-

Friday, October 7th - "Wait, you're making WHAT?!"

10/11/2016 at 05:22 • 0 comments![]()

Innovating in such a controversial, traditionally “shameful” space has set us up as fodder for all sorts of strong opinions. From high praise and anticipation, to laughter and even disgust, we feel we’ve seen it all. And for such a small company so recently founded, the latter can be, and in some cases has been, enough of a deterrent to survival that quitting seems like the best option for all parties involved. In our case, however, the disbelief and objections we’ve received have only served to fuel our fire to continue as long as we are able, because this resistance only goes to show that the innovation in question is truly revolutionary.

When we first started out as a class project, we called ourselves “Team Taboo,” and that theme has carried through till now. This week on a television appearance in Spain I highlighted, albeit in my broken Spanish, that reducing the stigma and taboo around menstruation was indeed one of our driving goals.

Because while most men I have talked to about my company become immediately visibly uncomfortable, more often than not trying to break the thick ice with a disclaimer that they “can’t really relate to this personally,” some women have also been quite critical. Indeed Dana Wollman, a female journalist from Engadget, in her piece about us entitled “Who needs a smart tampon when you have common sense?” stresses that over the years her and others’ cycles have started to “run like clockwork...Even without the help of an app, I know when my period will start, which days will be the heaviest be and how long on each day I can get away with leaving a tampon in.” As such, our product is absolutely not for everyone. However many menstruators we’ve talked to, no matter how post-pubescent, are still thrown curveballs on the monthly in terms of both density and timing of their flow. Others lose track of whether or not they’ve put in a tampon and when. Still others are chronically heavy bleeders, in search for a way to quantitatively measure the heaviness of their flow to monitor risks of anemia, Abnormal Uterine Bleeding, and more. In my time in this space thus far, I have yet to discern a correlation between an individual’s common sense and the presence of the above conditions, and I don’t think I will anytime soon.

Really though, everyone is entitled to their opinion, and it’s a given in the startup community that not only are haters a sign of success, but lack thereof might actually be a bad sign. So while the road has not been easy, we’ve realized that innovation in this long-overlooked space is more than necessary.

-

Friday, September 30th - Machine Learning and Steps Forward

10/11/2016 at 03:04 • 0 commentsThe latest step on our quest for menstrual innovation has taken us into the exciting world of machine learning. Yes, it may be a big buzzword nowadays, but there’s a reason it’s getting so much attention: ML is an incredibly powerful tool for the right applications.

Dusting off my programming skills, I dove into some tutorials I found online, worked through the many resulting bugs (praise be to stackoverflow), and ended up with a pretty nice, if basic, machine learning script which combed through our data, extracted salient features, and ran them through an ML algorithm.

Now, here’s where it’s going to get a little vague; my apologies in advance. Because we’re still early stage, I can’t talk too much about the specifics of the data we’re gathering, but I can talk about the code itself, and the success we’ve had. So let’s get to that!

I started out using a neural net classifier, implemented through pybrain, as that was the extent of my knowledge of machine learning when I began this a few weeks ago. I achieved moderate success for my rookie status: usually scoring in the range of 75-80% accuracy. It did well enough to show that there was potential, but I wanted to see if it could do even better. So I switched gears to an SVM classifier, which fared even better, achieving an accuracy of 87.5%!

Heartened by this success, and on the advice of a friend who knows a lot more about machine learning than I do, I decided this was adequate proof of concept, and moved onto the real challenge: predicting percent saturation. So far I’ve had mixed results. The big issue is that our data, which play nicely with classification, are causing us more trouble with gradient detection. For an illustration of this, look at the plot below: a simple regression on a test set of our data (here, using only one feature to predict percentage).

I’m confident that this is not an intractable problem, but it’s clear that this data isn’t going to play well with our algorithms. To fix this, I’ll have to step up my feature extraction game. Until now, I’ve been using some of the most obvious, surface-level features of the data for my analysis, and have not utilized any of sklearn’s various feature extraction functions. Once I get started on that, I’m very excited to see what sort of accuracy we can get.

-

Friday, September 9th, 2016 - Innovation and Failure

10/11/2016 at 03:03 • 0 commentsElon Musk once said “if things are not failing, you are not innovating enough.” Today, I want to write about some of our failures.

