-

Diving into Alice’s PID controller ( mood = nerd; )

04/09/2021 at 18:15 • 0 commentsAlice’s locomotion algorithm consists of a Finite-State Machine (FSM) that sets the desired kinematic trajectories for each motor. Once the kinematics in the form of joint angles are defined, PID speed regulators are activated controlling the motors’ speeds to move from the current position to the objective joint angles.

Figure 1. Block diagram of the controller, digital filters implementation and data acquisition.

The angle of the motors is indirectly obtained through potentiometers installed in the mechanical system. A mathematical mapping was constructed to convert the potentiometers’ voltage measurements to angles.

The speed is estimated through a second order approximation of the derivative. In addition, discrete third order Butterworth filters were designed and implemented for the angle and speed variables. The cutoff frequency of the filters was designed to be half the sampling frequency to avoid aliasing and still be able to recover signals within the desired spectrum, according to the Nyquist sampling rate.

Figure 2. Angular velocity (blue) with the motor in static state, and filtered velocity (red).

To calculate manipulations, the derivative of the error was computed using a second order approximation and a Butterworth filter was applied to them using the previously mentioned cutoff frequency. Additionally, an anti-windup incremental algorithm was used to saturate the Integral action of the PID, and general non-symmetrical saturations were also implemented over the total manipulation computed by the controller. Finally, constant non-symmetrical tuned values were added to the PID’s manipulations to decrease the effect of the dead-zone nonlinearity created by the static friction of the motors.

The following graph shows the efficacy of the control algorithm in achieving target speeds while alternating joint-movement direction.

Figure 3. Performance of PID velocity controller with different target speeds and during alternating motion. For slower speeds, velocity is maintained during longer periods of time; reaching time is also longer.

-

How we made our materials more resistant on a low budget.

03/19/2021 at 21:42 • 0 commentsWhen trying to find the balance between low-cost and strong materials we did some research about how we could make our 3D printed parts just resistant enough. We had heard about Carbon Fiber and thought about giving it a go. We studied the process and quickly realized it was a bit complex for us. We wanted to skip the molds and find an easier way. Maybe covering 3D printing parts?* After several attempts, we finally found the best way to do it. Now we’d like to share it with you.

- Keep in mind that Carbon Fiber sheets can be harmful to the skin, so it’s important to dress properly. You will need to cover every visible part of your skin so we recommend you wear gloves, a face mask (covering nose and mouth), glasses, and a coat.

- After you dress up and get your Carbon Fiber ready, we recommend you measure the pieces you want to cover and draw the area you need on the fiber marking it with tape. Use a penknife to cut the area, the tape will help to get the little fibers that form the sheet to stay together when you cut it.

- Prepare the epoxy resin following the indications of the specific brand you bought (the one we use requires 2 parts of resin and 1 part hardener solution). Take into account that the mixture starts getting hot minutes after combining (20 min for ours), so you need to make sure to work fast and to mix only the amount you will really use. We recommend buying from polyestershoppen.nl or getting West 105 + 205 epoxy resin and hardener.

- When you have your epoxy ready and the Carbon Fiber cut to size, we recommend you cover both sides of the Carbon Fiber sheet with epoxy. Afterwards, place it on top of the PLA part you want to reinforce. Add a bit more epoxy on it and make sure it touches the whole surface so that no bubbles are formed. We recommend reinforcing one side at a time.

- Let it rest for a whole day and after 24 hours you may cover the other side if needed. Make sure you don’t move or touch it while it’s drying to avoid leaving unwanted marks. After every side has been covered and the part has completely dried, you can now cut the excess and give it its final shape. We recommend using a Dremel or a similar rotative tool. Make sure you protect your skin, eyes, and mouth especially for this part. Carbon Fiber particles can be really sneaky and they itch a lot, potentially causing important problems in your lungs if you let them in, so make sure you take this warning seriously ! If you can work outside that would probably be better; try using a box or a bag as well to collect all of the dust.

Hope you liked our mini tutorial, If you have any suggestions or additional questions do let us know ! We are sure there’s room for improvement.

Remember you can build your own exoskeleton with us. Follow the link for more information in our website: http://www.indi.global/alice

* This idea came originally from Jeff Gorges at the University of Houston.

