-

I²C/MDIO sharing

01/04/2018 at 17:24 • 1 commentWhy bother?

As I mentioned in the previous log, I'm a little short on pins to hit every function on the ESP32. For all its merits as a microcontroller (and there are a lot), I wish they'd come out with a larger package with more pins (a 64-pin package would allow them to bond all the internally available GPIOs and then some).

Windy uses I²C for one or more GPIO expanders and the temperature sensor, and potentially LCD/OLED output displays. MDIO is used to configure the Ethernet PHY. I had hoped to include SPI for higher-speed peripherals (for example, I²C is fine for character-oriented displays, but it's miserable for pixel-oriented ones, not least because the ESP32's I²C unit isn't DMA-capable). However, again, there's just not a spare pin even for one chip select line.

What I was hoping was that I might be able to share the MDIO and I²C lines either outright or with some sort of multiplexing arrangement using an external multiplexer and a select line. The latter is out of the question; there are no spare pins on the ESP32, and putting the selector pin on an I²C GPIO line would be problematic because once you switched away from I²C, there'd be no way to switch back. So I decided to investigate outright sharing.

The protocols

I²C and MDIO are both pretty simple protocols (MDIO being the simpler of the two). I'll link to the Wikipedia pages for both, which provide decent summaries (and I'm going to steal some images from them below):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I²C

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Management_Data_Input/Output

The question was: would I be able to run both protocols over the same wire without a) unnecessarily loading things, or b) triggering spurious commands on a device I wasn't actually talking to?

Common elements

Both protocols share some common elements: They are both two-wire, multipoint bus protocols which communicate over open-collector lines (this is a bit hand-wavy; in I²C, both the data and clock lines are open-collector because slave devices can stall the clock line to get more time to complete a command, while in MDIO the clock is generally only driven push-pull from the master, but none of that is going to hurt us here). Both protocols clock data in on the rising edge of the clock. After that, the similarities end.

I²C

I²C is designed as a low-speed protocol for connecting lots of devices together reliably. It uses specific Start and Stop sequences to begin and end transmissions; devices start listening to their address after a Start condition and stop listening to everything after a Stop until another Start is issued. In certain circumstances you can issue a "repeated Start" without issuing a Stop condition to e.g. read from a device immediately after you've written the register address.

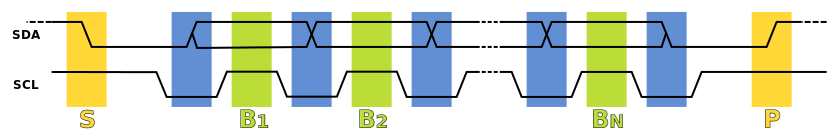

Here's a diagram of a (simplified) I²C transaction:

![I²C transaction I²C transaction]()

Simple I²C transaction The Start condition (denoted by S) consists of a falling SDA (Serial DAta) while SCL (Serial CLock) is high, while the Stop condition (denoted by P) is the opposite (SDA rising while SCL is high). In the data phase, data always transitions when the clock is low; if the data transitions during a high clock, it's an out-of-band framing signal. Data is therefore clocked out on the falling edge of the clock and clocked in on the rising edge.

What this diagram doesn't show is that an I²C transaction starts with a byte consisting of the 7-bit device address and a read/write (R/#W) bit, followed by an acknowledge bit (ACK) from the slave if a device recognized the address. All the following bytes (and ACK bits) involve either the selected device or the host; all other devices stop listening after the address until the next Start condition.

The ACK bit is a logic '0'. This makes some intuitive sense: since I²C is an open-collector bus that is pulled up, if no device responds, the default value will be a logic '1'.

If, at any time, the bus sees a Stop condition, all devices immediately deselect and go idle untl the next Start condition; the Stop condition effectively acts as a reset on the bus. This is true even if you're in the middle of a byte, though the effect on the destination device is indeterminate (well-behaved devices will just ignore the partial byte).