When we decided to focus our efforts on pushing forward to a V2 of our current product, a wireless device that could work with any off-the-shelf tampon, we had a lot of options for what technology to pursue. We started with the idea of a clip-on device that would attach to a tampon string, reading out data that could be used to predict the saturation of the tampon itself. For a more in-depth discussion of how we collected this data, see our earlier entry on construction of our jigs.

The first thing I tried to read out was capacitance; given the salty nature of menstrual fluid, I figured it would be easy to register its presence with a capacitance sensor. And I was right!

The data showed a clear relationship between tampon saturation and capacitance, as expected. The problem came when I introduced interference. In order to get this data from the tampon string, I had to make our capacitance sensor pretty sensitive. In fact, it was sensitive enough that simply placing a hand within 6 inches of the tampon caused capacitance readings to spike into the thousands, completely drowning out the good, readable data that I was getting. Clearly, the ambient capacitance of the human body ruled out that sensing method.

Next, I tried conductance. This would solve the ambient noise problem of capacitance by restricting our sensing to only the length of the tampon string. This way, the human body could not cause interference simply by being nearby. And, since menstrual fluid is highly ionic, I knew that higher saturation would result in a noticeable increase in conductance. Well, I was right about that much. However, restricting the sensing window to just the length of the string introduced another problem: cotton is bad at wicking moisture.

By the time our sensor registered any change in conductance, the tampon was already completely soaked. This is good news for tampon users, as wicking moisture down into the string before the tampon is full is bad, but it was bad news for us, as it made the string a useless source of information for conductance data. I was going to have to take another approach.

My last attempt was to measure the temperature fluctuations of the tampon string over time, as the tampon saturated in a constant-temperature environment. I hoped that heat would wick better than moisture, and the tampon string would undergo some distinct temperature change as the tampon itself filled with warm fluid.

Unfortunately, I was unable to find any such correlation. Even after repeated trials, the data was not consistent enough to suggest any identifiable pattern.

So our initial idea of using the tampon string didn’t go over so well. But we did learn a few important lessons. First: cotton is a bad conductor. Second: failure is an important part of moving forward. These approaches may not have borne fruit, but we couldn’t have gotten to where we are now without trying them.

-

Thursday, September 1st, 2016 - Making Functional Jigs on a Budget

10/11/2016 at 02:57 • 0 commentsEvery engineer worth their salt knows that one of the most important parts of a product is the test jig; a good jig allows you to collect accurate, consistent data on the performance of your product. This lets you make the tweaks that improve performance, and take your invention from something that can work, to something that can’t not work.

Since testing my.Flow requires not just a participant willing to make public something that’s normally intensely private, but the proper alignment of their time of the month with our time, it’s difficult to field-test. And even when we do test, it’s impossible to control conditions like flow rate, consistency, and content, making our data tough to analyze against each other. But, precisely because its application is so sensitive, testing is incredibly important! We needed a new jig for an upcoming set of tests, but we couldn’t break the bank getting it.

We looked at a lot of different options for test jigs, from professional-grade synthetic biological system vendors (shout out to Syndaver!) to educational tools for medical institutions, to the Fleshlight, a sex toy in the form of a synthetic vagina. But we couldn’t find anything that was both affordable, and accurate within our needs. So, we built our own.

It was actually a lot simpler, and cheaper, than we thought - the important thing was to realize that every test needs a jig with certain properties of the human body, but no test needs a jig with every property. With this in mind, I built two jigs, customizing each for its own set of tests. I ended up with results that were cheap, fast, and satisfactory, three things that startups love.

I used the first jig (pictured above) to test conductance and capacitance. It consisted of a cylinder of sandpaper to hold the tampon in position, a cutout paper cup to catch excess fluid, and a slat of wood to keep the whole thing stable. And that’s pretty much it. But that’s all we needed for a first round of tests. If these methods had shown promise, I would have added to the jig to account for other complications of the human body (electrical interference, heat, etc.), increasing cost and complexity. But, since these tests didn’t bear fruit, we ended up saving ourselves a lot of time and money.

For the thermal testing jig, I used a standard 2-liter soda bottle filled with water to maintain a constant-temperature environment, and condoms to insulate the tampons from the water (because apparently everyhing at our company comes back to reproductive health products). I debated including an aquarium heater to help maintain the temperature at 98.6, but decided against it as our tests went quickly enough that there was no significant temperature change. The condom was sealed with RTV silicone after insertion of the IV needle to prevent the water in the tank from leaking in, and we even threw in a heating pad, surrounding the tampon string, to approximate thermal interference from a human body.

