Attempting to Coreboot (or brick) e-Waste Laptops

(semi) Live documentation of the highs and lows of flashing open-source firmware to old laptops. Most likely to be a cautionary tale.

(semi) Live documentation of the highs and lows of flashing open-source firmware to old laptops. Most likely to be a cautionary tale.

To make the experience fit your profile, pick a username and tell us what interests you.

We found and based on your interests.

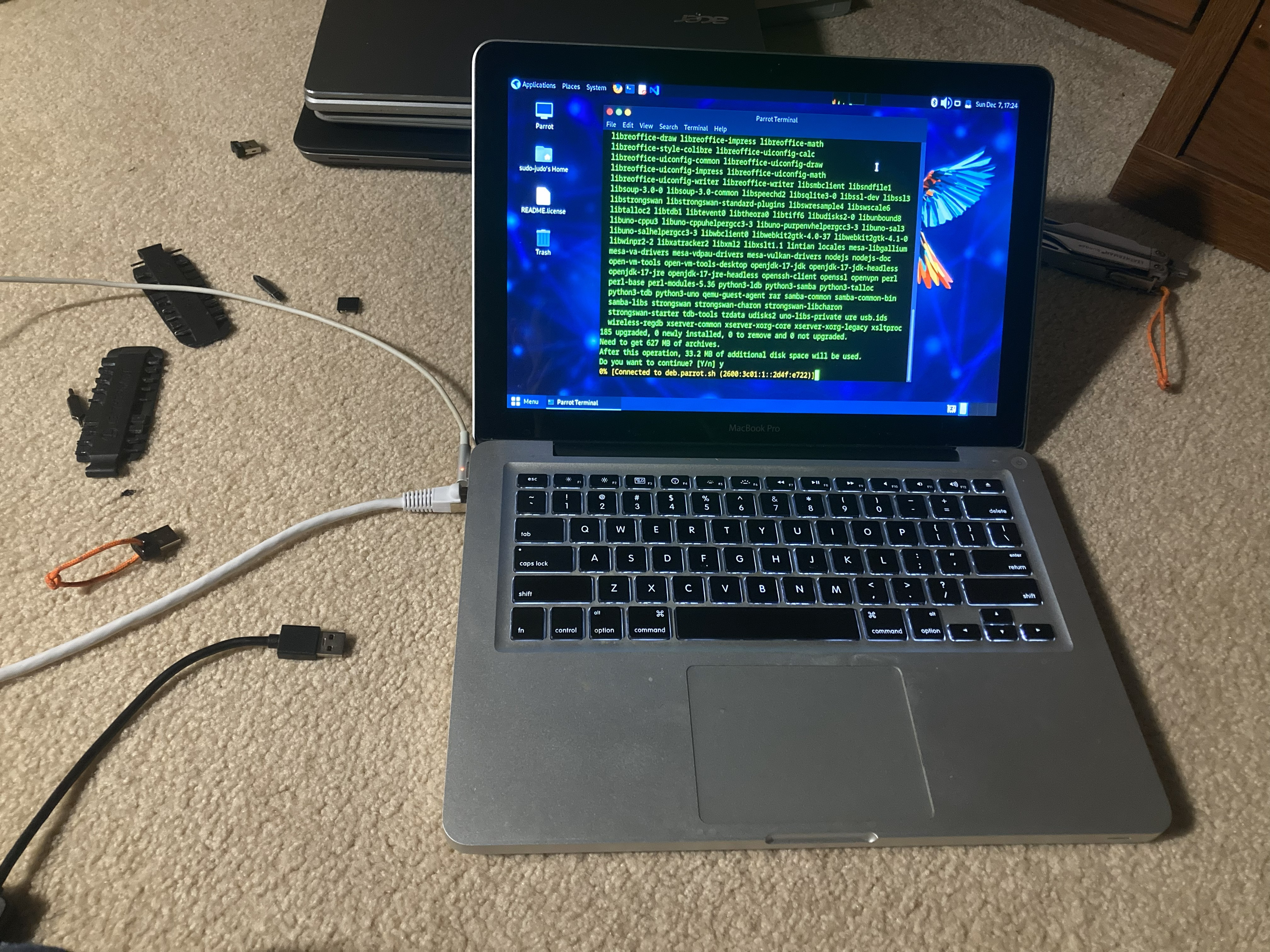

For the internal flashing process for Coreboot, the user should be running Linux on the target machine so that they can access the Shell with full system privileges, and to have access to "coreboot-utils", a package that contains the tools and dependencies for Coreboot flashing. (I'm not going to get into the specifics; use whatever floats your boat, but just know that I will be using Debian with APT) This can be accomplished by flashing Linux to a bootable USB drive, OR by flashing Linux to a hard drive and inserting it into the chassis. (Full guide below)

*In my opinion, if you are Corebooting your machine, you really shouldn't be using MacOS on it anymore. It's pretty much pointless to go through all of this trouble JUST to go right back to MacOS, with all of it's bloat and guardrails. It's like if you converted your tricycle to a mountain bike, just to add training wheels all over again.

