-

Auto-cropping scanned negatives with OpenCV

02/16/2019 at 08:12 • 4 commentsWith the number of negatives I've scanned, manually cropping each and every one image down to the exposed part of the film is pretty tedious. Over the last couple of days I've been hacking together a solution for taking a scanned negative from Adobe Lightroom, detecting the bounds of the exposure using OpenCV, and pushing that crop information back into Lightroom.

This is a fairly straight forward image processing problem, as most images have an obvious edge between the unexposed film and the exposed part. I chucked together a script in Python that uses a simple brightness threshold to look for this:

![]()

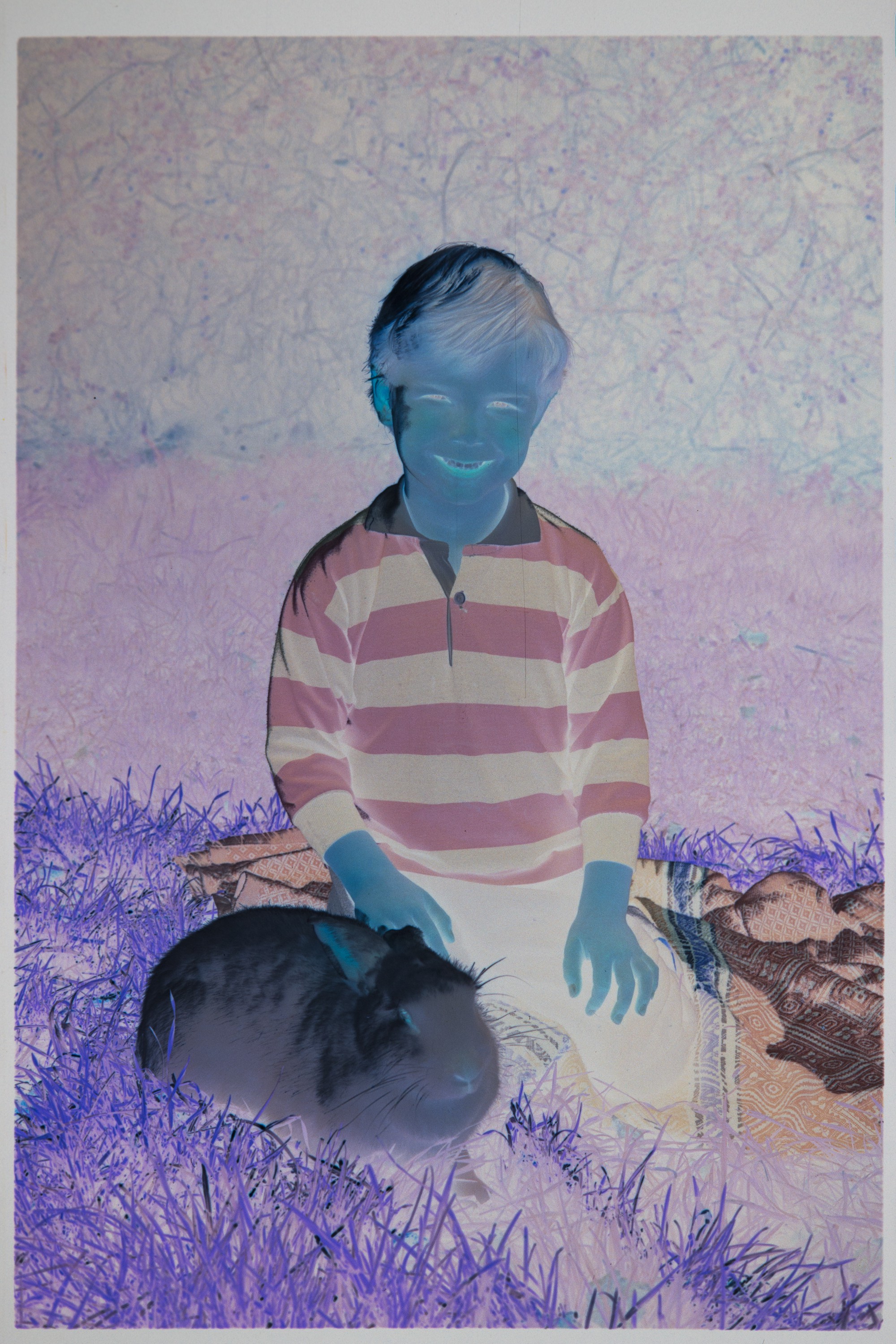

Oh hey, it's me in 1996 ![]()

Exposure area detection using a brightness threshold Once the bounds of the frame are known, there's a few small adjustments to improve it. The edge is inset slightly to make sure the crop doesn't contain any (partly) unexposed film, and the crop rectangle is adjusted to have an exact 3:2 aspect ratio. Once that's done, there's a bit of fiddling to turn it into four 0.0 - 1.0 range edge offsets that Lightroom understands.

![]()

Crop detected using OpenCV. The blue line is the detected frame, and the green line is the final crop. The green dot is a sniper. ![]()

Crop applied in Lightroom and developed to a positive. Writing a Lightroom plugin to glue this together was a gigantic pain as the Lua API for Lightroom is poorly documented, and its plugin system is designed only for export plugins (eg. posting to a new social network), but the result was worth it:

![]()

Demo of integration with Lightroom 6 (and a slightly more challenging image). To trigger this, I use File -> Plug-in Extras -> Negative Auto Crop The detection process I have at the moment works on most images, but as it looks for the biggest single blob/contour, it fails on images with over or under exposed parts that cross the full width or height of the frame. I'm looking at running a few different passes to resolve this. Underexposed images don't process very well as they have low (or no) contrast between the exposure and the rest of the film.

Currently the resulting crop is the median of all rectangles over a minimum size. These are the green rectangles in the gifs above (the red rectangles are too small and are ignored).

To prevent light shining through sprocket holes from affecting the frame, the brightest pixels in the image are masked out during thresholding. The darkest pixels probably also need to be ignored to stop dark marks on the film being included as an edge.

Here's the code at the time of writing.

-

Colour negative processing

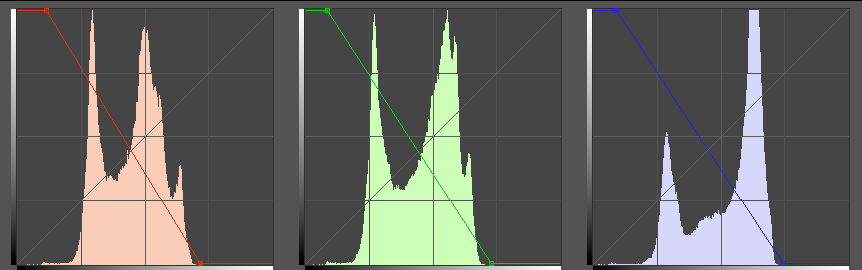

02/13/2019 at 08:01 • 0 commentsUp until now I've been manually processing my scanned negatives into positives simply by fiddling with the RGB curves.

The process is roughly to invert the R, G, and B curves, then move the white and black points to cancel out the the different response of the film to red, green and blue:

![]()

After 10 minutes of tweaking, adjustment layers and comparing to a reference image, I would have something that looks kind of ok, but the colours were always way off vs the reference print, hence why I haven't written about this process.