The jigs that we built for these tests, which could have cost us thousands of dollars, came out to around $100 all told.

-

Monday August 29, 2016 - On Interning at my.Flow

10/11/2016 at 00:07 • 0 commentsWorking at my.Flow this summer gave me an insight into the dynamic startup environment and helped develop my technical and communication skills. I had quit my position in diagnostic device manufacturing to complete a Masters of Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley to translate my background and interests to a career in medical device development. I met Jacob and Amanda over Skype as they were finishing up HAX, a hardware accelerator in China. I was enthusiastic about the groundbreaking product and their public reception but most importantly I was inspired by their mission to change the dialogue around menstruation.

Within the first hour of meeting Amanda and Jacob, I was giving my feedback on my.Flow’s current product iteration and contributing to the company’s summer plan. I found this efficiency refreshing after 18 months of stifling adherence to protocols and rigid schedules.

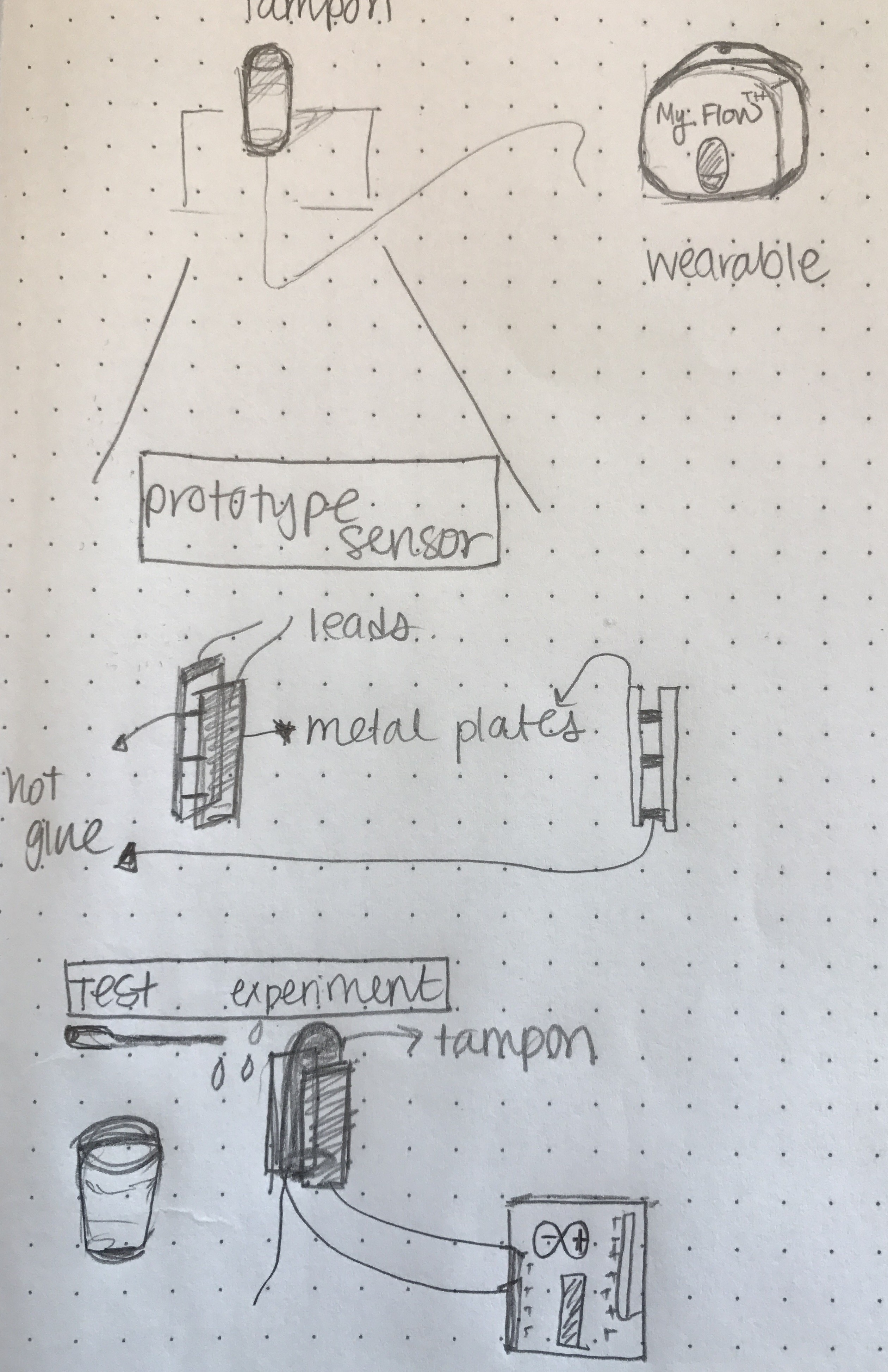

After their initial reception my.Flow was looking to iterate on their sensing technology. I investigated various wired and wireless saturation sensing mechanisms. In line with my. Flow’s lean startup methodology, I created a low fidelity prototype to test my design.

![]()

I didn’t just contribute to the design of the product, I also worked on various other projects as roles in a startup are fluid. I learned how to pitch to different audiences and conduct market research. I learned a lot observing Amanda pitch at the events, tactfully sidestep questions that could reveal proprietary information and remain composed even when her pitch was followed by snickers in male dominated environments.