MDIO

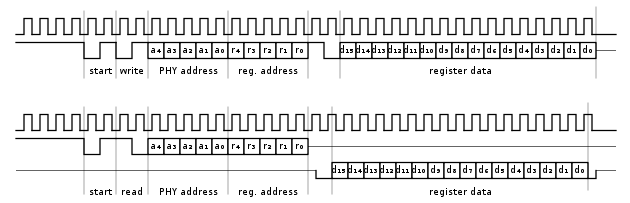

MDIO is a comparatively simpler protocol. There is no out-of-band signaling, and everything is clocked both in and out on the rising edge of the clock. Here's a simple diagram of both a read and a write transaction:

![MDIO Transaction MDIO Transaction]()

A simple set of MDIO transactions What's missing from the diagram is that the transaction expects a preamble of 32 clocks of a logic '1' before the message. IEEE 802.3 Clause 22 (the original MDIO specification) mandates that 32 ones must be observed before the message starts. If you look at the message, this makes sense; the start + opcode section is 4 bits, the PHY address and register address is 10, then there's a 2-bit delay or turnaround time. Then there's 16 bits of data. That adds up to 32 bits worth, so it's easy to synchronize the data with a 32-bit shift register (or a 16-bit one twice).

Thus, to avoid garbage data, a well-behaved implementation won't act on anything if it doesn't see a pile of '1' bits first. MDIO implementations often have a free-running clock (this is sometimes seen in I²C, but is fairly rare), so it's not normally much of a big deal except in back-to-back transactions.

Also worth noting: all transactions must start with an '01' start sequence and a two-bit opcode. In Clause 22, only Write ('01') and Read ('10') opcodes are defined, but the later Clause 45 (from the 802.3ae standard, which defined 10-gigabit Ethernet) adds '00' and '11' opcodes to extend the capabilities of the PHYs and allow both more devices and deeper sub-device addressing. We're probably only going to be talking to Clause 22 PHYs here, but it's worth assuming something might respond to the other opcodes as well.

What does this all mean for sharing?

If both I²C and MDIO devices are going to be on the same lines, they're going to see each other's traffic. The primary concern is that I²C devices hearing MDIO traffic might spuriously recognize their address in there and act on it (performing unwanted operations or corrupting bus data), or vice versa. This is true for both data from the host and responses from the devices.

Case 1: MDIO talking to I²C

This is the simple case. Since all data is clocked out on the rising edge of the clock, if the clock rate is sufficiently slow, the I²C devices will only see Start and Stop conditions and nothing will happen (though it might result in higher-than desired power consumption depending on the receiving I²C state machines, but it's not likely to make much difference).

The MDIO specifications require a minimum 10ns setup and hold on data input to the PHY from the host. There is no maximum value given, but it's reasonable to assume that the PHY output will be output on or shortly after the rising edge of the clock. A naïve implementation might clock out on the falling edge to ensure that the hold time is met, though that might endanger the setup time for the next clock; if that's the case, the I²C device will never see a Start condition and will not be listening for an address.

The same specifications require a maximum 300ns clock-to-output from the PHY. This means that to ensure that the I²C devices only see Start and Stop conditions, we should provide an adequate margin for data to change after the clock before it rises. In general, a 1 MHz clock would suffice, since the low period is 500 ns; this is also likely to be faster than some I²C devices can handle, leading to unexpected results, so some experimentation will be required.

Case 2: I²C talking to MDIO

This one is a little trickier, because there are no out-of-band signals in MDIO that can be used to work around things. Fortunately, we're generally saved by the fact that MDIO requires 32 '1's in a row before it'll accept data.

In general, unless you have a weird I²C implementation that has a free-running clock, you're not going to have a lot of '1's in a row unless you're making a lot of unsuccessful read requests to I²C address 0x7F (an address I don't think I've ever seen in the wild and may in fact be reserved by the spec). If you're just switching back from MDIO mode (where the clock may be free running) to I²C mode (where it's probably not), you can clear out the shift registers by making a dummy transaction to address 0x01 or something (don't do 0x00, because that is occasionally used as a broadcast address, particularly for the SMBus variant).

If you've failed to do that, you're still mostly insulated from potential damage because an MDIO transaction must start with a '01' start sequence. Unfortunately, that covers roughly 1/32 of the potential I²C address space; in particular, the address for the MCP23017 GPIO expander, which this project uses, starts with '0100' (with three user-configurable address bits after that). That would still be an invalid start for a Clause 22 PHY, because the opcode '00' is invalid, but it could cause trouble with a poorly-behaved implementation (and if you plan on doing this sharing with a 10GbE PHY, you could run into problems, but then you probably have enough spare pins that you don't need to share). You would still be further insulated because the rest of the address and subsequent ACK and data are unlikely to match a PHY address, but it's not really worth risking, and there are ways to avoid it, as mentioned.