The problem with this approach is that it's very unscientific; it's all done by eye, and manipulating the curves tool with the mouse is imprecise. I tried out the Photoshop plugin Color Perfect a while ago which was better, but a high price tag combined with a terrible UI stopped me purchasing it.

I looked into writing a Lightroom plugin to automate this conversion process, but it turns out someone else has written a plugin with the same idea called Negative Lab Pro. I haven't bought this yet, but the results it gives are fantastic:

![]()

Original lab scan from a Noritsu Koki QSS. Click for 1.5MP original (0.5MB) ![]()

DSLR scan processed using Negative Lab Pro. Click for 18MP original (11MB) For comparison, here are the two scans I've had done professionally of this negative, and my best manual curves attempt (right):

-

Professional scan comparison (part II)

01/19/2019 at 00:29 • 0 commentsAfter recieving borderline results from a professional film scan in the last post, I took the same negative to be scanned at Wellington Photo Warehouse, another local store.

The scan quality this time around was significantly better. The scan was delivered at the same resolution in both JPEG and TIFF (8-bit, but still nice to have), and it cost just $5 - one third of the price per frame compared to the previous store! Here's the result:

![]()

19MP scan from unknown equpment at Photo Warehouse. Click for full-size original (9MB) The delivered JPEG file has no EXIF data so I don't know what equipment this was scanned on, but the guy I talked to on the phone before going in said they didn't use a drum scanner or flatbed. He described it as a "transmission scanner" with a light source on one side of the film and a CCD on the other, though that doesn't narrow down the equipment.

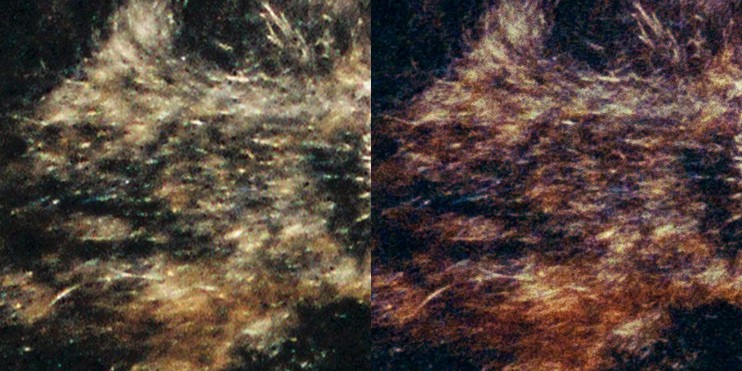

Detail-wise, I'd be happy to scan negatives in bulk at this store if I was going to pay someone to do it. My DSLR scan (left) still appears to have resolved a little more detail, but this professional scan is very close (center). Certainly a lot closer than the previous professional scan (right):

![]()

100% crop of DSLR scan (left), Photo Warehouse scan [unknown equipment] (middle), and the Fuji SP-3000 scan from the previous post (right). The crop of both professional scans was about the same at 5% loss of the exposure vertically and horizontally. I don't know what the industry standard crop is for printing 6x4's, but I suspect it's something around this number for practical reasons. I digitally cropped the DSLR scan as close to the edges of the exposure as possible, which is kind of cheating:

![]()

Photo Warehouse scan aligned over DSLR scan - roughly a 95% crop of the full exposure It would be nice to have this negative scanned on some other professional equipment to continue comparisons, but with the results I have so far I'm happy that this DSLR + macro lens setup at least matches the resolving power of the equipment I'd otherwise be paying per frame to use.

Next up I have to sort my colours out.

-

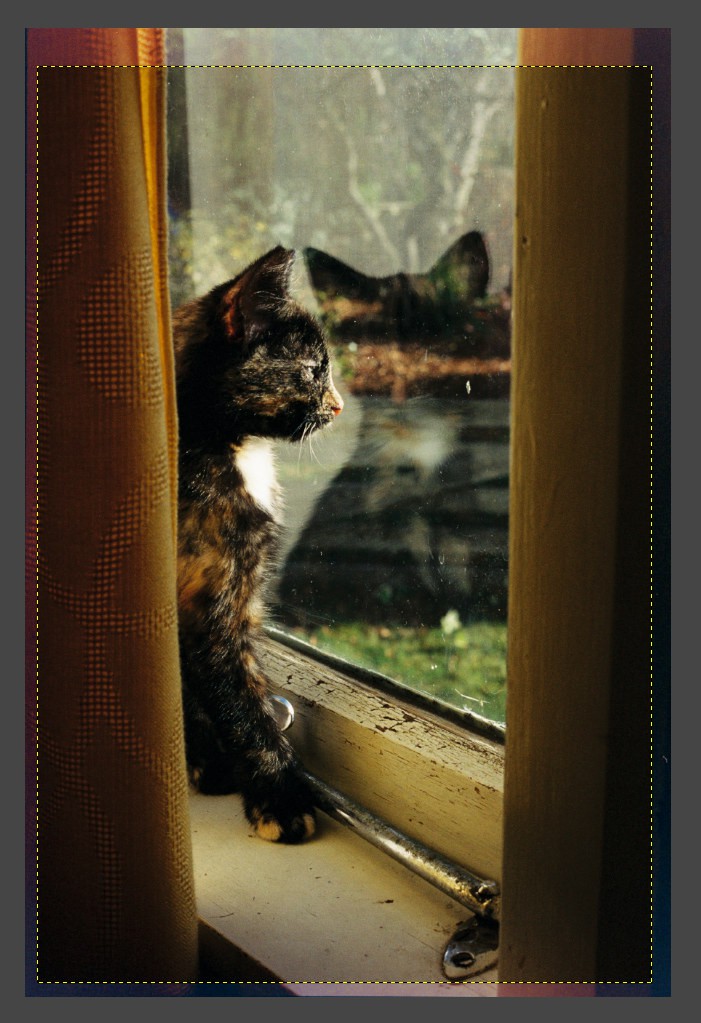

"Professional scan" comparison

01/11/2019 at 06:36 • 0 commentsAs a follow-on from the last post, I took the tortoiseshell cat negative to be scanned professionally at a local business. After a week of waiting, I eagerly went to pick it up today - they'd sent it to a different location to do the super-high resolution scan, so the wait was longer than usual.

![]()

According to the EXIF data, the scan was made with a Fuji SP-3000, which is a fairly well regarded piece of equipment. I held my breath and opened the file, ready to be blown away by a superior scan...and was pretty disappointed:

!["Super-high resolution" 35mm film scan from Wellington Photographic Supplies (WPS) "Super-high resolution" 35mm film scan from Wellington Photographic Supplies (WPS)]()

19MP scan from a local store. Click for full-size original (6MB) For reference, here's the full-size DSLR scan (10MB) ![]()

Wellington Photographic Supply Fuji SP-3000 scan. ![]()

Noritsu Koki QSS scan from 2002. I'm not concerned with the different colour - the original image has a strong yellow cast from the sunset, so it was probably corrected automatically or manually with good intent. The problem is that while this image looks alright scaled down, at 100% it's lacking a lot of detail compared to the DSLR scan:

![]()

Fuji SP-3000 (left) lacks detail compared the DSLR scan at a similar resolution (right) ![]()

![]()

I initially thought this might be partly caused by JPEG compression as the file provided was only 6MB, but had to save my DSLR scan at 0% JPEG quality to get a similar looking result:

![]()

Left: 100% JPEG quality DSLR scan. Center: same image at 0% JPEG quality. Right: image from store. What next?