To install Linux, you should remove the drive from the MacBook and connect it to another computer using a SATA to USB adapter, which you can find on Amazon. From there, flash the ISO of your choice using BalenaEtcher or Rufus (please message me if you need help with this) There are other ways you can do this, but the goal here is to have a drive installed in the MacBook with Linux on it.

*If you are removing your hard drive, please read this next part carefully, because Apple's hard drive enclosures are a tad bit fragile.

Step 1: Remove the backplate to access the internals. The hard drive slot is located underneath the right palmrest.

Step 2: Carefully remove the screws on the side bumper closest to the optical drive. There are two screws per bumper, one on each side. Before the drive can be removed, you need to loosen the screws and remove the bumper. We only need to remove one bumper, which is the one closest to the optical drive. Leave the other bumper inside if you would like.

Step 4: As you can see in the image below, Apple installs small cylinder-head screws into the sides of the drive. The bumper we removed is designed to clamp down on these screw heads to hold the drive into place. If you don't want your drive to rattle around inside, you need to remove these from the factory drive and screw them onto your new drive.

Step 5: Once you have transplanted the cylinder-head screws onto your new drive, you can reattach the ribbon cable and slowly lower it into the slot again. I put Linux on the drive shown below beforehand, so now all I have to do is put it inside the MacBook and boot it.

Step 6: Reinsert the bumper and SLOWLY tighten. Keep in mind that not only are you tightening the bumper onto the chassis, but the bumper is widening to squeeze the drive the more you tighten it. You should only tighten until it is snug, or it will just become a matter of which part snaps first. When done, reinstall the backplate.

Step 7: If you did everything properly, your newly-installed drive should be connected and installed properly. Now just boot up the computer, select the drive in the EFI, and cross your fingers!

At this point in time, we should have our MacBook running some version of Linux (or Arch, if that's what you REALLY want) for the next steps. If you need more help, privately message me. I am currently probing the internals in the shell so I have a baseline for the next log. I will post the next log soon, and hopefully I will include some basic probing you can conduct in the Shell with FlashROM to test your chip and back up your flash layout.

While I was setting up the MacBook, I was also simultaneously conducting research on the various flashing methods for the A1278. There were a handful of similar models between 2010-2012 that, due to differences in chip layout, had very different known access vectors for Coreboot.

For example, while the A1278 (my target machine) is considered difficult to flash externally, users have been able to reliably externally flash the A1466, which was released around the same period.

An extremely helpful reference that I used in my research was the thorough MacBook Coreboot documentation uploaded to ch1p.io written by Evgeny Sorokin (Also known as "gch1p" on GitHub) and partly by Sebastian Grzywna, (AKA swiftgeek), a Coreboot contributor.

If you are planning to Coreboot your MacBook, I implore you to read the references below:

On the current state of coreboot on MacBooks

Flashing coreboot on MacBooks without external programmer using IFD hack

This documentation was extremely helpful and provided a great amount of insight into dos and don'ts of the flashing process. It stopped me from attempting an external flash that would have damaged the Logic Board beyond repair and potentially bricked the laptop. This project would probably not be possible without the documentation as a guide.

In this log, I will give a brief summary of each known flashing method's status on the Macbook A1278, using information from ch1p.io and from various internet sources.

MMGA

MMGA was a bash script written by Evgeny Sorokin, designed to be used to automate internal flashing of Coreboot without attaching an external programmer to the motherboard. Sorokin has stated multiple times both on GitHub and on ch1p.io that he does not recommend its use, particularly because many users saw it as a simple script that would automate the entire Coreboot process for them, and didn't pay attention to the rest of the warnings in his documentation and information needed to make it work properly. As a result, some people who used MMGA may have bricked their laptops because they trusted MMGA to automate everything for them. It is for this reason that Sorokin has recommended MANUALLY running the commands in MMGA ourselves through Internal Flashing.

INTERNAL FLASHING

Internal Flashing on MacBooks is essentially flashing Coreboot to the motherboard without having to take it apart and attach an external programmer. According to Sorokin, it can be accomplished on some MacBooks (including the A1278, my target machine) with just Linux installed and root access. In Sorokin's process, the Intel_ME region on the target firmware chip is read using a bash application called "FlashROM", then shrunken from 8 Megabytes to only 90 Kilobytes using a Python script called ME_Cleaner. From there, the remaining space can be used to flash Coreboot to the chip.

