What is a scanning probe microscope?

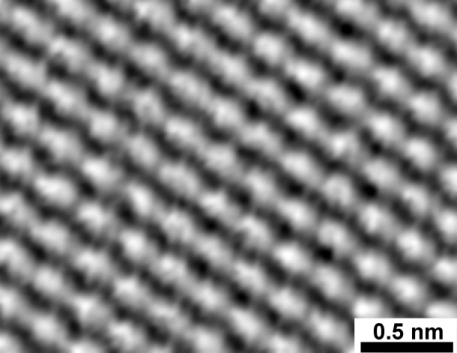

It's a microscope that builds images of physical things by poking them in lots of places with a probe. Instead of illuminating a specimen with photons and then collecting the ones that bounce back all at once with an image sensor, a scanning probe microscope (SPM) collects the measurements it needs in order to give you an image one by one. While this approach sounds like a step backwards (maybe a throwback to the first scientific instrument - the poking stick), it actually provides many very cool benefits. For example, your resolution is no longer limited by the diffraction limits of light so it is possible to take images of really small things, like atoms! Here are carbon atoms in graphite, as imaged by a scanning tunneling microscope (a type of SPM):

Big benefit #2 of SPMs comes from the fact that you can get really creative with the probe. The image above was generated by measuring the tunneling current between an electrically conductive tip and the sample of graphite. But a different type of microscope, the atomic force microscope, generates images by measuring how much the sample deflects the probe at each point. That is, it measures the force that the atoms exert on the probe at every point in the area of interest. Other probes are designed to measure heat, capacitance, chemical nature, or a host of other properties. This makes SPMs an extremely flexible tool for doing science on a small scale.

The last major benefit is that SPMs are not limited to just looking at very small things - they can make very small things too. To see how that can be, imagine the probe as the cutter on a CNC mill. By allowing the tip to interact with what is under it the SPM can be used to precisely modify nanostructures. For example, IBM famously used one to write their name in xenon atoms on nickel in 1990:

Why?

A great deal of cutting edge research nowadays in many fields, like microelectronics, biology, and material science to name a few, are only possible thanks to scanning probe microscopes. They, along with a handful of other instruments, are the Swiss Army knives of nanotechnology. I believe that a great number of our achievements as a species this century will trace back in part to the fantastical ability of SPMs to precisely measure and manipulate matter on the atomic scale. As a result, I believe that their commoditization would accomplish two great aims: 1) Lower the barrier of entry for development of nanotechnologies. 2) Speed our progress towards further technological revolutions.

How?

Scanning probe microscopes are generally extremely expensive instruments found at universities, only operated by crufty ex-industry engineers or twitchy, sleep-deprived PhD candidates. Making them cheap enough to show up on the desks of hackers and makers seems infeasible. But there are good reasons to think it can be done:

- It has been done before, multiple times and by different people. But not yet in a robust, reproducible way that would have direct impact in science and engineering.

- Lasers, optics, microprocessors, sensors, and analysis tools are all free or cheap these days. The design of Automatic Jack leans heavily on the great resources that have been brought to bear in mass-manufacturing of high technology goods.

- Modern computer-aided rapid manufacturing makes putting the pieces together much easier and improves the reproducibility of designs.

Challenges

- Touching individual atoms takes structures on the order of individual atoms. Whether they are physical probes or light waves, they need to be infinitesimal.

- To get atomic-scale data from probes takes mechanisms and electronics of great finesse. Atomic force is measured in probe deflections of tens of angstroms and tunneling current is in the range of pico or nano amps.

- A probe interacting with a single atom returning clear data above the noise is an exciting achievement, but to do useful work - imaging or manipulation - the probe must visit other atoms. So it must be moved precisely in subatomic increments.

- Our everyday, macroscopic world may sometimes feel chaotic. But by nanoscopic standards it might as well be considered standing still. Noise is a huge problem in the way of taking measurements of atoms. Without proper isolation any small motion will completely swamp your measurement. Even the truck idling outside your building is a catastrophic cacophony.

Approach

The challenges standing in the way of realizing cheaper instruments like this are extremely vulnerable to a hacker mindset. Many have already made this observation and thanks to them there is already a body of pre-existing hacks to build upon, which I'll do my best to collect into one place in the files attached to this project. The hack that started me down the road to this project occurred to me when I was taking apart a stack of CD drives that I had pulled out of the trash. I realized that these common devices which someone had just thrown out could read millions of ~800 nm dots per second. In the eyes of a hacker any optical drive is a powerful microscope. In particular they are an example of a particular type of microscope, a confocal microscope.

Optical Drive Confocal Microscopy

In a confocal microscope the light used to take the image is sent through optics that make it into a minute spot on the specimen. Then the light is scattered and some of it returns along the same optical path, back towards the light source in the microscope. A beam splitter redirects this light to a sensor. By moving the spot of light across the specimen an image is slowly built up. The advantages in this approach are increased spatial resolution, better contrast, and the ability to image in 3D by changing the focal depth of the spot of light.

Nearly every optical drive in existence today is a veiled confocal microscope of impressive resolving power. They are configured to make sense of dots on a disc, but it takes no great leap of imagination to see the possibility of modifying them to generate images of arbitrary small stuff. Plenty of people have seen the connection over the years and have come up with many microscopes based on off-the-shelf optical drives []. Unfortunately the concept has never spread very far, for a variety of reasons.