I've contacted another local store that I've seen decent scans from in the the last few years when getting film developed. I'll take this same negative in to be scanned tomorrow and see if we can get a better result from them.

-

Comparison of DSLR to dedicated film scanners

12/20/2018 at 07:19 • 1 commentTo give an idea of scan quality with a DSLR, here's a comparison against a negative scanned with a consumer-grade film scanner and another scanned with a professional film scanner.

Basic consumer film scanner

This Endeavour "Personal Film and Slide Scanner" belongs to a family friend. I'm not sure of its history, but it looks like it was purchased around 2013 for the $149 NZD stickered on the box. This one has a 5MP CMOS sensor, similar to devices that can be picked up online currently for around $60 NZD.

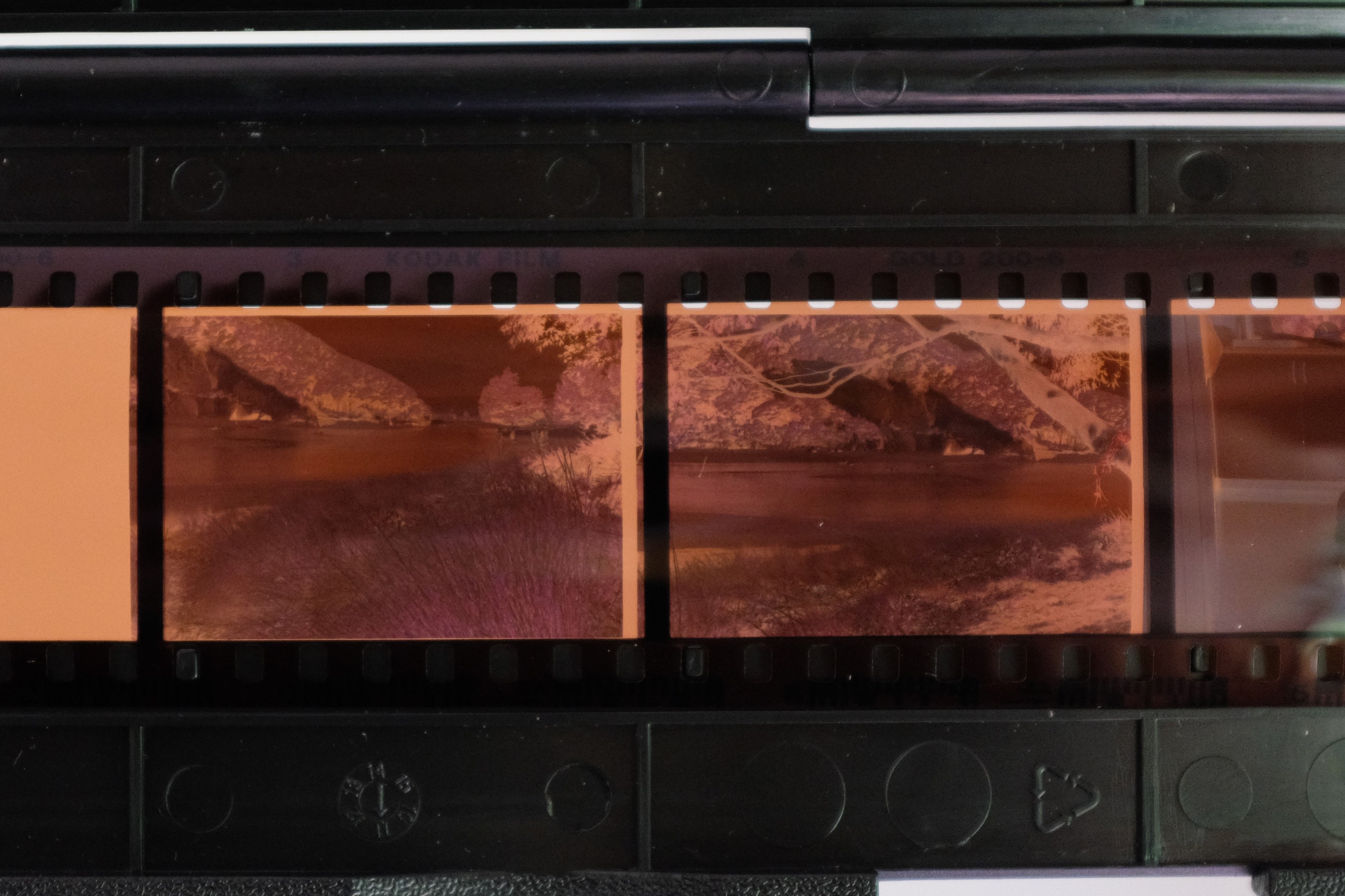

![]()

The negative I chose for this comparison was simply the first I could find that wasn't of people, as I'm in the middle of scanning my girlfriend's family photos. By chance, this roll happened to be an example of exposures not aligning with this scanner's style of mount. The images on the film aren't aligned with the sprocket holes as the mount is designed, so part of the exposure is obscured by the mount:

![Frames not aligned to sprocket holes Frames not aligned to sprocket holes]()

Scanning the left-hand exposure with the Endeavour gave this result:

Scan from the 5MP Endeavour "Personal Film and Slide Scanner". Click for full resolution. The same exposure captured through my DSLR + macro lens setup and processed to a positive manually looks like this:

![]()

Scan from Canon 70D (17.8MP after cropping). Click for full resolution. Neither of these get the colour quite right (colour is something I'm still getting the hang of in my processing), but what struck me was how much of the image is cropped out using the consumer-grade scanner. You can see that even if the film was aligned correctly in the mount, a decent chunk of the edges would be lost:

![]()

The original exposure isn't a particularly high fidelity or technically good, but comparing detail between the two scans, I would say the Endeavour is simply not useful outside of quickly emailing an old picture to a friend for laughs:

![]()

Left: 5MP dedicated film scanner. Right: Scan from Canon 70D scaled down to 5MP. I've recently seen devices like this with 14MP sensors on AliExpress, but I suspect at this price-point the image quality would still be ultimately limited by the size and quality of the lens inside.

Professional film scanner

The mail-in developing service FotoPost we used in the early 2000's used a Noritsu Koki QSS to scan the images sent back on CD, according to EXIF data. The exact model of scanner isn't specified, but the image quality really speaks for itself:

![]()

1.5MP image from a Noritsu Koki QSS in 2002. There's a ton of detail here, despite the low resolution output. The same negative scanned by my Canon 70D looks like this when roughly matched for colour and scaled down to the same resolution:

![]()

18.9MP scan scaled down to 1.5MP to match the FotoPost scan. Click for the full resolution version (10MB) I've just re-scanned this negative for this post as I found the original scan from a year ago was slightly out of focus while processing it. Even with the correct focus, this DSLR scan seems a tad softer than the FotoPost version. The cat's cheek has more hair detail visible in the FotoPost scan, though at the closest focusing distance I still couldn't resolve this detail, so it may be a result of the image processing or just too small for my lens to resolve:

![]()

Modern professional scanner?

To continue this comparison post, I'll have this same negative scanned at 18MP by a local service once I'm back from Christmas break. It costs $15 NZD for a single scan at this resolution, but it will give an idea of how much or little I'm missing out on by scanning these myself.

Continued in: "Professional scan" comparison

-

Scanning 35mm film with a DSLR

12/19/2018 at 03:23 • 0 commentsHere's a quick run-down of how I've been scanning negatives.

