Summary

This project proposes an optical–structural hypothesis about the rotation curves of spiral galaxies. Rather than postulating the existence of invisible mass from the outset, it is suggested that the flatness of the rotation curves may, at least in part, result from the blending of light coming from different layers of the galaxy, from the scattering of central galactic light by interstellar dust and gas, and from spectral averaging along a given line of sight. In this framework, the Doppler signature of the faster inner layers can appear in the spectrum of the outer regions and make the true orbital speed of edge stars appear artificially higher.

1) Introduction to the dark matter problem and the measurement of galactic rotation

One of the main observational arguments for the existence of “dark matter” comes from galaxy rotation curves. These curves are derived from the light of the galaxy, not from a direct tracking of the motion of individual stars.

1.1. How do we measure the rotation of a galaxy from its light?

When a massive object such as a galaxy is rotating, one side of the galactic disk is moving towards us, while the opposite side is moving away from us.

Using the Doppler effect applied to light:

-

the light coming from the part of the galaxy that is approaching us is slightly shifted toward shorter wavelengths → it appears bluer (blueshift);

-

the light coming from the part that is receding from us is slightly shifted toward longer wavelengths → it appears redder (redshift).

In the spectrum of the light emitted by the gas and stars in the galaxy, the well-known spectral lines (for example, hydrogen lines) are therefore shifted slightly toward the blue on the approaching side and slightly toward the red on the receding side.

By measuring the amplitude of this Doppler shift:

-

we determine the direction of rotation of the galaxy,

-

and from the value of the shift, we compute the linear rotation speed of gas and stars at different distances from the galactic centre.

In this way, for each radial distance from the centre of the galaxy, one obtains a rotation speed v(r), and a diagram called the galactic rotation curve can be plotted.

1.2. Theoretical expectation versus observation

In a “normal” gravitational disk where the mass is mainly concentrated in the centre (as in the Solar System, where the dominant mass is the Sun), we expect the orbital speed to decrease with distance from the centre as

v(r) ∝ 1 / sqrt(r).

However, for many spiral galaxies, the rotation curves derived from Doppler observations show that

v(r) ≈ constant.

That is, stars and gas in the outer regions rotate at almost the same speed as in the intermediate regions, while the visible mass (stars and gas in the disk) is not sufficient to generate such high velocities.

To explain this discrepancy, the concept of dark matter was introduced: an invisible mass distributed in the galactic halo, providing the additional gravity required for these large rotation speeds.

Nevertheless, up to now no dark-matter particle has been directly detected, and this has motivated a re-examination of the observation process and of the interpretation of rotation curves with greater care and precision.

2) Nature of optical observation and its limitations

The rotation speed of galaxies is not measured from the actual motion of individual stars; we never directly see the position or displacement of stars in a distant galaxy.

What we observe is only light. And all inferences — speed, disk structure, and even the existence of dark matter — are based on spectral analysis of that light.

Yet, on its way to the telescope, light:

-

travels across extremely large distances,

-

passes through several layers of gas and dust,

-

undergoes multiple events of scattering, absorption, reflection and path change,

-

and finally ends up being mixed, within a single pixel of the telescope detector, with light...

Younes HASSANABADI

Younes HASSANABADI

James Cannan

James Cannan

Anteneh Gashaw

Anteneh Gashaw

bobricius

bobricius

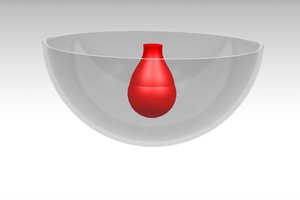

Lisa Taylor

Lisa Taylor

interesting hypothesis..

what about RadioWave especially H band observations? Does it give the same measurement result?