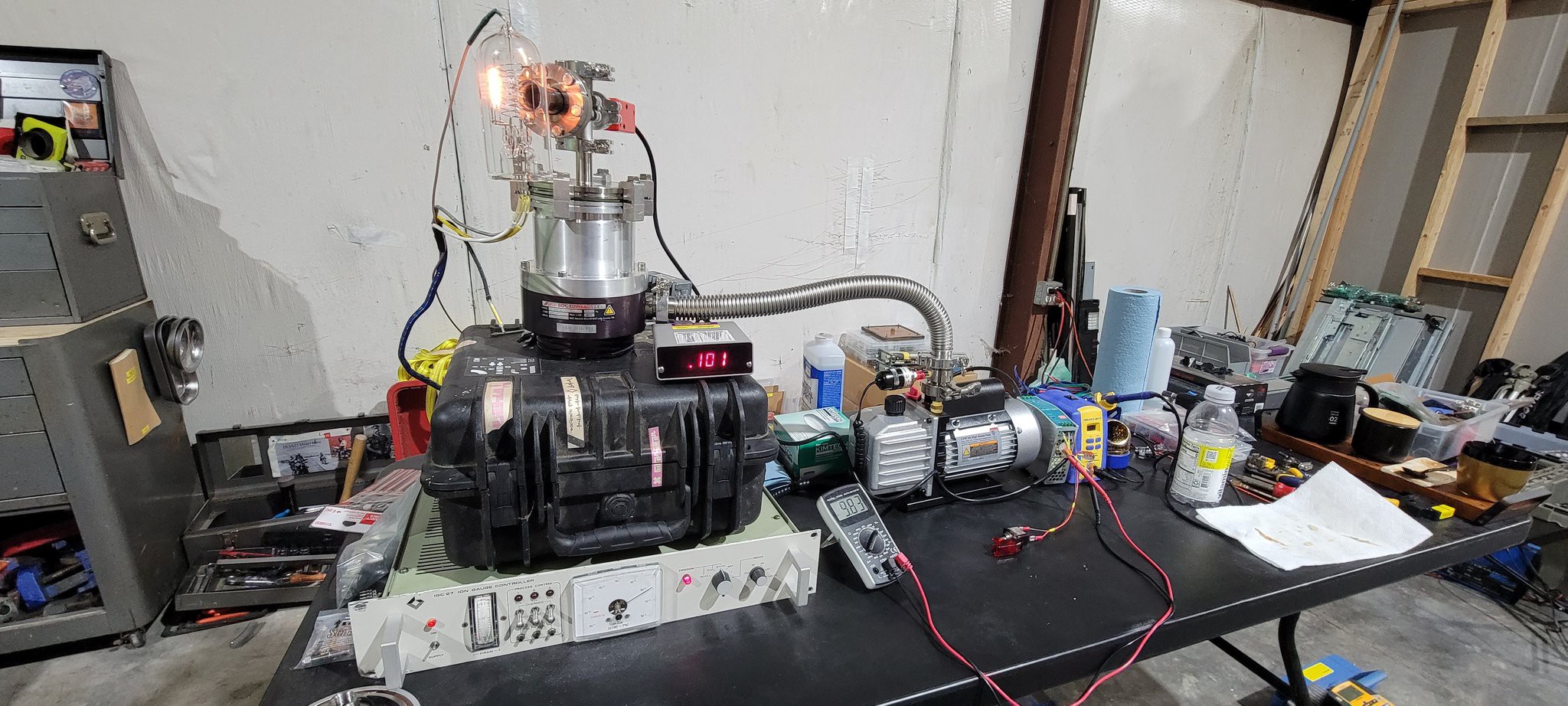

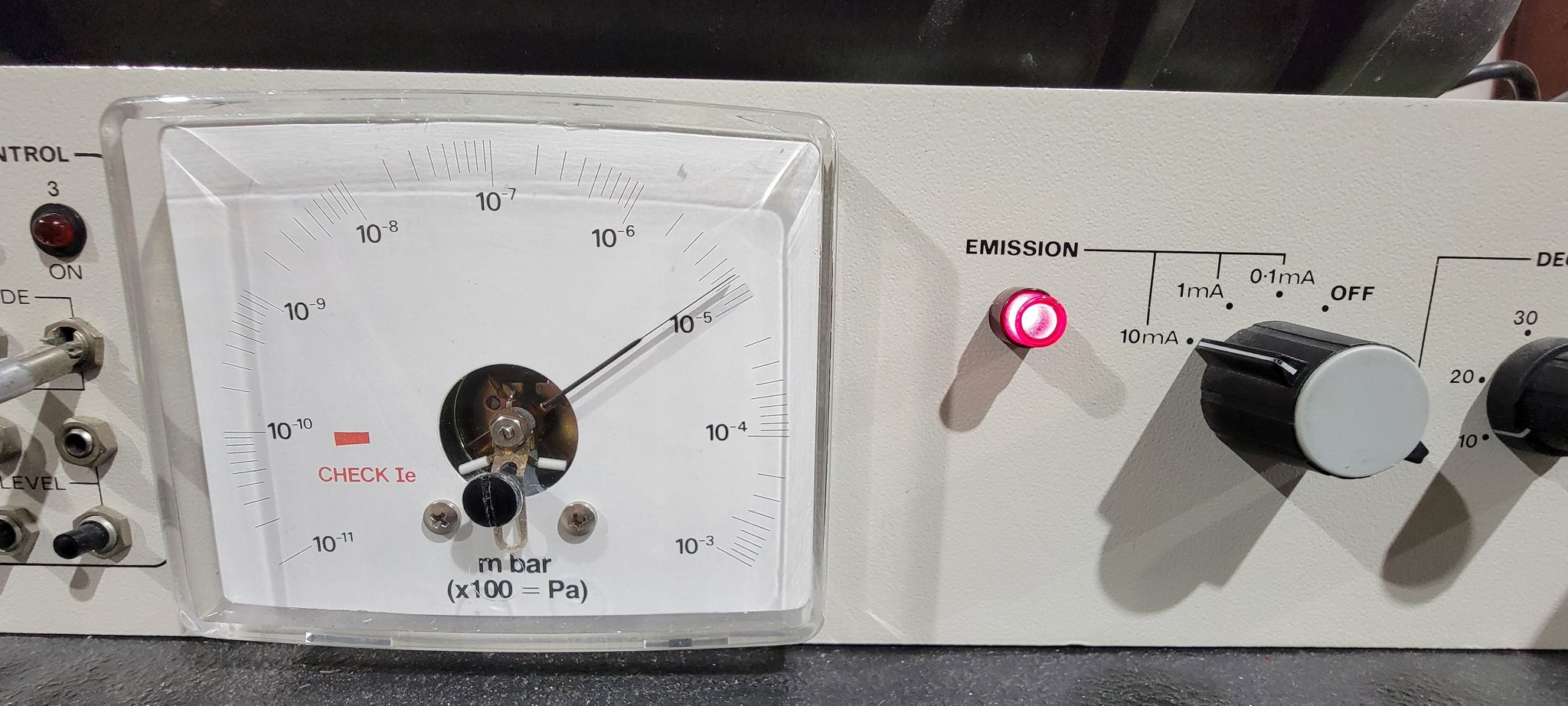

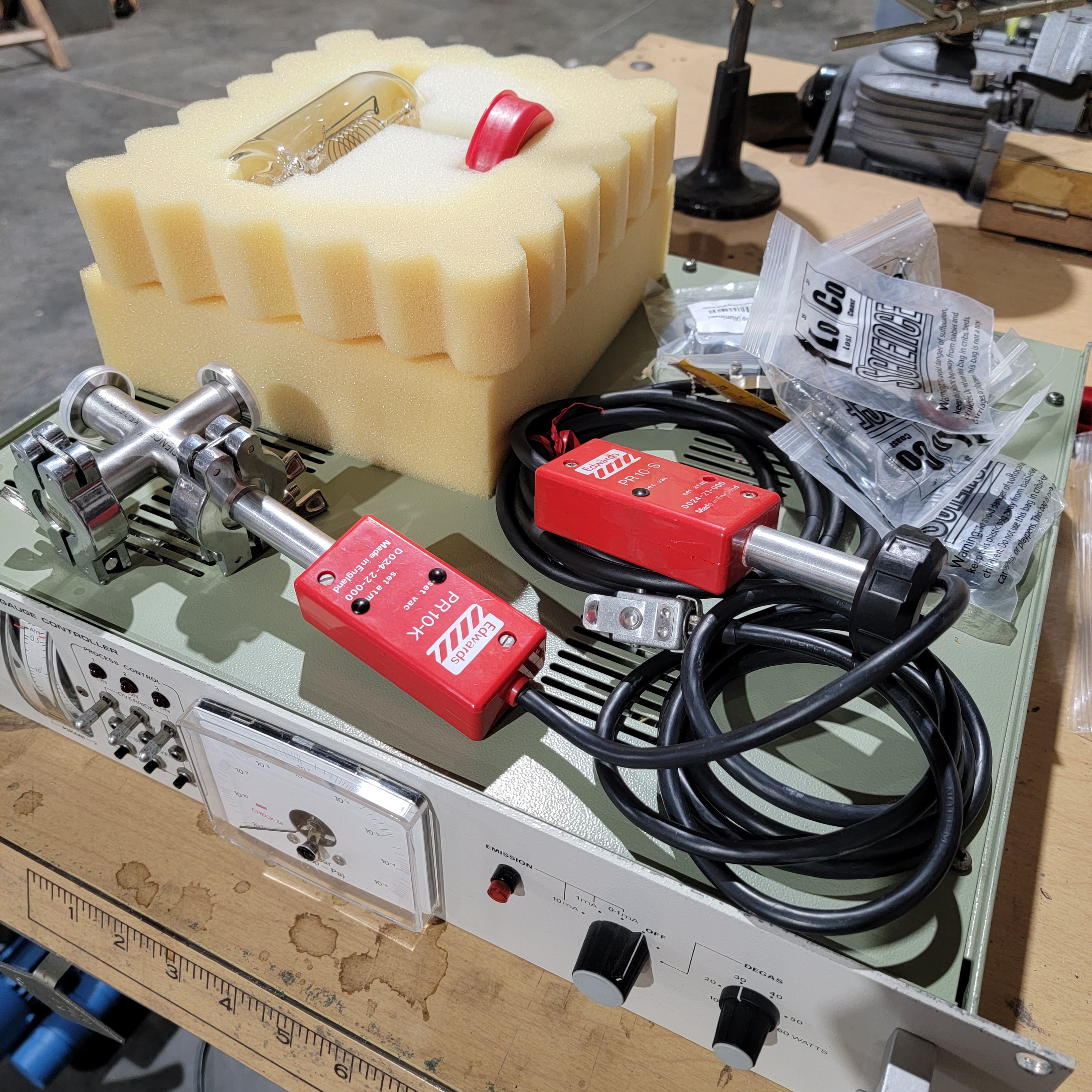

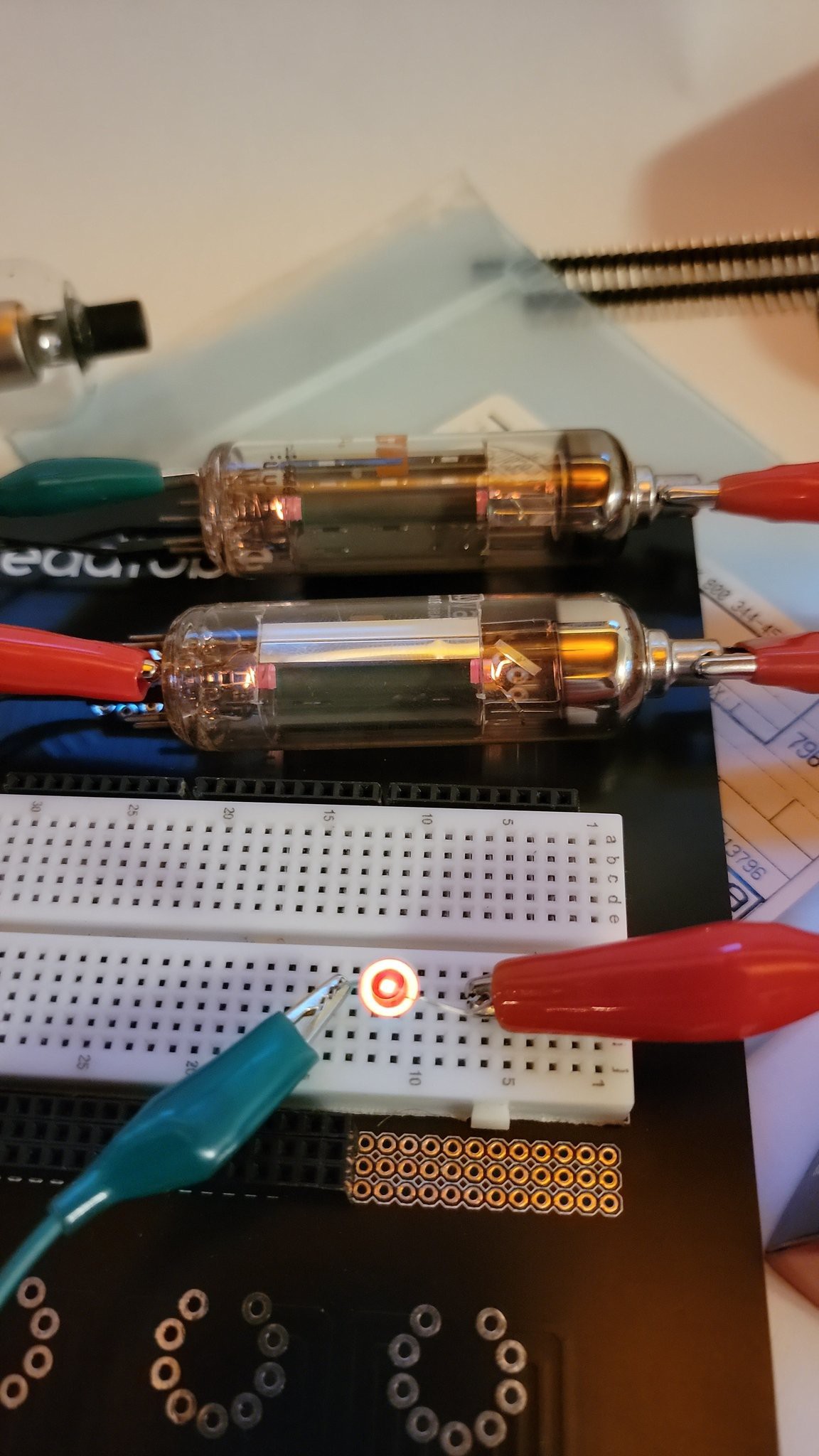

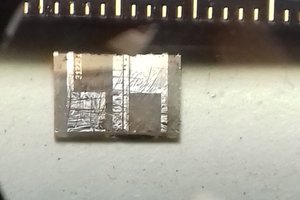

As I'm gearing up to make more traditional styles of vacuum tubes (diodes, triodes, VFDs) I'm going to have all of the equipment I need to build, evacuate, and test my own Solar Thermionic Conversion tubes. I know that they'll never be as efficient as silicon-based photovoltaics, but they have their own advantages. The fact that you can build them with a torch, a vacuum pump, and a spot welder (more or less) means that these are extremely accessible devices. There's no need to get your hands on doped silicon wafers or exotic dyes or spin-coating equipment (although, there are some great demonstrations of homemade silicon photovoltaic cells out there!) So it's possible for remote communities to manufacture these devices themselves.