Camera settings

- Aperture priority mode with no exposure compensation. With my light source, shutter speeds range from 1/100s to 1/1000s depending on the exposure of the frame being captured.

- Aperture at f8.0 to give good sharpness and provide a small margin of error for getting the focus right.

- Lens set to manual focus, with image stabilisation turned off.

- White balance manually set for the light source.

- Shutter triggering with an infrared remote trigger to avoid touching the camera and adding vibration.

Framing and alignment

How much the negative image fills the frame is a balance between resolution and the speed you want to work. I've found the sweet spot for me is framing so the sprocket holes barely enter the frame. This makes it quick and painless to get each frame aligned to capture, and leaves the final crop and any minor straightening for processing later.

![]()

Framing example. After cropping 75px off the top and bottom, and 120px off the left and right , the final image is around 18MP. I did experiment with filling the whole frame in-camera, but I found it wasn't worth the extra time and precision needed for a small gain in final image resolution.

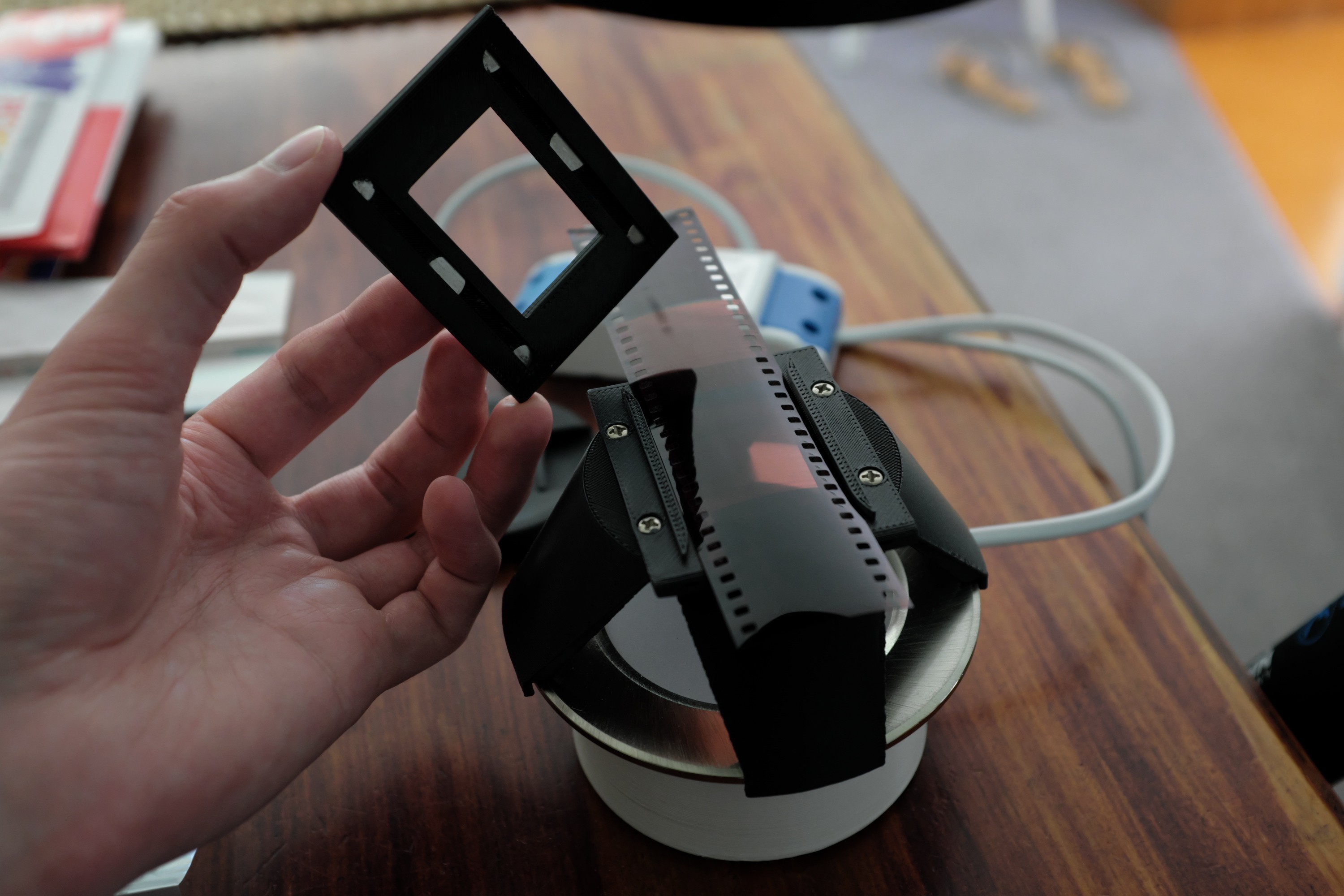

Feeding film

With my mount, I take the top plate off completely to insert a new section from film the top, then place the top plate back on. To move between frames the top plate is levered up slightly to release pressure, then the film can be slid along:

![]()

It's easy to do this with the remote trigger still in one hand, so it's a pretty quick cycle to capture each frame. Once focus is established for a roll, I use live view to quickly get each exposure framed without looking through the viewfinder again.

Focusing

I currently prefer to set focus through the viewfinder by eye, as it's easy to see when peak sharpness is reached across the whole image. Generally I found re-focusing at the start of each new roll was necessary, and more often if the image sharpness looked questionable.

During the first batch of scanning I did, I used the 5x and 10x zoom function in live view to focus on features or grain, but this frequently resulted in incorrect focus and was more time consuming than looking through the viewfinder.

Trying to set focus on a frame that is out of focus itself (or has motion blur) is difficult. I'd recommend setting focus for a roll using a photo that has a fine texture in focus (eg. hair, gravel, grass, carpet). I tried the camera's auto-focus in both in viewfinder and live-preview mode, and neither gave reliable results for me. The focal plane is tiny, so you really need to dial it in manually. Auto-focus would usually focus on marks and dust on the surface of the film rather than on the image in the film's emulsion layer, and it would move slightly with each exposure, even if the focus was already spot-on.

Ambient light

I was originally working in a room with the lights off and curtains drawn, but I've found some ambient light has no adverse effects (as long as there's no direct sunlight or overhead lights). It's much more comfortable to work in a room where you can see!

