Reverse engineering the Rotor

The Rotor, an Italian public payphone introduced at the end of the '80s, was never defeated by phreakers; trying to change that

The Rotor, an Italian public payphone introduced at the end of the '80s, was never defeated by phreakers; trying to change that

To make the experience fit your profile, pick a username and tell us what interests you.

We found and based on your interests.

cpu_ram_schematic.zipCPU and RAM board schematics (EAGLE format)Zip Archive - 213.98 kB - 10/20/2021 at 08:24 |

|

|

hitachi_module_fixed.zipHD6305Y2 Ghidra module (copy in Ghidra's Processors folder to install)Zip Archive - 16.37 kB - 10/19/2021 at 20:31 |

|

Italiano:

Dopo lunghe ore di imprecazioni con il Logic Analyzer, conosciamo ora (con un ragionevole livello di certezza) tutti i comandi accettati dal telefono e tutti i tipi di comunicazioni telefono/TRS. Per i dettagli, consultate la documentazione in PDF presente su GitHub (vedi link nel post precedente).

Visto che, come prevedibile, la maggior parte delle persone interessate a questo progetto/ai telefoni SIP/Telecom/IPM Rotor sono probabilmente italiani, ho pensato fosse sensato riscrivere la parte della documentazione che è più "utile" dal punto di vista pratico (protocolli di comunicazione, configurazione del telefono ecc) in lingua italiana; Il documento è in continuo aggiornamento, ma potete trovare quanto scoperto finora al seguente link: https://github.com/phaseseeker/RotorRE/blob/main/doc.pdf

Sempre nello stesso repository Github trovate anche parte dei manuali originali.

Nel caso abbiate qualche domanda più specifica per la quale non sono presenti risposte nei documenti contattatemi pure su Hackaday e cercherò (per quanto possibile) di rispondere.

Note for the english readers:

I will continue writing documentation in english, and the project is not abandoned; I just have little free time available, and for each hour spent writing documentation there's tens of hours of actual research. Please be patient.

(Mandatory "I'm not dead just busy" comment)

I've got exciting views for you: I've gotten to the point where I can exchange data with the phone, reversed the init sequence, and now have a phone that is almost fully functional (as in, I can make calls with coins or cards); I also figured out how the phone talks with the card reader, and I can read the cards' contents through said reader.

However, as you can see, the info here on Hackaday is waay behind the actual progress. I'm now in the process of at least writing some kinda-complete documentation, even if this means I'm probably gloss over some details about how I got to this info. That said, the first thing I'm gonna concentrate on is the "mistery" SCL1054-V4 custom chip.

What does this thing do, anyway?

Long story short, it has three functions:

In more detail:

1) The RAM

Not much to say here. It's 192 bytes of extra RAM, mapped 0x0140-0x1FF, which are directly accessible by the phone's microcontroller.

2) The ports

There's three 8 bit ports + a 1-bit one, controlled via 5 registers:

3) Miscellaneous combinatorial logic

All the logic for mapping ports+RAM+ROM in memory is integrated in the SCL chip.

Hey, look, it's only been two months! And this time I have a really juicy update!

I finally completed the schematics for ALL boards on the phone, including those pesky "hybrid" ceramic modules! Well, almost, the one thing that's missing is the ceramic module that contains the head amplifier/analog interface circuitry for the card reader; however, its inputs and outputs are pretty easy to identify based on the rest of the schematics, so we can basically treat it as a black box without any issue. (I did think about tracing it, but it has multiple layers on the same side of the module, so there's pretty much no easy way about it).

You can find the schematics on my Github, but here's some highlights:

The pesky ceramic modules

These are the modules that initially confused me: why did they go through all the effort and cost of putting SMD circuitry on a ceramic substrate instead of simply putting it on the main board?

Turns out the circuitry on those modules is what interfaces the delicate main board logic to the outside world. Basically, some of buffer all the inputs coming from the various switches, photointerrupters and the line interface board, to protect the main board, whereas someothers contain circuitry to buffer the outputs and to drive motors and actuators.

So the reason they're ceramhic has probably to do with better isolation and/or RF shielding.