In an atmosphere where everyone is vying for a finite amount of capital, competition is inevitable. But at many events, I was pleasantly surprised by the support the startup community provided. We were often given useful feedback, suggested potential user groups and provided fruitful leads. Working at my.flow I not only learned about saturation sensors but I also got a glimpse into the inner workings of a young start up. I look forward to seeing my.Flow succeed and bring peace of mind, period.

-

Wednesday, July 27th, 2016 - Today I Built Something Great

09/10/2016 at 05:20 • 0 commentsFollowing up on our log “Today I Built a Vagina,” here is the progress we have made to our jig.

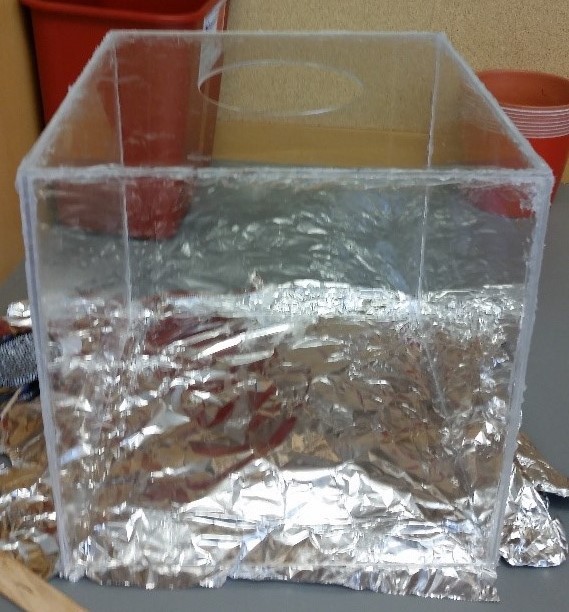

We created an enclosure for our experimental jig. This enclosure was cut from a 0.98” x 30” x 36” clear acrylic sheet. Using a laser cutter, we cut down the sheet into 6 panels measuring 10 x 10” each. One of the panels was cut to have an additional 3 in diameter hole in the center. A marine sealant was used to join the acrylic squares together, and the apparatus was left to dry for 24 hours. We used marine sealant to ensure that the enclosure would be leak-proof.

![]()

The PDMS structure made on June 23rd was recreated to add texture and slight angling to the inside of the “vaginal cavity” to better reflect anatomical measurements. A PDMS base (150mm diameter x 4mm thickness) was then added to the bottom of the vaginal structure to provide standing support. The “vaginal cavity” was joined with the enclosure (bottom panel with 3” diameter whole) using marine sealant.

![]()

A thermometer and aquatic heater were also added to the inside of the enclosure. Using this set up, we plan on filling the enclosure with water and heating it up to body temperature, allowing us to gauge heat sensitivity and its effects on our product.

![]()

We are using an IV bag, IV flow regulator, and various needle gauges to simulate the menstrual flow into the “vaginal cavity”. The needle will be inserted into the top of the “vaginal cavity,” and the gravity/flow regulator will regulate “flow” from the IV bag. We are currently using saline as our “flow” material, but are looking into more accurate approximations of menstrual fluid to test with as well.