A confocal microscope built from a Blu-ray drive gives us leverage into the hundreds-of-nanometers scale, but you are not going to see atoms with one. How do we get the rest of the way? We do it by getting more leverage with another hack.

Optical Levers

Maybe hack is the wrong word for this one because it was developed at IBM by professionals with plenty of resources. But it still feels like a hack to me because it is an example of incredible power drawn from simple phenomena interpreted in a fresh way. Atomic force microscopes (AFMs) generate images by poking atoms with a tiny needle and measuring how much the atoms push back. The atoms only push with a few piconewtons of force, so how can you possibly build a machine able to see the resulting deflection in your probe? The answer is exploitation of optical levers.

On a lab bench, take a laser and point it at the mirror on top of your probe (called a cantilever in the context of AFMs). The light will bounce off and continue on until it hits a wall or ceiling. Now touch the probe so gently that you are not able to see it move. Do it again but watch the laser spot on the wall. Even though you cannot see the probe itself move, the laser spot will likely move a few centimeters or more. That is the power of an optical lever. Just replace your eyes with an image sensor and your finger with something able to move in subatomic increments and you have got a machine able to measure how much atoms value their personal space.

Jack does not use a naked laser beam for the optical lever. Instead, it will use the weirdly shaped beam of light that comes out of a hacked optical drive head. As a result the sensing stack doesn't need as much space as an optical lever needs for its beam movement, just around a centimeter.

Subatomic Scanning

Measuring the interaction of the probe with a specimen is relatively easy compared to the scanning part of "scanning probe microscopy". All of the regular mechanisms for obtaining precise linear motion break down on the atomic scale. Screw drives, linear bearings, stepper motors, servo motors, etc. that people are familiar with from 3D printers produce terrible, jagged motion on the nano and sub-nano scale. And they completely lack the ability to move in subatomic increments. So common motion systems won't work in this context and a fundamentally different approach is needed.

Similar projects that I have been able to find in my research have all used one approach: modified piezoelectric buzzers []. Piezoelectric materials are defined by their ability to translate between mechanical stress and voltage. Buzzers based on such materials are found everywhere, from your microwave to your watch. They are dirt cheap and readily available from your favorite electronics suppliers - another one of those technologies that seem boring at first but will take you by surprise from the right perspective. Piezoelectric buzzers can move in precise subatomic increments. They basically turn the problem of subatomic scanning into building a sufficiently precise voltage driver, a very well solved problem [].

But Automatic Jack will not primarily use piezoelectric buzzers for scanning. Why? Principally because piezoelectric buzzers are too limited in their range of motion. They can move in subatomic increments, but only over around 10 microns of travel. Many applications I foresee for Jack lie outside of that range, such as silicon reverse engineering and watching specimens in cell cultures. Another technique is needed to form a hybrid with piezoelectric scanning in order to form an overall system able to do useful work from millimeters down to angstroms.

Happily inspiration for the solution can be found in one of the previous hacks. Optical drives contain many basic optical components, such as dichroic beam splitters, lasers, and lenses. For their focusing they use very fine voice coils which are perfectly capable of moving in sub-micron increments in order to make the laser dot the right size to read the disc. Separating these parts and recombining them allows for a system that can move across several millimeters with nearly nanometer accuracy and precision.

The trick is in exploiting optical interference. Details will come in later posts, but the gist is that Jack's primary scanning stage will be composed of two Michelson interferometers (one per axis) built from optical drive parts. Light sensors will measure the interference and after some conditioning that signal will be read by the quadrature encoder built into the microcontroller coordinating the scans to obtain position in tens of nanometers.

Closed-loop control will make nanometer positioning of the sub-nanometer scanning head feasible, but still does not resolve the problem of linearity in the overall motion. Knowing where you are to within ten nanometers is no big help if you cannot reliably get to other places because you are riding some bumpy linear bearing.

My cheap work-around is to get rid of sliding surfaces altogether. The scan head will be supported by an XY linear flexure. My hope is that this can be cut out of plastic by a laser cutter, but it may be necessary to water-jet cut it from metal to get the right mechanical properties.

Very Sharp Probes

To poke atoms we need something on the scale of atoms. So we need a very sharp needle with many special properties. Thankfully others have solved this problem in mostly satisfactory ways. One way is to take a bit of tungsten wire and carefully electroetch it until it has an atomically fine point. Another way is to slowly pull ductile metals like copper until they break. Or one can buy real AFM tips for several hundred dollars per pack (not really an option).

What's in the Name?

Automatic Jack was the hardware hacker from the pair of hackers in William Gibson's Burning Chrome.

I was working late in the loft one night, shaving down a chip, my arm off and the little waldo jacked straight into the stump.

The waldo looks like an old audio turntable, the kind that played disc records, with the vise set up under a transparent dust cover. The arm itself is just over a centimeter long, swinging out on what would’ve been the tone arm on one of those turntables. But I don’t look at that when I’ve clipped the leads to my stump; I look at the scope, because that’s my arm there in black and white, magnification 40x. I ran a tool check and picked up the lazer. It felt a little heavy; so I scaled my weight-sensor input down to a quarter-kilo per gram and got to work. At 40x the side of the program looked like a trailer truck.

Owen Trueblood

Owen Trueblood