LIOD

The LIOD (card reader) is a weird beast in itself. First of all, it's designed to be pretty much a self-contained system: it's got its own power regulation circuitry (it only takes power directly from the battery) its own MCU and ROM, and any communication with the rest of the phone goes through some buffers/drivers; however, contrarily from what I suspected, it doesn't actually interface directly with the "data communications" phone line. All of its digital I/O lines go through the small "LIOD interface" board to the main board and then to the main CPU card (HOWEVER, the other connector on the LIOD interface that according to the pictures I found online is for a "debit reader", does have a direct connection to the comms phone line; I've never seen that connector used for anything though)

Also, as I anticipated before, there's an expansion connector on the bottom of the LIOD board, which on one of my readers has an 8051 plugin module plugged in. I still have to dump the internal ROM from the 8051 (if it can even be dumped, it might have protection bits set), so I'm not sure what the module is used for; I however found it interesting that said 8051 is only connected to the main LIOD boarc with a handful of digital lines, all of which go directly either to I/O ports on the main MCU (except for the two TIMER/E signals).

The LIOD also has its own custom chip, this time from ST, marked "ICWA/B22WE9335". More on that later.

Mistery SCL1054 custom chip

From the die photos, it was pretty clear that this chip contains only digital circuitry. I initially thought this handled the data communication with the phone company; however, if you look at the schematics, the comms phone line is connected, through some optocouplers and buffering circuitry, to the main MCU. The SCL chip is instead connected to a bunch of digital inputs/outputs which go to sensors/actuators and to the line interface and LIOD interface boards. So is the chip just a bunch of glue logic to interface the Hitachi MCU's address and data busses to the various digital I/O lines + the "config" ROM and the external RAM? Or is it something smarter, so to speak, that is actually handling all the mechanical section's I/O independently from the main CPU? But, then, where would be the code for that be stored? The so-called config ROM is almost empty. It might be loaded at runtime in the external RAM chip, possibly, and that would explain the weird "activation procedure" I found in one of the manuals, which talks about the need of putting the phone in configuration mode and pressing a couple of buttons every time the...

Read more »First of all, apologies for the lack of activity. Turns out reverse engineering is not all fun and games: apparently there's a lot of hours of tedious and repetitive work to do (who would've guessed, lol). University work and a general lack of time (and motivation sometimes) doesn't help, but I'm still working on this and I'll eventually get there.

So, where's the project at?

Last time I was here I told you I bought a phone. Well, here it is, in all its faded glory:

Looks bad, but it's complete and the electronics is in good condition. Here's the internals:

Sidenote: the whole mechanical section is on hinges and can be easily pulled out for maintenance, leaving you with this:

You can clearly see where the line interface, card reader interface and card reader module go. Here's the mech by itself:

So, how does all that mess of parts work?

The mechanical section is quite straightforward:

First of all, coins enter from the slot you can see in the top right, roll down and to the side and pass through the coin discriminator module (vertical PCB you can see below the main board), which performs a series of measurements on them; the metal rod you can see circled in brown controls a flap inside the discriminator module, which, when opened, makes the coin completely bypass the discriminator itself and fall straight down to the change tray. The rod is controlled by the "redial" button on the keypad and is used to attempt to clear a jam in the mech (the coin discriminator is the tightest part of the coin path, so if the user inserts anything that is not a coin it should stop there).

After being analyzed, the coin gets to the clear polycarbonate coin channel you can see all the way to the left in the first picture. Here it encounters the first "barrier" (cyan), controlled by a solenoid; if the barrier is open (default) the coin is rejected and goes down to the change tray, otherwise it gets channeled into the coin rotor.

The coin rotor, clearly visible in the middle of the mech, is the heart of the whole thing. It is equipped with a number of "pockets", each one able to store a coin, which are used both to temporarily hold the coin the user inserted and to give out change after the end of the call; it is equipped with two photointerrupters (circled in blue), one on the input side of the pocket and one on the output side, a small DC motor (circled in red) that is used to turn the rotor one pocket at a time, a coin release solenoid (green) and an absolute encoder (magenta), used to track the rotor's position.

After being released from one of the pockets, the coin goes through another clear polycarbonate channel, with one last solenoid-controlled barrier (yellow); when the barrier is open, the coin goes once again to the change tray (this is used to actually give back change to the used after their call has finished), whereas when the barrier is closed the coin gets sent to the phone's safe. Another photointerrupter checks if the coin actually gets in the safe.

All solenoids on the coin's journey have a microswitch used to check their operation.

First power up

After cleaning it up, I tried to power the phone to check how much of it still works. After scratching my head for a bit and realizing that you do need a charged lead-acid battery to be connected for the thing to power up, I had the first signs of life: a blinking "out of service" LED, the card reader turning its motor for a couple of seconds, and nothing more.