The only other concern then would be long-running strings of data (e.g. from reading an EEPROM): what happens if we accidentally synchronize the MDIO state machine? Fortunately, that won't happen; the run length of '1's is limited in the data stream because every byte must be followed by an ACK (a '0', if you recall) except for the last one. Therefore, the MDIO state machine will never get synchronized by a normal I²C data stream.

So, we'll always insert a dummy transaction after switching to I²C mode from MDIO mode to avoid spurious MDIO transactions.

Next steps

My PHY development boards are still on the way (one for DP83848, one for LAN8720), so it'll be a bit before I can validate this experimentally, but I'm cautiously optimistic! I'll report back with scope traces once I get a chance to test.

-

Hello, world.

01/03/2018 at 22:17 • 0 commentsSome initial thoughts

Here's a brain dump of the state of things, since this is the first post.

General architecture and motivation

I'm normally not one to let a particular piece of hardware (microcontroller, temperature sensor, etc.) be the driving force behind the project; it's a little backwards from a traditional engineering point of view. However, the idea for this particular project came about because of a confluence of two things:

- I have some fans cooling my entertainment center that I want to control to minimize noise and dust accumulation

- When I first looked at the ESP32, it has very nice 8-way PWMs and pulse counters

Thus, the idea of a fully-connected, 8-way fan controller based on the ESP32 was born. Most of the driving and speed sensing can be done right on the ESP32 itself; the PWMs and the pulse counters take care of most of the standard fan control stuff, and it can handle SD cards natively. An external temperature controller, an analog MUX and a GPIO expander can take care of the rest.

Feature set

Now that we've put the cart well in front of the horse, here's the overall feature set I'm driving towards.

- Control of 8 fans

- Support grouping fans for a targeted speed, optionally synchronizing rotations and/or applying spread spectrum techniques to reduce audible noise

- Support control of non-PWM fans via optional power switches by buffering tachometer pulses (more on that later)

- Support non-tachometer fans via open-loop control

- Measure average fan current and report to user/detect stalls

- 8 temperature sensors

- Apply weighted averages of individual sensors to create specific temperature groups to control fan speeds

- Allow multiple temperature groups for multi-zone fan control

- Support simple home-made temperature probes (2N3904 on two wires)

- Connect via WiFi and Ethernet

- Connect via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE, now also called Bluetooth Smart) for easy smartphone control

- Log data in RAM, optionally providing long-term logging via microSD card

All of these objectives can be accomplished with the ESP32 with a small handful of external support chips (and some discretes, in the case of the power switching/tachometer buffering).

Where I am now

I'm currently chewing through the pinouts of the ESP32 and its pre-made modules (e.g. ESP32-WROOM) to come up with the most efficient assignment matrix. Unfortunately, because of the way the ESP32 modules are pinned out (both the WROOM and the WROVER), prototypes based on the modules will have to be scaled back. The following features are modified:

- Only support 6 fans

- GPIOs 37 and 38 are not pinned out on the modules because they are used solely for the touch sensor cap negative end on the modules

- Only support 3.3v SD cards

- The VDD_SDIO rail is not pinned out on the modules, and the WROOM modules only have 3.3v flash anyway.

Fun challenges for the future

- The only way to fit all these things on the ESP32 is to heavily use multiple functions on some pins

- The SPI flash, the SD card and any external SPI devices must all share the same pins

- This means that internal SPI (source of the program) needs to be shut off while dumping to SD/performing SPI transactions, because there's no nice means of sharing access

- This may have adverse effects on WiFi/Ethernet/BLE stacks and will involve quite a bit of work

- The I2C and MDIO buses need to share pins

- This is somewhat easier, but requires some rework of the MDIO accesses to switch back and forth

- On the other hand, it just might be possible to safely share the lines without switching, but I need to double-check that

- Ultimately, the external SPI bus (currently envisioned for peripherals like OLED display) may have to go because there's just one pin too few

- The SPI flash, the SD card and any external SPI devices must all share the same pins

That's the brain dump for now. More to come once I've actually done some more research!

Windy

A connected, multi-way fan controller with synchronization and temperature logging

Dave

Dave