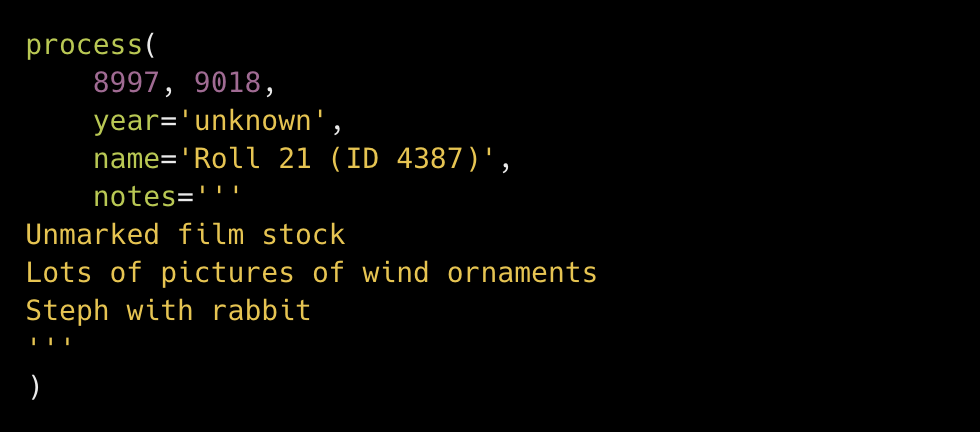

Organising image files

To avoid going back to a computer constantly, I note the start and end image number on the camera for each roll as I'm working, along with any available information (date, film stock, descriptions). Eventually when the SD Card is inserted into a computer I run a hacked-together script to use this information to move the images into folders:

![]()

Recording roll information as a series of function calls that can be executed later to move the images . It could be better, but it works well enough copy-pasting this for each roll. Notes are dumped in a file alongside the images. I like to have one folder per roll of film, grouped by year:

Film Negatives/[year]/[roll name]. Where the year of a roll isn't clear I'll use "unknown" or a partial year like "199x". If none of the rolls have useful names, an incrementing scheme like "Roll 1", "Roll 2" is the only sane option. Including the strip's random ID in the name is useful if the roll needs to be located again in future. -

Light source for scanning film

12/18/2018 at 03:31 • 0 commentsDuring early testing, I figured out a couple of criteria for the light source:

- The film has to be mounted away from the light source's diffuser so that any texture in the diffuser is not visible in the final image (ie. very out of focus).

- The light has be bright enough to obtain a shutter speed of at least 1/100s at when stopped down to the lens's sharpest aperture to prevent any vibration creeping in and blurring the image.

I browsed local stores and ended up picking this Deta 12W Daylight LED down light from Bunnings as it was bright, had a decent looking diffuser and in testing showed fairly even illumination across the whole surface.

This apparently has a Color Rendering Index (CRI) of 86, which is fairly decent given the price. I'm unsure exactly how this affects imaging compared to a continuous light source like an incandescent bulb.

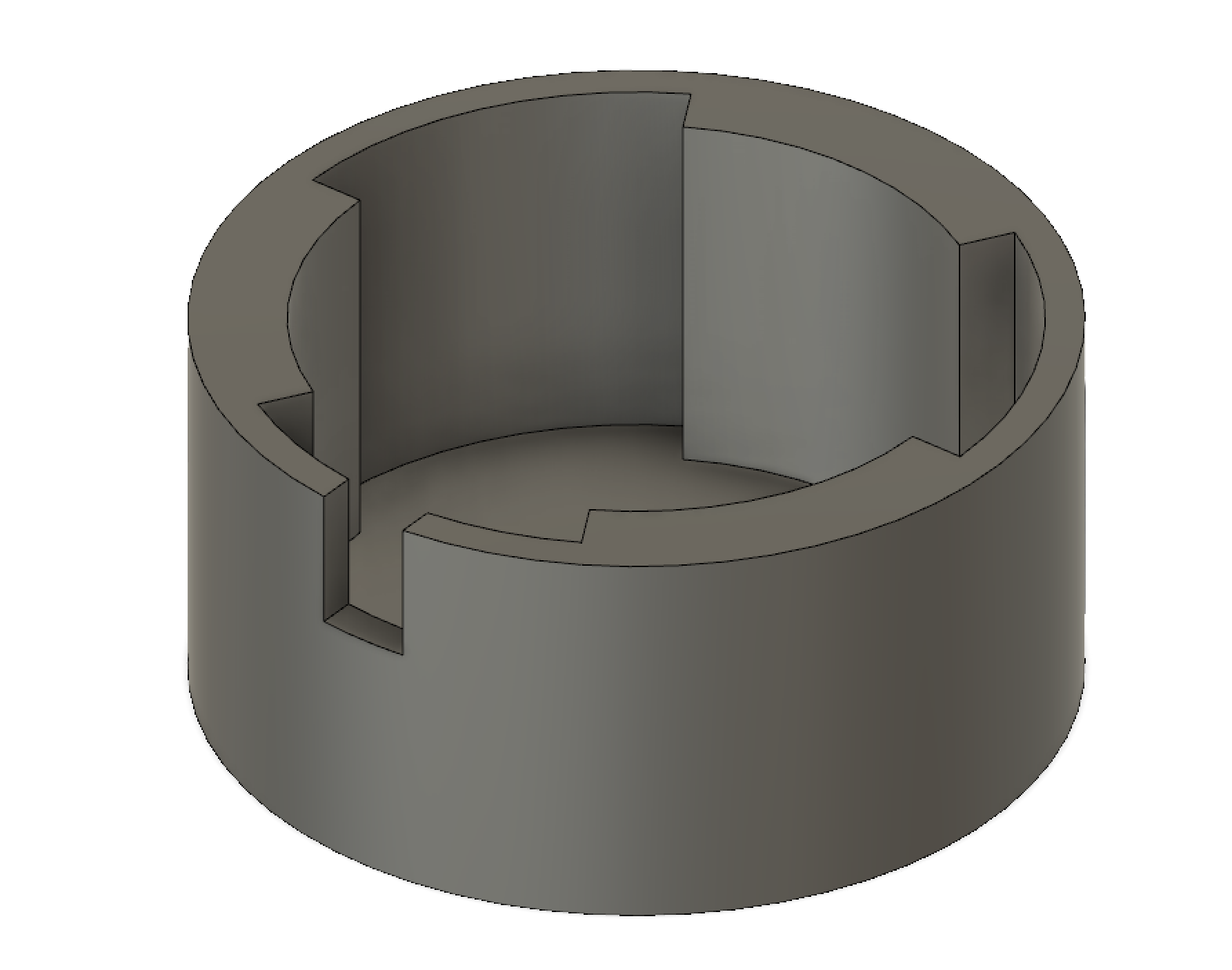

![]()

With the dimensions of the light known, I chucked together a friction-fit / clip-on adapter for the bottom plate to screw to that puts 5cm between the film and the diffuser of the light:

![]()

Then a quick case to mount the light facing up:

![]()

All together, this completes the setup with no moving parts:

![]()

The whole setup is heavy enough that the top plate can be lifted off without disturbing the other half, and rubber feet added on the light case stop it sliding around.

This rig has been fantastic to use for hours on end without causing any frustration. The only thing I'd probably change in a future revision is making the attachment to the light more secure; the friction clip/fit is acceptable, but having screws to keep it exactly in place would help.

All CAD files are available to download on the project's main page.