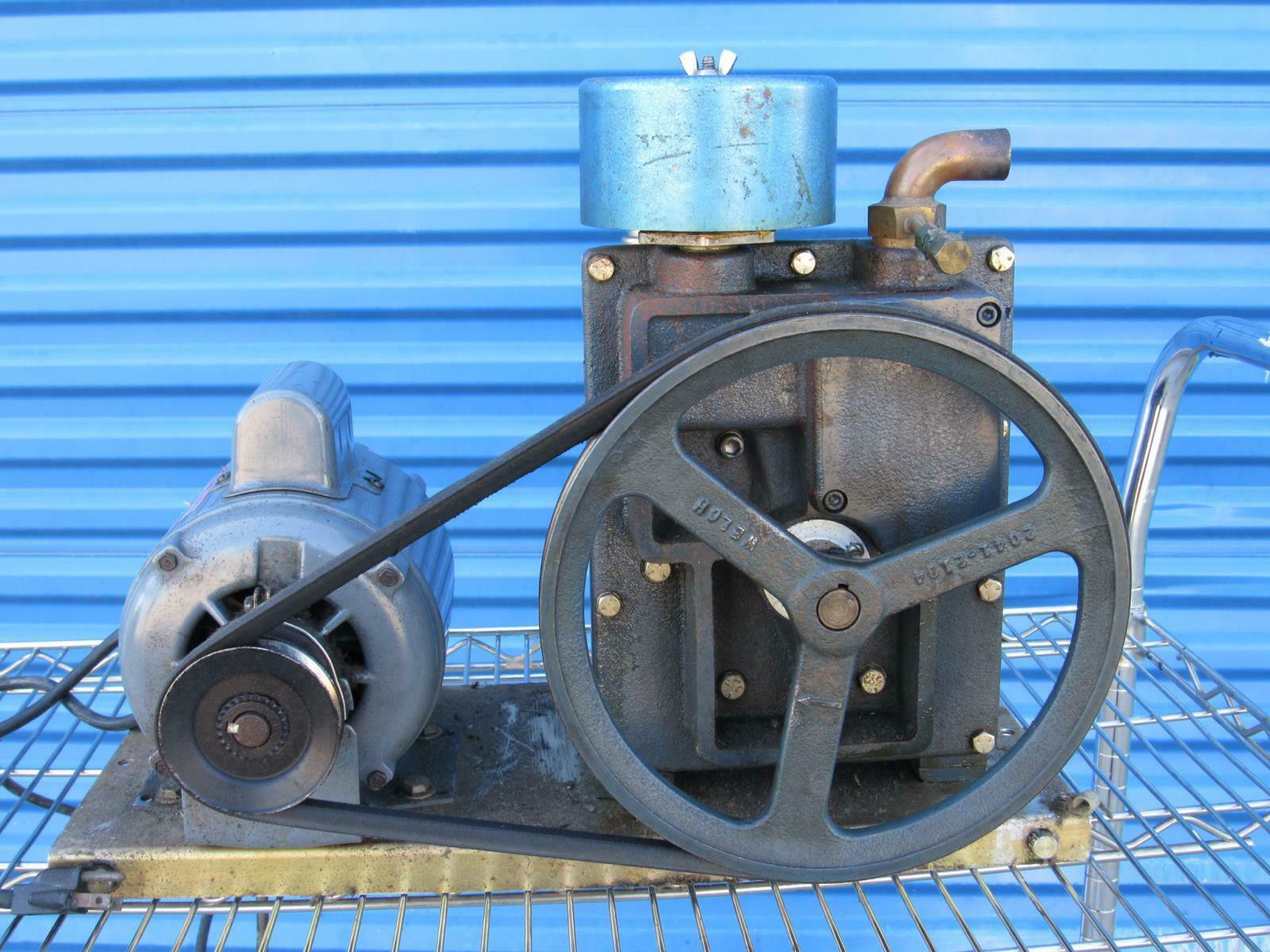

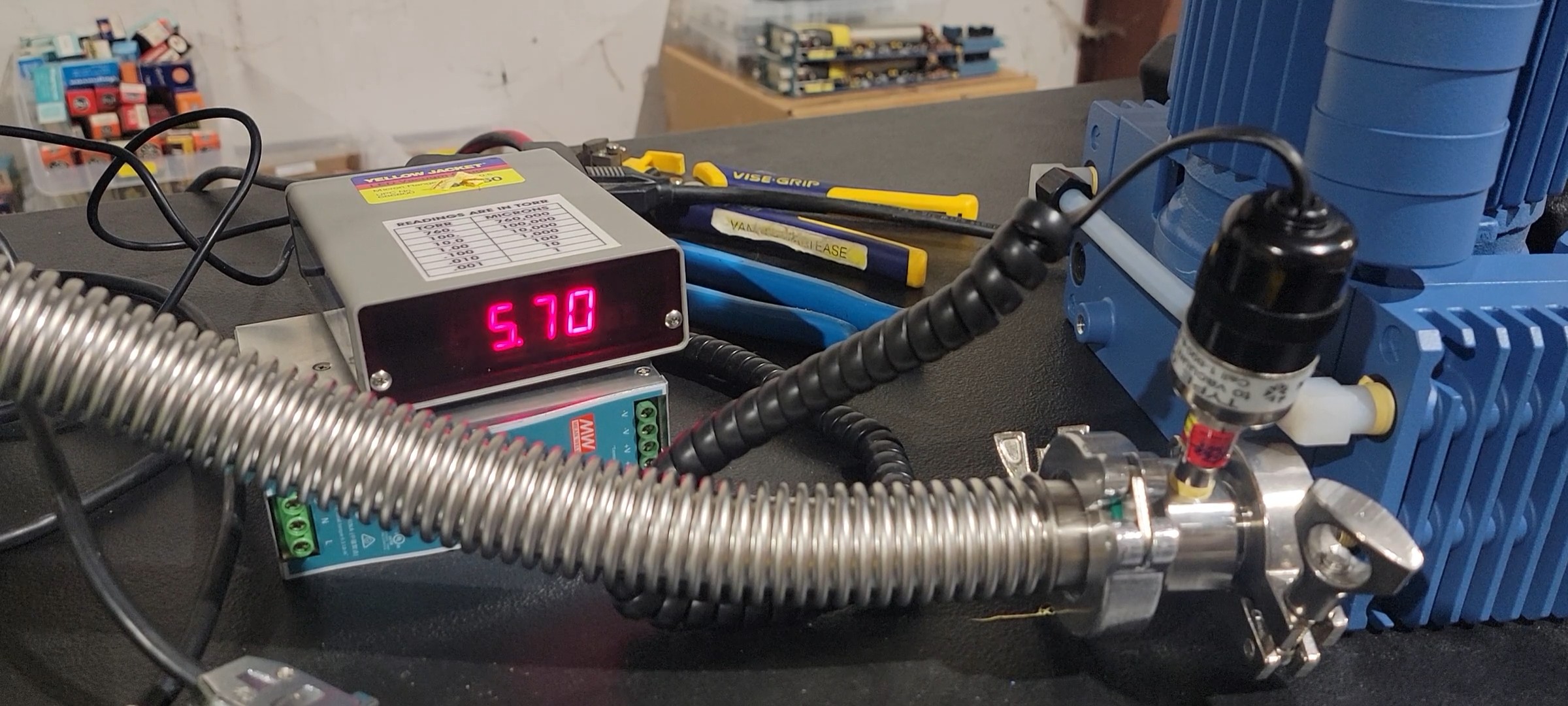

I'm going to enter this into the Hackaday Prize running and if it gets any attention, I plan to build some functional units, test them, and make the method and construction open source. My focus won't be so much on efficiency as simplicity of production. Yes, I'd like to see how well this technology works when pushed to the limits of my lab, but once we have a working device, I want to see "how low can we go?" Can you build working converters with just a blowtorch and an old HVAC pump? Maybe not, but... maybe?

Nick Poole

Nick Poole

Razvan Caldararu

Razvan Caldararu

Jorj Bauer

Jorj Bauer

zachfrew

zachfrew

Dominik Meffert

Dominik Meffert

lowering work function of the filament could also change things even though there are not many accessible materials that can do this. Also uv light will be more likely to overcome the work function but most of that is now stopped by the glass envelope. Getting over say 3-5eV of work function with thermal energy kBT is indeed very unlikely unless T is very high.