After a lot of more headscratching, I figured out my LCD had a dodgy zebra strip; with some pressure on the display frame, I finally had some output. I put the phone in test mode (switches under the display: left one OFF, right one ON) and was finally greeted with a firmware version string and a test menu.

Good news: it passes all checks apart from the ext RAM test (which is expected seeing that the coin cell on there is dead) and the full mech test (broken microswitch mount for one of the solenoids)....

Read more »First of all, sorry for the delay. Life's been kinda busy and I didn't make any really interesting progress on the project; still, I think I gathered enough material for an update (at least, now you know I'm still alive!).

Anyway, the first major news is that I FINALLY GOT A PHONE! A 4F model from the good old eBay, obviously. Photos will follow when I finish cleaning it and I get the time to drag the damn thing outside to get some nice shots of it. That said, the main reason I got it cheap-ish (we're talking about 100€ instead of the usual 300€+) he thing is in pretty sad shape cosmetically (lots of paint missing, and where it's still attached it's faded) BUT it's complete and it has a card reader with it.

The first problem I had is that it didn't come with a key; no biggie, I thought, the little coin door on the side has a standard puny brass lock, I'll get inside through that. Yeah, it didn't work. I was able to open the coin door itself, but the phone is built like a tank and you can't really access much of anything from there. Long story short, I had to buy a key (there go another 30€ down the drain) to get inside; I'll post the key code here as soon as I decode it, so that anybody interested can cut their own key.

Once inside, however, I was finally able to get a lot of the data I was missing on the internals. Here's the main discoveries I made, in no particular order:

a) Remember the small "mystery board" from log n° 2? Well, turns out it's the card reader interface; The reader itself connects to the upper connector (at least in mine) and the black potted module is a voltage regulator (I already depotted one, hopefully I'll post the schematic soon). This however raises a doubt: remember how I said all the variants of the phone could support a card reader? Well, the original 2F boards don't have the connector for the interface board; I can't say for sure without looking inside an original 2F, but I suspect the card-reader-equipped 2F phone I saw on eBay might have been something

made by the seller.

b) The missing board. The board I didn't have, which is the one in the middle of the mechanical section, is indeed the coin discriminator. It was made by MEI (Mars Electronics) for IPM and its sensor is of the inductive type.

c) Connectors. I figured out the pinouts for most of the connectors:

Again, detailed schematics will follow hopefully soon.

One source of information I initially didn't think to check is the Italian patents database. After all, I knew that some aspects of the phones ARE indeed patented (for example, the magnetic card system), so I realized there might be something helpful in there. Again, here's my discoveries, in random order:

a) Data communication. In my first post, I said that all Rotor phones have the capability to "talk" with the phone company, to report back status information; this was taken from Wikipedia, and I couldn't find any reliable data source (there's some stuff on forum posts, but everybody seems to have a different opinion on the matter). There's no doubt the 4F and the OV models have advanced comms capabilities: the remote card check wouldn't work without it AND we have parts of the OV technical specs that clearly talk about OverVoice HDLC communication; I was always dubious about the 2F model, however, especially after the whole card reader interface discovery and especially...

Read more »As I hinted in the previous log, I managed to score a card reader on an auction site!

Here it is:

This is what would normally fit in the smaller red box on the side of the phone (in the project photo it's on the right). Interestingly, the same reader module (along with the two-wire O.V. board, with a different firmware) is used in the Rotor 3.

The device itself is pretty unusual as far as card readers go. The most obvious difference is the presence of two card slots; the one on the bottom is used only as an exit for the cards and there's a mechanism to prevent you from inserting anything in there.

The differences don't stop here, as you can see from the top view:

Circled in red is the first read head (note that cards are inserted "upside down", with the magnetic strip facing up); a photointerrupter (in green) is used to detect the presence of a card. A stop (under the section highlighted in yellow), controlled by a solenoid, is used to block the access to the rest of the mechanism unless a valid prepaid phone card is inserted. Note that ISO-sized credit cards are ALSO not allowed to go further into the mechanism, since they only need to be read by the first magnetic head once at the beginning of a call and do not need to stay in the reader (in fact, I suspect the entirety of the band is read only when pulling out the card, since the instruction specify to "insert it, then remove it quickly")

If a prepaid card is inserted, the stop moves out of the way and the card is pulled around a rubber coated drum, which can be seen in the next picture (see now why they need to be flexible?):

Around the drum, a series of photointerrupters (again in green) track the position of the card; there are also two more heads used to read and write data on the card; The drum itself is driven via a small motor (the cylindrical part visible at the bottom left of the first picture) and a long belt (which, unusually, is white-colored)

This might seem like a whole lot of unnecessary parts, but you have to keep in mind that the original magnetic phone cards had the credit info written directly on them, with all transaction handled locally, so they needed to a) keep the card in the phone until the end of the call and b) change the card contents before giving it back to the user. They changed pretty soon to a remote verification of the cards, reading the card ID from the magnetic strip and then getting the credit info from a remote database, but the readers stayed the same AND still updated the credit info (probably for backwards compatibility with the readers still using the old firmware).