-

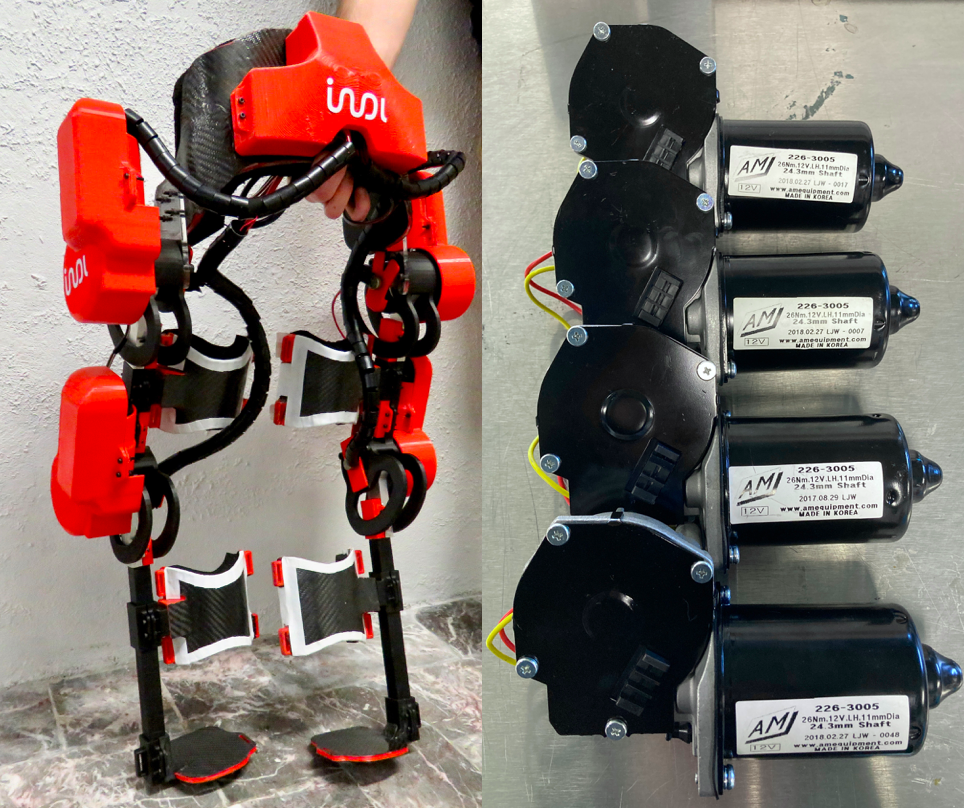

Talking Motors

02/19/2021 at 18:00 • 0 commentsDuring the building of the pediatric exoskeleton, some actuator evaluations were done in order to decide for the best option. The state-of-the-art Brushless DC motors by Maxon Group (Switzerland) joined with strain weave gears by Harmonic Drive LLC (United States) combinations were compared to DC Motors by SIEMENS (Germany) and AM Equipment (United States). Even though the state-of-the-art combination is undeniably better in performance, both SIEMENS and AM equipment 26Nm DC actuators were found to be appropriate exoskeleton implementations.

AM Equipment DC actuators were finally deemed the best option for continuous system production and deployment due to technological characteristics, price and overall product availability within the Mexican market.

Four actuators were used and covered hip and knee Degrees of Freedom; this reduced complexity and weight while maintaining minimum functionality required for standing and walking tasks.

We have been searching for different alternatives and similar motors to make sure people outside The US and especially in Europe have easier access to low-cost actuators but we haven’t been able to find other suppliers with similar options and reliability. Let us know if you find any !

![]()

-

Open-Loop and Closed-Loop control

02/05/2021 at 22:31 • 0 commentsOn the first version of Alice, in order to ensure user's safety, we opted for an incremental approach in the control scheme. Because of this we decided to start with a very simple control system that manipulated every step separately, instead of a complete routine.

This control scheme consisted of an Open-Loop strategy to minimize the risk in case our sensors failed. In the newest Alice version we have made improvements to ensure robustness on sensors and a good signal quality through digital filters. These changes allowed us to increase the automatization of Alice’s movements through a Closed-Loop algorithm (PID), replacing the Open-Loop strategy. This whole process resulted in 3 different functions: stand-up, walk through 4 movements and sit down.

The PID control scheme was designed and integrated using potentiometer-based feedback referencing joint angles in real time. Third-order Butterworth filtering, anti-windup algorithms, and static friction compensations were implemented to account for potentially larger amounts of noise, mechanical resistance, and overall system nonlinearities. Controller tuning is analogous for the left- and right-side actuators; position mapping parameters are set individually per joint.