-

Thursday, June 23rd, 2016 - Today I Built a Vagina

07/10/2016 at 21:15 • 0 commentsIn order to test how well our my.Flow device is calculating the saturation of your tampon we needed to create an artificial vagina. With all the sex toys out in the world you would think finding an artificial vagina would be easy, right? Well the my.Flow team soon found out that it wasn’t so easy. The vagina is a beautifully complicated structure of a menstruator’s body. It has physical, conductive, and thermal properties that not many people often think about.

Our my.Flow team has been continuously designing an artificial vagina that will mimic the natural and biological properties of the human vagina.

We first started off with researching the dimensions, angle, and size of the vagina. The vagina in simple terms is a 30 degree angled tube that is approximately 9.5 cm in length and about 2.0 to 3.0 cm in diameter. By using the dimensions above, a mold of a vagina was created using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS).

![]()

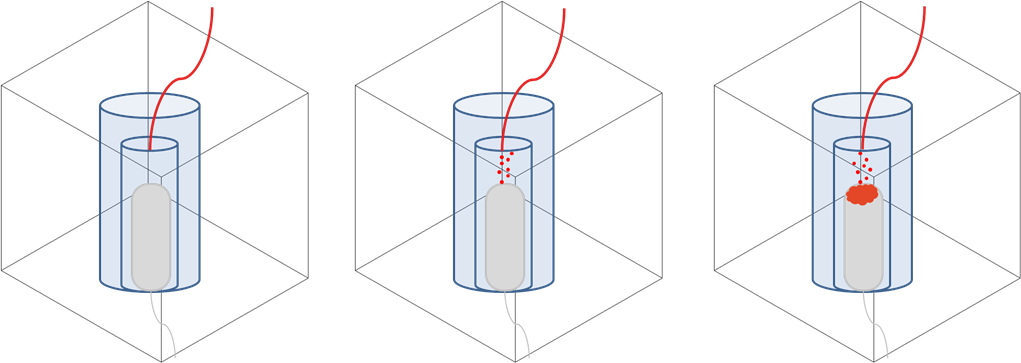

Future steps in our vaginal test jig will be adding flow regulating tubes to mimic the flow of a period and placing the jig in a body temperature regulated environment. We originally wanted to emulate the multidirectional flow of menstrual fluid exiting the uterus through the vaginal canal by having two tubes in the jig (Version 1). After further consideration we decided a centrally located tube flowing from the top would more accurately approximate the menstrual flow (Version 2).

Version 1

Version 2

![]()

-

Sunday, May 8th, 2016 - Pretty Tampons Made Quick (or, Moonlighting as a MechE)

07/10/2016 at 21:04 • 0 commentsWhen you’re demoing a tampon monitor, it really helps to have tampons. And when tampons aren’t reusable (which is always), it helps to have a lot. So, in the aftermath of the insanity leading up to our May 6th China Demo Day, Amanda and I found ourselves with no shortage of work on our hands. And, with Amanda leaving for our press tour on May 9th, we found ourselves with not much time to do it in.

As any computer scientist worth their salt knows, if you have to do anything more than once, it’s best to just write a program to handle it. By the same token, we elected to skip the arduous process of hand-making the many tampons that we needed in favor of building a jig that would do it quickly.

