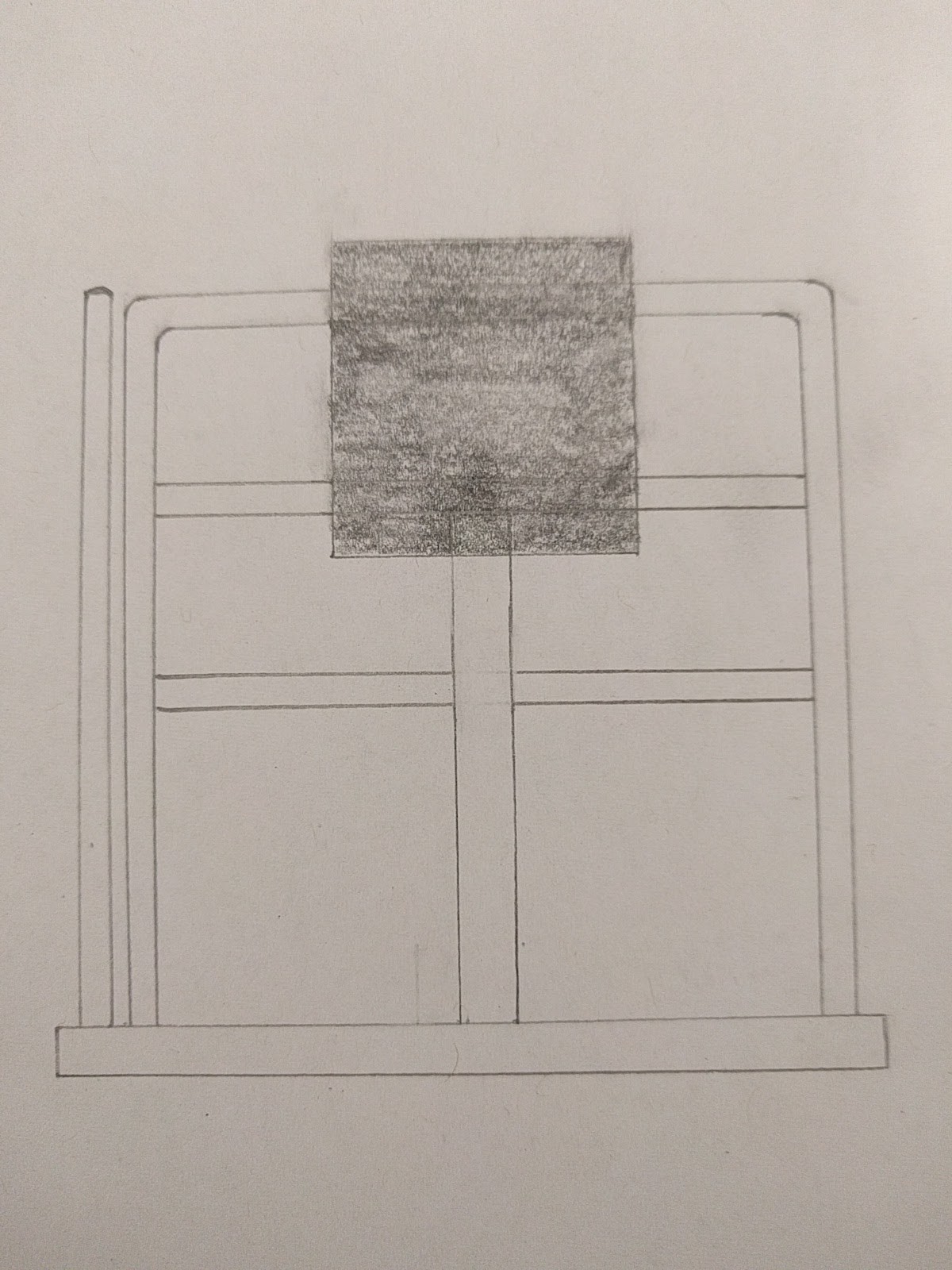

![]() Front View (Wheelchair Perspective)

Front View (Wheelchair Perspective)