![]()

To maximize the access through Open Source platforms, the whole control algorithm was implemented on Arduino, creating some custom libraries. We believe that this will allow more people to implement it; however, we are getting to the maximum memory available on Arduino. Following upgrades should consider memory optimization.

-

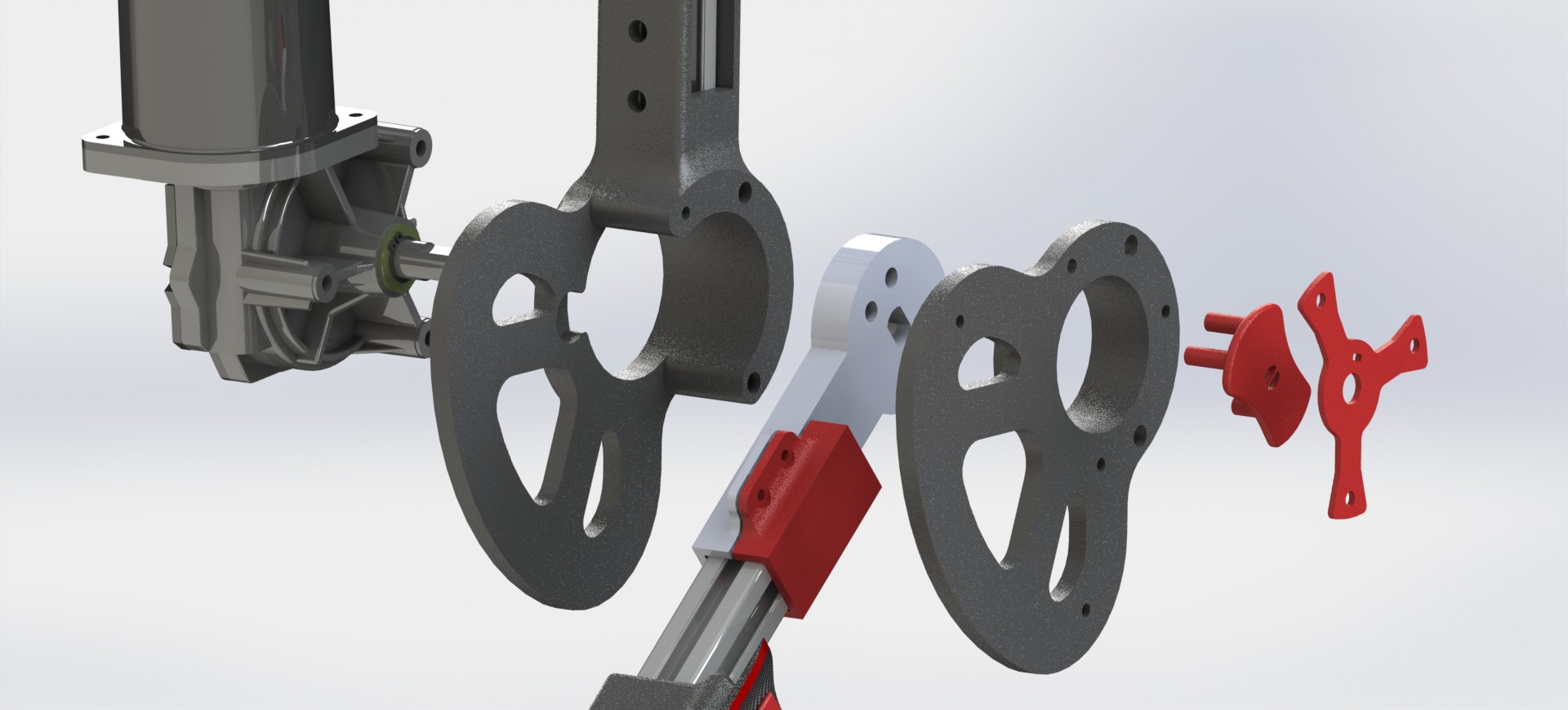

Material Evolution

01/30/2021 at 00:09 • 0 commentsOne of the most important evolutions undergone was focused on the joints, which are the unions between the motor and the profiles transmitting the movements to the legs. These unions were constantly getting broken when mechanically-demanding movements were performed. Throughout the years some partial solutions for this problem have been tested focused on local manufacturing, considering limited budgets, in order to find the right design, components combination and operation conditions.