-

Film scanning mount design

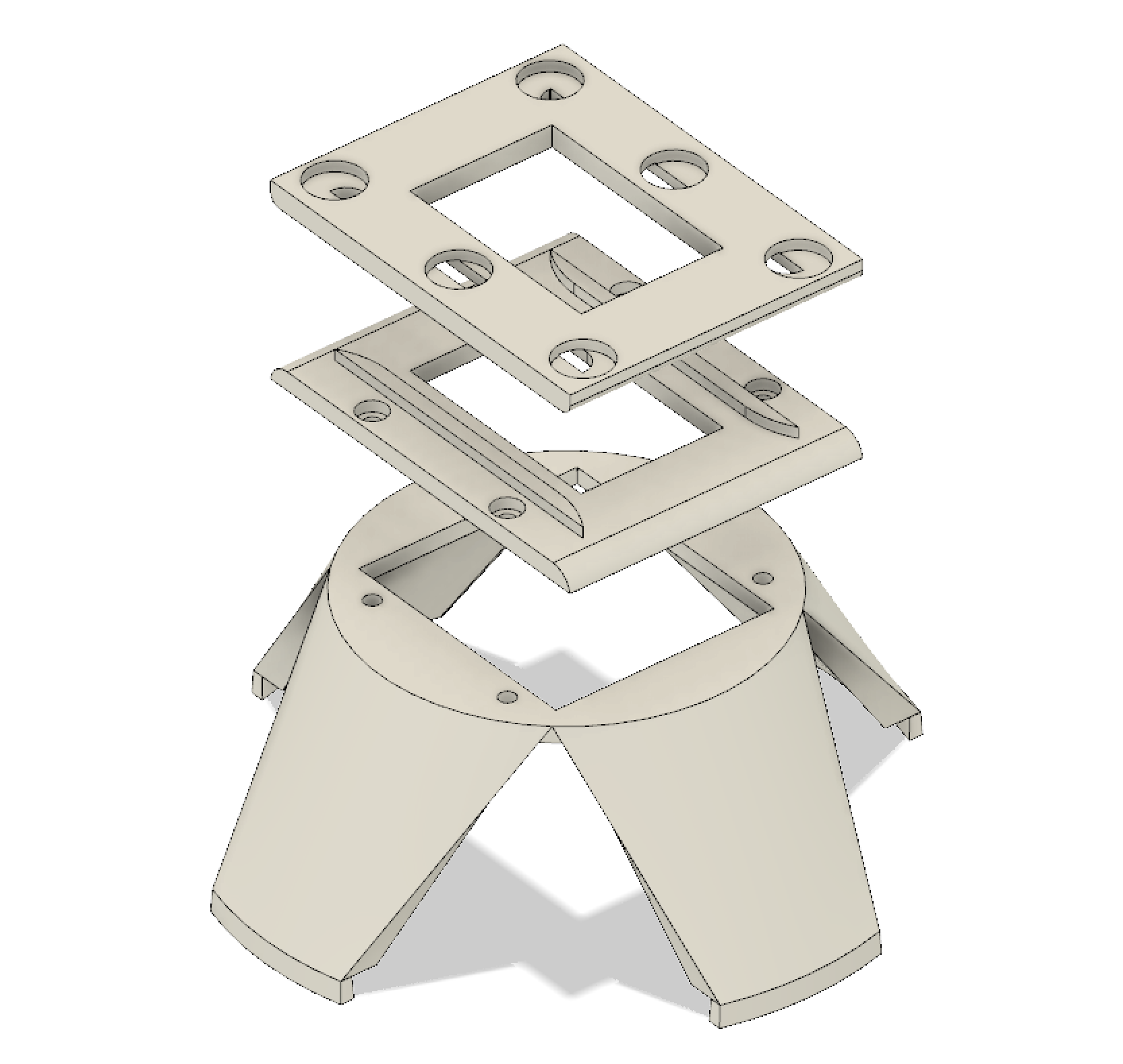

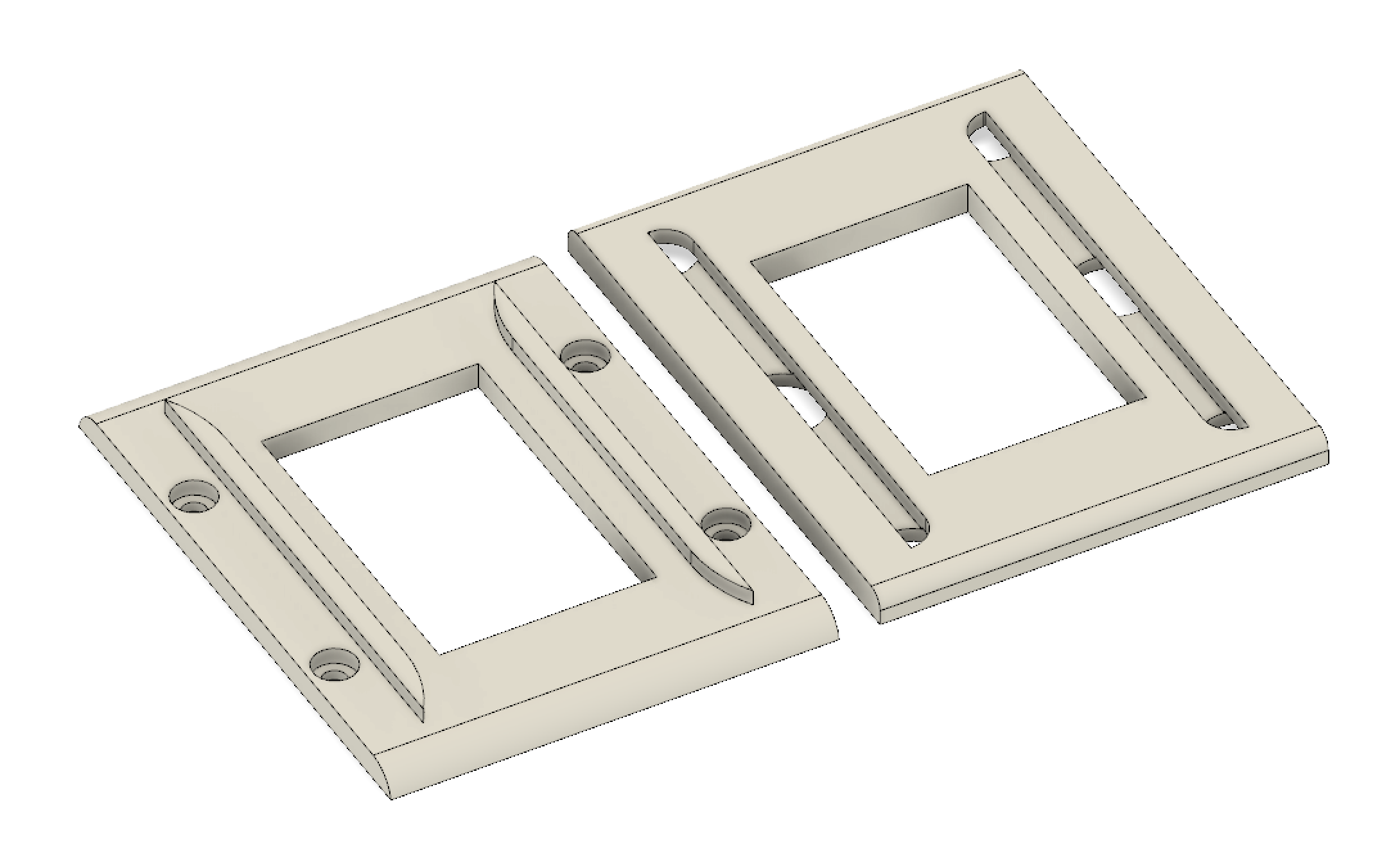

12/18/2018 at 01:33 • 0 comments![]()

35mm film tray from a dedicated film scanner. Both cheap and expensive scanners use mounts like this. The Film Toaster and flatbed scanners also use a similar mount. I trialed a dedicated negative scanner before starting this project and found that the trays it used were quite fiddly and somewhat fragile. They do make it quick to move between frames, but opening and closing them to change the film was tedious in my experience. Designs like this also assumes frames are properly spaced on the film, which isn't always the case.