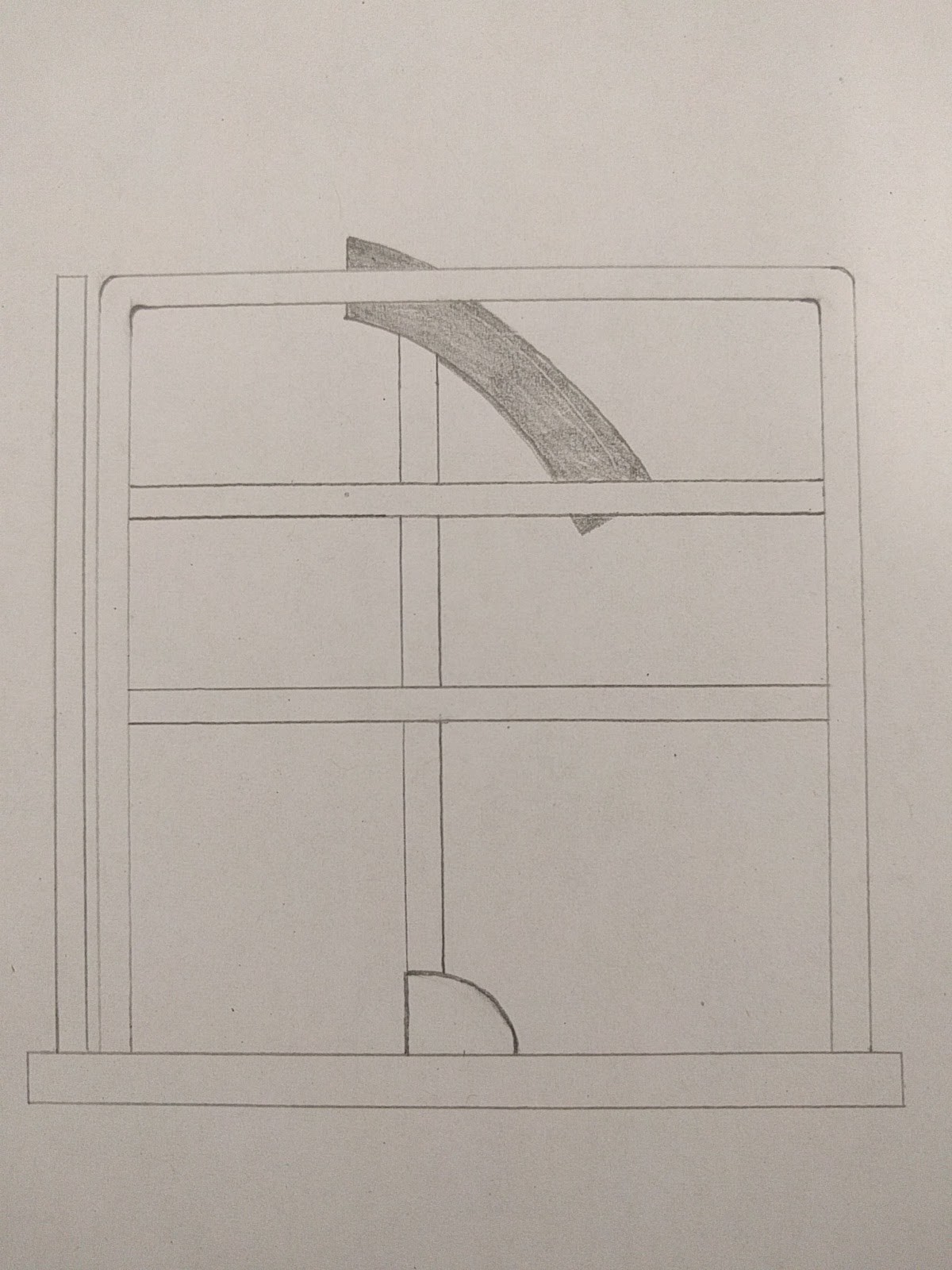

![]() Side View

Side View

ADVANTAGES

- Less strength required. The leg muscles are naturally used in the process of standing and transferring. With our device, the user does not need the ability to completely stand. He or she only needs to be able to transfer his weight onto the chest pads.

- Less risk of falling. The chest pads and railings provide multiple levels of support, allowing the user to confidently transfer without fear of falling. The fixed pivot disc provides more stability than a free standing one.

- Less painful. A large issue for the transfer board was the strain on the wrist and hands required to shift the weight laterally. The chest pads and the turning motion resolves this issue completely.

- Low cost. The current solutions on the market (such as the hoyer lift or transformable wheelchairs) can cost thousands of dollars. This device can be made for less than 50 dollars.

- Easy implementation: This device does not require any additional modification of the bed or of the wheelchair. It can be quickly installed.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

- Build. Refine. Repeat. Our most basic prototypes function well, proving that validity of our concept. We plan on continuously refining and improving our device until we can accomplish our vision.

Louie Cai

Louie Cai Top View

Top View  Front View (Wheelchair Perspective)

Front View (Wheelchair Perspective) Side View

Side View