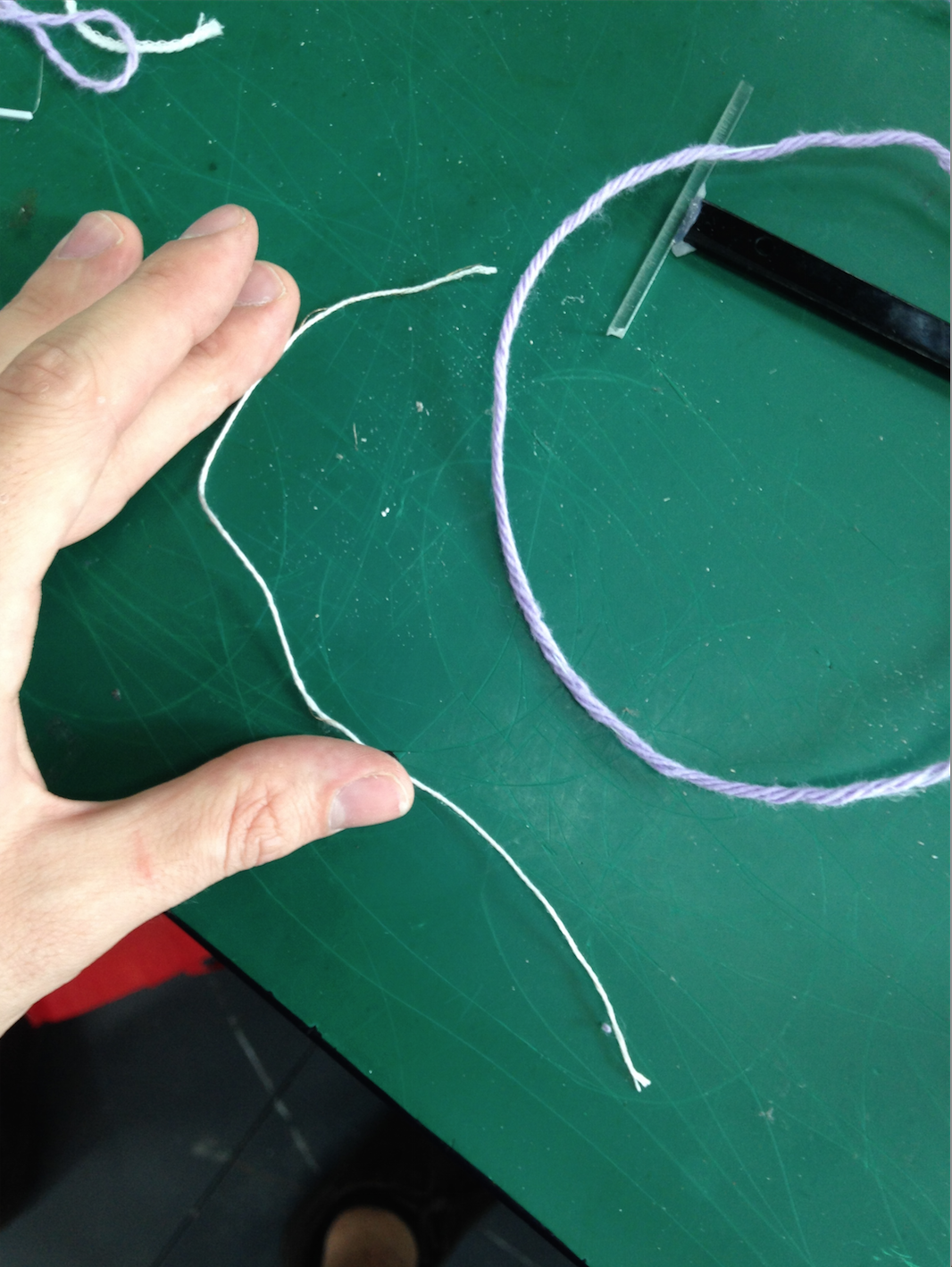

Using wire as we were, instead of conductive thread, there were three parts to the process of creating a tampon. First: strip the wires and trim off any excess cores, leaving only enough to thread the tampon as we desired. Simple enough. Second: sew these wires through the tampons that we had bought. Easy. Third: wrap the wire cords in string so that the tampons wouldn’t look like clunky, electronic monstrosities. This last step had absolutely nothing to do with the functionality of our demo tampons, but was an aesthetic imperative; even those who don’t normally use feminine hygiene products would be put off by seeing one with a bare electric cord trailing out. These first two tasks were easy enough to do by hand. The third, while simple, took far too much time for our needs; thoroughly wrapping one tampon cord could take anywhere between ten or fifteen minutes, not to mention a hefty chunk of both Amanda and my sanity. In order to solve this problem, I got to dip my toe back into mechanical engineering, and put together a neat little jig.