Aiming to maximize the material resistance, while keeping the manufacturing process simple, we started using 3D printed pieces on PLA for the first iteration, (although we suspected the resistance would not be what we needed) because we knew it would still provide valuable information to move forward. This material was later replaced with Aluminum but it was found to be very expensive to make all the parts out of this material. The next material candidate we tried was Nylon + Carbon Fiber, which merged the advantages of PLA and Aluminum, but its sensitivity to humidity and abrasiveness were too high. Finally, we came up with the best solution (so far): ABS + Carbon Fiber. One of the nice properties of this material is its low plastic deformation and abrasiveness together with its humidity resistance; additionally, it profits from a nicer finish.

Because of the nature and difficulties that 3D Printing presents, it seems like iterations and manual destruction are not only a practical approach but maybe an appropriate process in finding the desired balance between manufacturing process and material resistance.

We can currently advise you to use ABS + Carbon Fiber, but please let us know if you find something else which might work even better!

-

The Open Source Program

01/22/2021 at 22:08 • 0 commentsSince the beginning, our aim was to create as much -real- impact as possible. Any Pediatric Exoskeleton is already a big deal which can surely benefit many children, but we couldn’t stop thinking that even if prices were accessible, there would always be someone we wouldn’t be able to get to.

We decided to propose an Open Source Model paired with a Sharing and Collaborating Program to ensure that the design wouldn’t just go into a repository where people wouldn’t really know what to do with it. An exoskeleton is a complex machine which can really make use of a bit of instruction and support in order to be successfully built and run. We want to help makers around the world really get into the technology, and we want to push collaboration beyond our own capabilities as well!

Because of the children-focused nature of Alice, and due to the fact that it operates with high levels of current with moving parts which could very well damage someone’s limbs if not operated properly, we provide free access to the codes, designs and reference material after a screening process which ensures only people with basic engineering experience and aptitude attempt to build and use the device. We want to make sure Alice helps children, and we want to make sure nobody is damaged through what we have made.

If you want to build your own exoskeleton, make sure to request full access through this link.

We have a growing community in Italy, Greece, the USA, Chile, México, India, Ecuador, and more; and we would love to have you with us!

See you there and until the next log! :)

-

Clinical Success and our Golden Pilot

01/16/2021 at 09:33 • 0 commentsOur pilot was born with Muscular Dystrophy; unable to move his legs. This forced him to depend on wheelchairs and brought additional complications spanning body and mind. Unable to walk on his own, independence became something unusual for him.

In 2018, his grandmother heard of our project but our exoskeleton was not ready for him. We asked them to wait so we could be sure that Alice would be safe enough for him to wear. His grandmother was patient -yet insistent- and wrote back to us every month for the next ~12 months. After about a year of testing, detailing, and getting the appropriate clinical permissions, we were finally able to give them some good news.

![]()

In 2019, he made a first attempt at standing up and walking with the help of Alice, but he didn’t manage to do it. On his second try the day after, however, he was able to stand, walk, and wave for a photo without the help of anyone else.

This was an important day for the team, because we proved that Alice could indeed support children with high disability and up to 50kg + ~1.4m… but it was way more important because it made us feel that what we were doing could actually achieve something significant for others. He was one of 10 children who participated within our first user tests.

-

We are back !

01/05/2021 at 17:46 • 0 commentsSince the last post, a lot has happened. We have moved from the early prototype we showed you in PLA to a still-simple but patient-compliant clinical device; and we definitely want to keep sharing it in Open Source with you !

During this time, we have created new designs, new codes, and new electronic / mechanical combinations which have made it possible to even test a couple of prototypes in hospitals so we can now say that Alice has been validated with patients. We have also been working on creating and growing an Open Source program to help more people make their own exoskeletons. You can also bet we have been drinking lots of coffee during the whole process.

We know it has taken us a while but we can finally sit down and write about it, so we will soon be uploading more posts to tell you some of things that happened during this process and to share all of the details you need to know to make your own patient-validated exoskeleton.

Stay tuned, we will be trying to make a new post every week !

PS: Here’s a sneak peak of the use of Alice with patients.

![]()

Alice Open Source Exoskeleton 2021 Update

Open Source, Child-Focused Leg Exoskeleton for accessibility in developing communities.

Jesús Tamez-Duque

Jesús Tamez-Duque