Based on this, I had a few criteria for a custom design:

- Easy to insert and remove film without catches, latches, etc

- Easy to align film for scanning

- Simple mechanism to apply and remove pressure once aligned to keep film flat

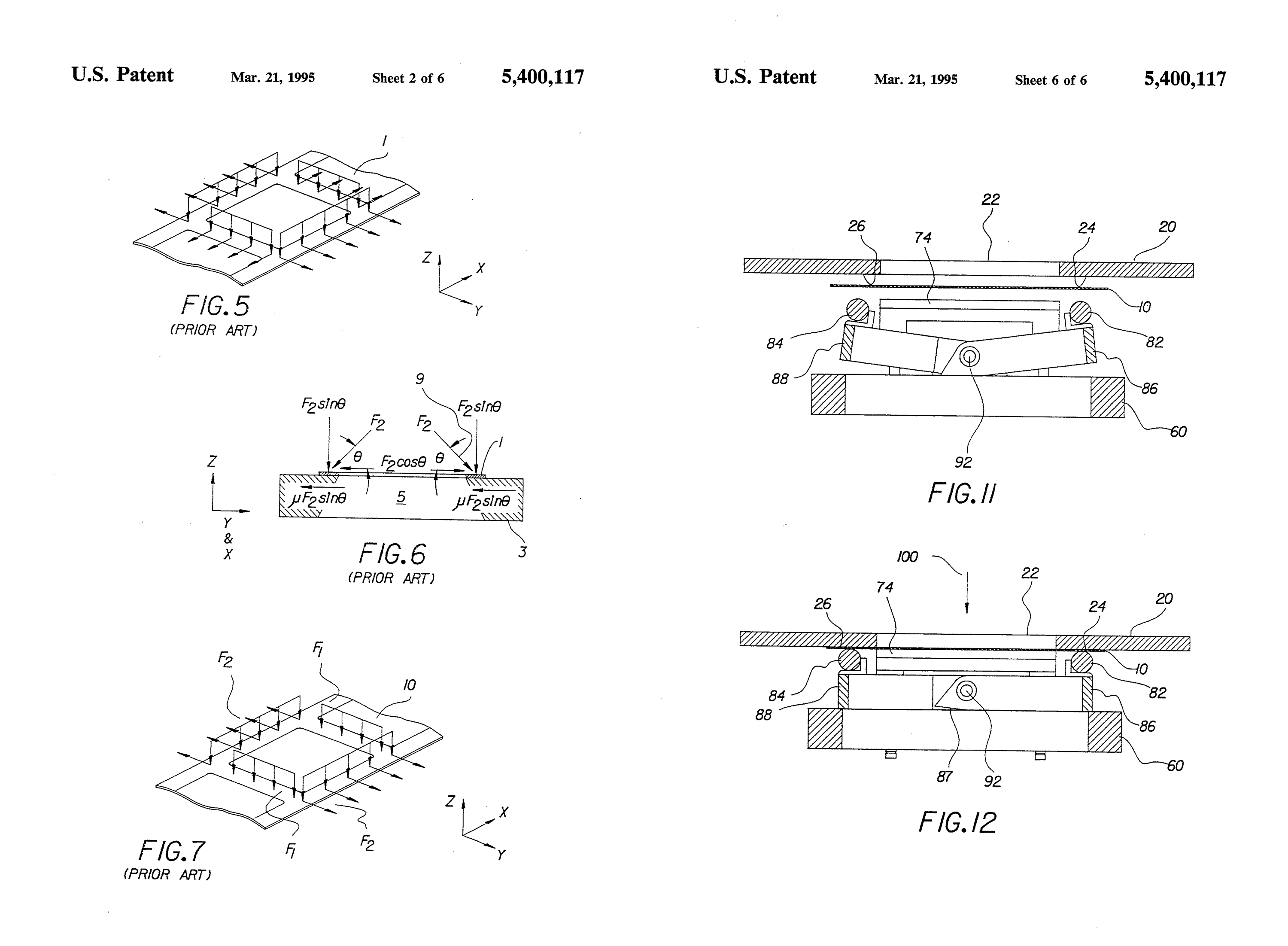

Looking at patents for ideas on how existing high-speed film scanners might handle this, I came across US5400117A: "Film clamp for flattening image frames in a scanning gate":

A film flattening apparatus and method of operation for flattening a filmstrip image frame against an aperture in a base operable by applying normal compressing force through longitudinally extending clamping elements to compress the longitudinal edges of said filmstrip image frame against said base surface...

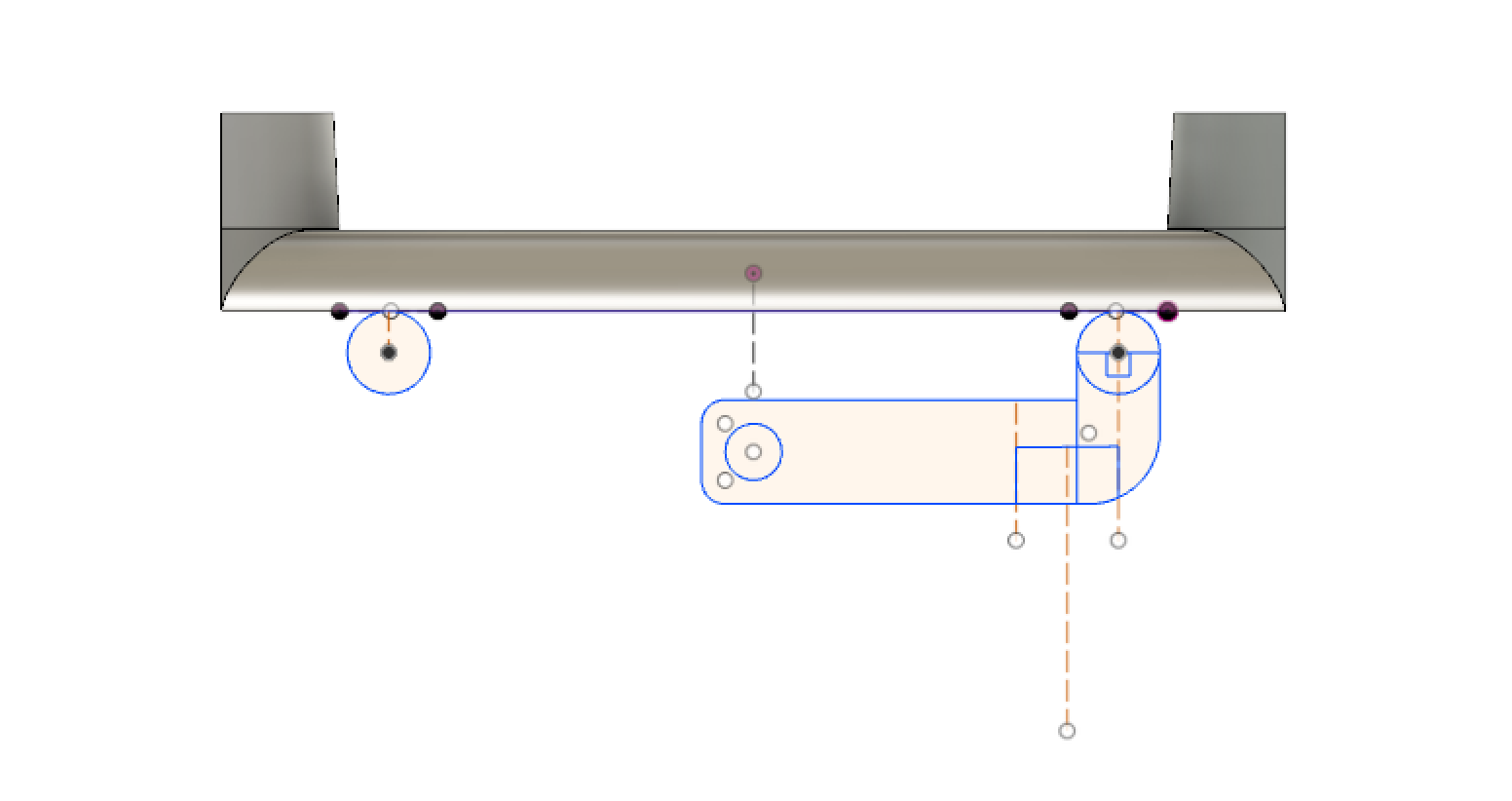

![]()