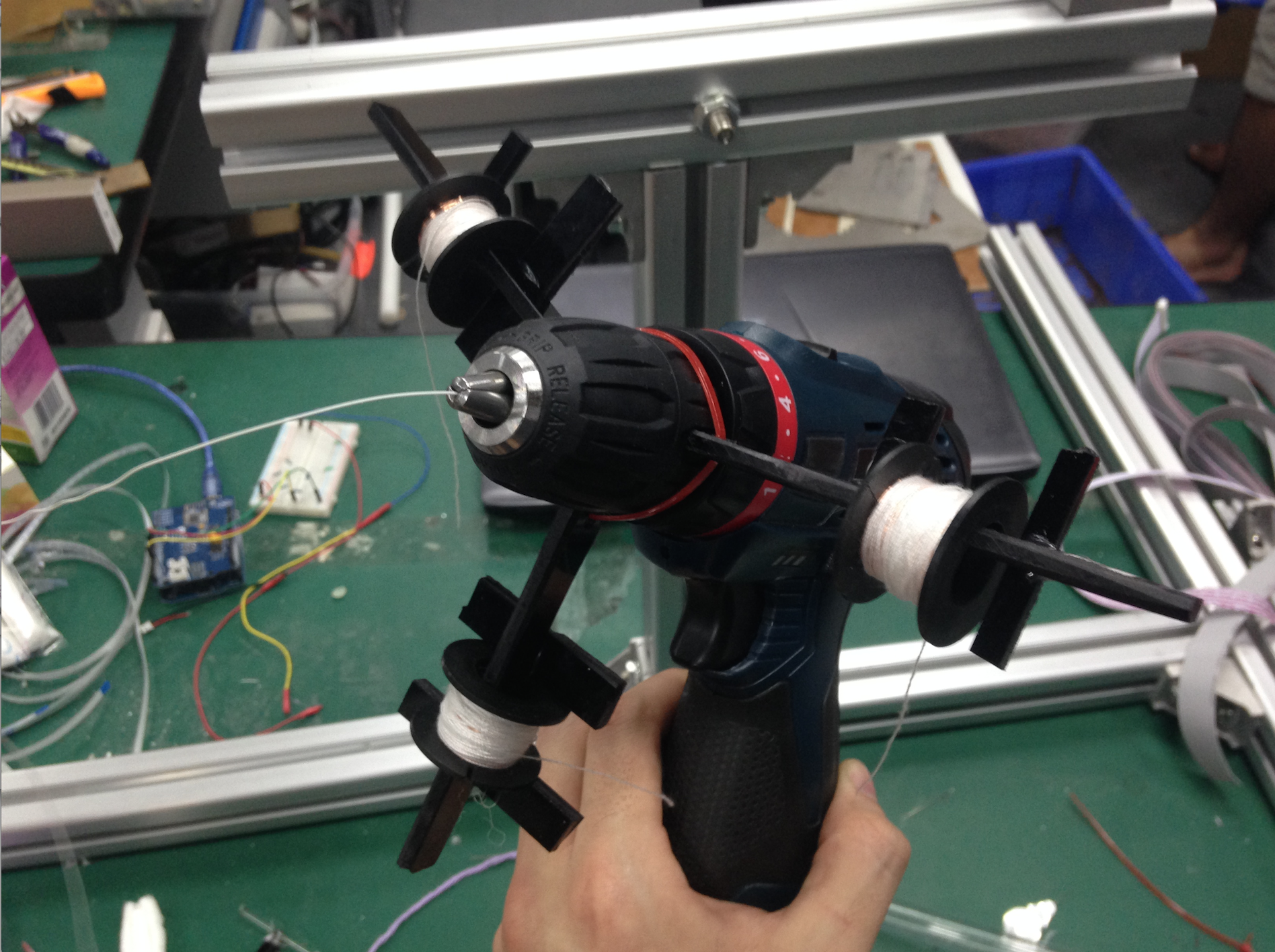

![]()

After brainstorming for an hour, talking the matter over with some friends at Kniterate (thanks, guys!), and watching more than a few youtube videos on modern and medieval methods for spinning rope, we had our first prototype: a simple metal frame on which we could clamp down the section of wire we would be wrapping. Before affixing this wire, we threaded it through a hole in the center of a small acrylic I-beam. Fixing the ends of two strings to the wire’s end, we wrapped the other ends around the different sides of the acrylic beam. Thus, by spinning the beam and moving it across the wire, all while applying trace amounts of glue, we could encircle our wire in white thread.

The flaws with this design quickly became apparent: the thread lay too slackly across the wire, and was spaced too widely. Due to the hand-operated and imprecise nature of the mechanism, the spacing was also irregular enough as to be unattractive. For the next iteration, we needed more precision, speed, and force. Not to mention at least one more line of thread. Thankfully, it’s pretty easy to find something that rotates quickly and precisely in your average machine shop.

We decided to cut the I-beam into halves, and affix each to the outside of a cordless drill’s chuck, running the wire into the chuck itself. This way we could, by pulling gently backward on the drill, maintain the same tension in the string, but wrap at a much greater rate. We also added a third line for good measure. After one trial run, we ran into another problem: now that the string applicator was rotating quickly, it tangled up the strings in each other and in the drill shaft. We needed a way to make the thread come off smoothly and cleanly.