The first readers built had an interesting "bug": putting a piece of tape on the magnetic strip, increasing the distance from the strip to the write head, was enough to make the write fail, effectively making the card usable for an infinite number of calls. This was fixed pretty soon, and the remote verification made it useless anyway.

The last interesting detail is the presence at the bottom of a mechanism to snip one of the edges of a card (see the picture in the first post: the card is not rectangular) after the first use. This was done to prevent dishonest sellers from giving you a card that had already been used.

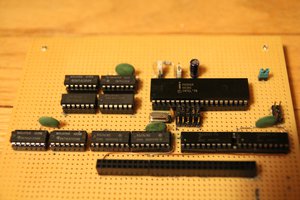

After playing with the mechanisms for a bit, I turned my attention to the board:

As you can see, it's got the same HD6305Y2 MCU, a 27C256 EPROM (already removed in the picture) for the code, and a ST chip I could not identify (which is hooked to the CPU bus); under the copper shield, a ceramic module houses the analog circuitry for the three magnetic heads.

I already dumped the ROM, but without knowing what the mistery "ICWA B22HB9431" chip does I can't fully reverse engineer the code, since it's mapped in memory and thus directly accessed; I still have a lot of code to go through both in this ROM and in the main phone ones, so there will be an update in the future about the code.

I finally found some motivation to start tracing the missing boards (EAGLE files are in the "files" section of the projects).

The CPU board

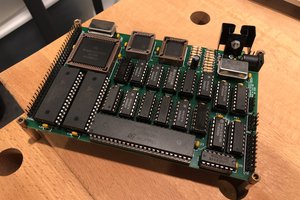

I started with the CPU board:

A few observations, in random order:

The first thing that caught my attention is that the MCU's address and data buses are not exposed to the main board, as I would've thought based on the number of pins on the connectors. How are the external RAM and the config ROM connected to the system then? I was a bit puzzled, but I figured it'd be more clear once I looked at the other boards.

I then started looking into the address decode logic, since I needed to know where the ROM was mapped in the memory space to decompile the code. Looking at the Hitachi manual, here's the basic memory map:

So, the available range for ROM and/or other memory mapped devices is 0x0140-0x3FFF (plus a tiny slice from 0x0020 to 0x003F). Here's where things get bizarre again:

First of all, U3 can disable the ROM through IC1B (or, on boards where the three 74xx series chips are missing and J1 is installed, can control the ROM directly). This is somewhat strange but not totally unexpected, so I moved on. Then I found another problem: if you follow the schematics, you'll see that the chip enable output from the CPU (which is bizarrely active HIGH) is totally ignored by the ROM selection logic and only routed to U3. I checked the Hitachi manual and in the section about connecting an external ROM (PDF page 227, section 3.1.1) it shows a schematic which completely ignores the !CE and !OE pins, so either the internal data bus buffer goes HI-Z automatically when accessing internal RAM/registers (which would make sense, since the diagrams show that there's indeed a buffer), or they put some extra decode logic inside U3 to deselect the ROM when needed.

What really confused me (and I still can't explain) is that the only address where the onboard selection logic (IC1, IC2 and IC3) explicitly deselects the ROM is 0x1FFF; if you check the Hitachi manuals again, you'll see that the reset interrupt vector is stored in ROM at 0x1FFE-0x1FFF (it's a 16 bit pointer to the address of the first instruction to execute, stored big endian), so I really don't understand why you wouldn't want the ROM to be selected while reading that.

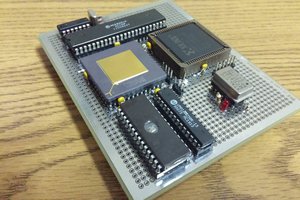

The RAM board

With these discoveries, I moved on the RAM board:

This section here is pretty straightforward. ROM and RAM share the same address and data buses, both of which are exposed to the main board through the only connector present (only address lines A1 to A8 seem to actually be in use, but A9 to A12 are still present on the connector). There's some 40xx series logic that selects the two memory chips (interestingly, they're toggling the !CE line and not the !OE line to select the chips, as they do on the CPU board; this works, but I've usually seen it done the other way round), with the inputs connected to some signals I haven't yet identified (perhaps some kind of bus, since there's a resistor array connected to the four lines?). A small lithium cell is connected to the RAM to retain the data even without power, and an Intersil ICL7665 is used to alert the system when the battery runs low.