EXTERNAL FLASHING

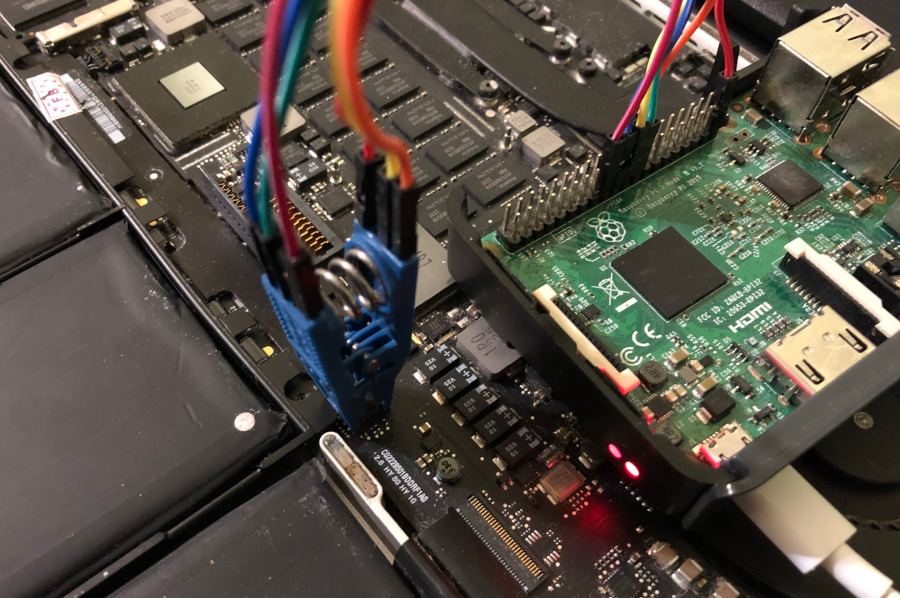

External flashing typically involves taking apart the computer itself to gain access to the motherboard (or Logic Board, as Apple calls their motherboards) and attaching an external programmer. (example: Raspberry Pi) Typically, an external programmer can be connected to a motherboard's BIOS/UEFI chip or the specific target chip with an SOIC clip that latches onto the chip legs to ensure a strong connection to the chip. From there, the clip can have jumper wires connected to it that run into an external programmer (there are lots out there) or a Raspberry Pi, to flash the payload onto the chip.

For my target machine, the MacBook A1278, external flashing is very difficult and not recommended. The components surrounding the target BIOS/UEFI chip are...

Read more »This log will continue to be updated on a semi-regular basis as this project progresses*

The first machine that I will be attempting to Coreboot is a 2010 Macbook Pro, 13" Unibody shell. By factory default, it boasts an Intel P880 "Core 2 Duo" processor, 4 gigabytes of installed DDR3 SDRAM, a 320-Gigabyte HDD, and an Nvidia GeForce 320M GPU. The laptop also comes with a backlit keyboard, a multi-touch glass trackpad, and as Apple called it: a "glossy" display with 1280x800 native resolution.

The model number is specifically the A1278, also known as A1278-2531 or Macbook (8 ' 1) respectively.

The full technical specifications can be found here. Keep in mind that there are multiple nearly-identical models manufactured in both 2010 and 2011, with slightly different technical specifications. The website linked has a far more detailed summary of the specifications of this particular model.

This particular MacBook I was using had not booted in over 7 years. It was covered in a layer of dust, but when I opened the lid, the keyboard and screen were surprisingly clean. I found the MagSafe charger next to the MacBook and plugged it in. After letting it charge for a few minutes, I pressed the power button, and it booted up perfectly with the classic Mac chime!

The MacOS desktop took a little while to load, but it booted without any issues! Obviously, because it is such an old laptop, it had a difficult time opening and closing apps, but it ran Mac OS surprisingly well. All of the icons and animations still worked, it just had trouble opening anything in under 30 seconds.

In addition to Coreboot, (if this flash is successful) I will also be installing an SSD with a lightweight Linux distro to significantly improve the speed and snappiness of the Mac. (I don't use Arch by the way)

(I tested TAILS as it was the only boot drive I had on hand, and it ran butter smooth without issue through the USB 2.0 port. If I use this as a daily driver Linux machine I will probably use Zorin, Mint, or another Debian distro)

After consulting Apple's forums, I found a quick method to reset the password by invoking the command "resetpassword" in the Bash Shell while the Mac was in Recovery Mode, which can be accessed by holding down the "options" key immediately after booting.

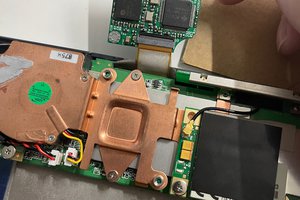

It took a while to find the chip based on the motherboard's model number, but after referencing some technical resources, I found the location of what is listed as the BIOS/UEFI chip on the motherboard.

Here are some images of the BIOS/UEFI chip that I took, with a penny for scale.

This log will continue to be updated on a semi-regular basis as this project progresses*

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.

Thank you for the comment! You are actually the first person to comment on any of my projects! I just read through your Chromebox project - I haven't seen many people put OpenSUSE on computers; I might give it a try one day.

This project just serves as documentation for anyone who is looking into Coreboot. Most of the Internet guides for Coreboot flashing have very vague instructions, and a lot of previous knowledge is expected. I want to log each step I take so that even if I am not successful, someone can learn what NOT to do. If I am successful, I can clean it up into a step-by-step guide for the specific models.

Become a member to follow this project and never miss any updates

Greg Duckworth

Greg Duckworth

flip

flip

Wenting Zhang

Wenting Zhang

Should be interesting to follow, though I have no target hardware. It turns out that the https://docs.mrchromebox.tech/ MrChromebox bootloader I used in #Restoring an Asus Chromebox CN60 is based on Coreboot.