So we added one final change to our design: keeping the thread on the spools it originally came in, and adding a second bar to our I-beams to keep the spools in place. Once they were all placed on it ran very well: laying down string tightly, quickly, and cleanly.

![]()

So we managed to crank out quite a few tampons in time for Amanda’s flight back to the USA. After several months of hardcore electrical engineering and managerial work, it felt good to get my hands dirty with some mechanical engineering. And the fact that I got to make what looks like a ray gun from an old B scifi movie really doesn’t hurt.

-

Saturday, April 16, 2016 - Looking for Housing

07/10/2016 at 20:53 • 0 commentsAs a product catering to a need that’s highly personal, it’s important that our design follow our ideas and exude feelings of efficacy, modernity, and comfort, all while providing the necessary strength and ergonomic finesse to hold the guts together while still being easy to wear. Basically, we realized early on that our ID was going to be very important.

Our first take on the design was an attempt to turn a bug into a feature. We knew that our current conception of the device would have to be worn on the waist, which meant some sort of clip would be required. As the idea of having a spring-powered clip seemed a little traditional and blah to us, we decided to try out something that would incorporate the wrapping-over of the clip into the design of the housing itself, making use of the “clip” space to hold our components, and thus minimizing our device’s profile. The purple spot is the power button![]()

![]()

However, this design ended up giving the impression of being a little too clunky, and most women we showed it to didn’t like how obvious the external portion was. We decided to change gears back to our original idea of making the housing one coherent whole, and attaching a clip to it, in order to make it a bit more discrete. Our second attempt was based on the idea that this device should be able to blend in with car keys a wallet, a phone, and whatever else our customers commonly carry around with them. As we wanted to make it as familiar as possible (again, important for creating a sense of comfort with the product), we chose to emulate a key fob.

![]()

![]()

This design was a lot more discrete than the first, but everyone we asked still thought it was too bulky. For our next design, we prioritized a slim profile first, and discretion second; at this point we wanted to have something that could comfortably worn inside the pants, and would also allow our users to have it be as visible, or invisible, as they wanted. We slimmed down the bulb of our second attempt and ended up with the disk below.

![]()

This got much better feedback than the last two! Although we liked the idea, we decided to tweak it by making it more of an oval than a circle, as that fits more ergonomically along the pelvis where we envisioned it being worn. And that’s how we ended up with the design we presented at our demo in May.

-

Saturday, March 26, 2016 - We're so 'Appy

07/10/2016 at 20:26 • 0 commentsAh, phones. Can’t live with...out ‘em. Virtually all emerging hardware devices feature a companion app, and my.Flow is no exception. As do most developers, we want our app to be realistically useful, visually appealing, and perhaps most importantly, incredibly intuitive.

Our smartphone UI alerts our users as to the saturation level of their tampons by communicating with our Bluetooth-enabled wearable. Once we decided on this primary function, we set out to determine what, if other, options, displays, and information our users might find helpful. We opted to provide graphical representation of flow over time, both on monthly and daily levels, predictions of next period and ovulation cycle milestones, options to adjust notification frequency and content, and information on our product, menstruation, and vaginal health in general.

We had originally started during our class project with an Android app, but based on market research of a subset of our potential users, we transitioned to iOS, with a brief stopover at Evothings (highly recommended for tester apps!) in the middle there.

Our current iPhone app - designed by Mark Ruiz - features a homepage that displays realtime saturation level notification, both visually on a circle, and exactly via percentage. The next page displays flow trends, and the following pages allow the user to learn more, and modify the content of their notifications. Modification of their timing is done on the first page, as displayed in the second pane below; the user simply holds their finger over the gray dots that appear, which grants them the ability to drag the dot, which becomes green, to anywhere on the circle - when saturation reaches that level, they will receive a notification.

We've gotten rave reviews on this latest version, and are continuing to iterate. We are also excited to use our app to collect data and create a macro-database of menstruation, the likes of which have never been seen, with applications in the healthcare, insurance academic, clinical, and research sects. The vast majority of women we talked to – 82% – are comfortable with having their data aggregated to our server and shared with the health community at large in order to learn more about the period as a biological phenomenon, and to improve products like ours. This brings a highly exciting and applicable B2B application to our tech.

my.Flow

my.Flow is the world's first tampon monitor, tracking saturation level with the goal of eliminating period anxiety, leakage, and infection.

Amanda Brief

Amanda Brief