This still does not solve the problem of "what is this memory hooked up to?", though, so I started looking at the main board

The main board

I'm still working on the main board (there's a lot more stuff going on there), but I've traced enough of it to find out where the RAM board connects to; if you've looked at the CPU board schematics carefully, you probably already found the answer: it hooks up to the SCL1054-V4 chip, through a second set of address and data buses. This, combined with what I already knew from tracing the other board,...

Read more »Even before attempting to reverse engineer all the code (I still have to trace the CPU board; I've been pretty busy recently and motivation's been kinda low), I knew that things would be a lot harder if I can't find out anything about the mystery suspected-to-be-modems chips.

Since I have a number of them (I have a lot more CPU boards and main boards than line interfaces), I tried decapping the chips, in the remote hope to find some more information one the die (like a non application specific part number).

I used the hot air method to extract the die, which basically consists in heating the plastic packages with a high temperature heat gun until they become soft and then breaking them with pliers. As strange as it sounds, it works (see (13) Chips a la Antoine: an IC chip de-capping recipe without chemicals - YouTube for an example)

Here's the a picture of the decapped chips:

(PLCC package SCL1054-V4 on top, "wide" DIP package Italtel v7308 on the bottom)

Unfortunately, I found out that I do not have a good enough microscope to really analyze these, but I managed to find something interesting inside the SCL1054-V4

An RCA logo and part number! Unfortunately, this also brings up no results. I guess I'll have to resort to analyze the software to understand what these chips do and why.

This is as far as I've gotten for now. I really need to trace the remaining boards and to start working on the software. I do know a bit of 6502 assembly, but I've never really done much assembly programming before, let alone reverse engineering on already written code, so this is probably going to take a while. Also, as said before, I'm missing some info on the internal wiring (mainly about the electromechanical actuators and sensors wiring) so I'm a bit stuck on that front.

As I said in the previous log, I decided to take a break from schematics drawing and to look at the software; I chose to start with the ROM from the Rotor 2 board, since I was reasonably sure that it contained card reader interfacing code and since the board is less integrated and easier to probe if need be. I'm not sure if I can post these here; after all, it's still copyrighted code (but then again, with almost no payphones remaining at all, who would care? )

The first problem I encountered is that the Hitachi HD6305Y2 is not a popular MCU, so there's very little information about it. I managed to find the original Hitachi handbook (http://bitsavers.trailing-edge.com/components/hitachi/_dataBooks/1988_U08_HD6305_Series_Handbook.pdf), but no disassembler or compiler.

This didn't leave much options: if I wanted a disassembler, I had to write one myself. Luckily, the popular reverse engineering tool Ghidra does offer the possibility to add a new architecture. The process is not all that well documented, but luckily I found a Reddit post which explained it pretty well (see https://www.reddit.com/r/ghidra/comments/ba09tk/documentation_on_adding_new_processor/ ). I copied some stuff from the files for the already supported processors and, with the help of the provided SLEIGH documentation (https://ghidra.re/courses/languages/html/sleigh.html) I was able to write my own processor module (you can find it here: https://mega.nz/file/CDQD3SwT#_zkjB--d8NPhUFaqIKVJzupw02vo9lRbekrEkIG6EP4 but there's no guarantee it's error-free).

So, I imported the ROM files into Ghidra, aaand:

Yeah, it's full of errors. I tested the disassembler on a fake ROM i made that contains all the instructions the processor supports in sequence and it recognizes and decodes them correctly, so I strongly suspect this is just due to me not starting the disassembly at the right place in memory (I just dumped the whole ROM from start to end). I need to check the address decode logic on the CPU board to really understand what addresses contain code and what don't.

Just for fun, I imported the Z80 ROM:

This already looks better, AND it looks like they're using one of the MCU serial ports as a debug port, as seen in the highlighted strings.

The next step will probably be tracing the CPU board to get the memory map of the processor, so that I can atleast confirm I'm trying to disassemble code and not random data.

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.

Become a member to follow this project and never miss any updates

Arrow Westervelt

Arrow Westervelt

Mastro Gippo

Mastro Gippo

Bentendo64

Bentendo64