This design has some good ideas, but armed with just a 3d printer, some hand tools and very little experience in mechanical engineering I wasn't sure how I was going to construct something reliable enough with a lever to apply pressure to the film:

![]()

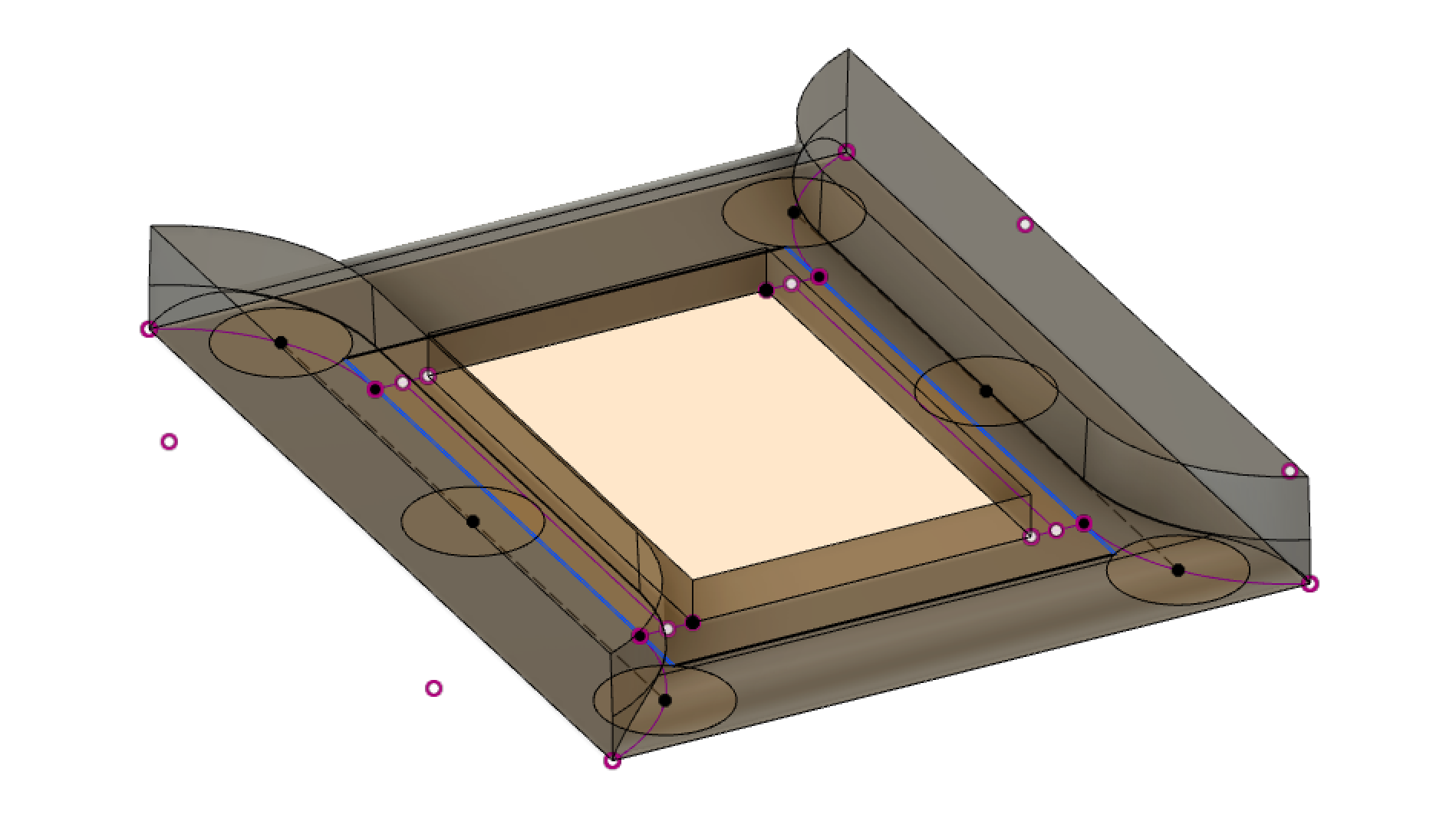

Help..? By this point I'd sketched out a guide and aperture to fit 35mm film, but wasn't sure where or how to apply moving parts. After at least a week of mulling over how I was going to make this mechanical contraption work, I found myself fiddling with some small neodymium magnets I'd bought for a different project. It was only then it occurred to me that I could keep the clamp extremely simple just by using magnets to apply force - no levers, hinges or springs required:

![]()

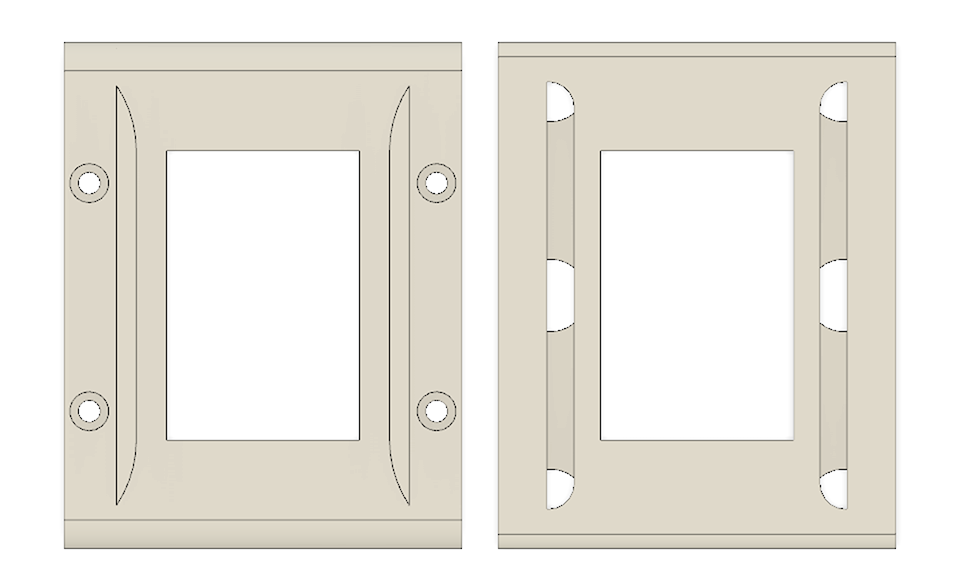

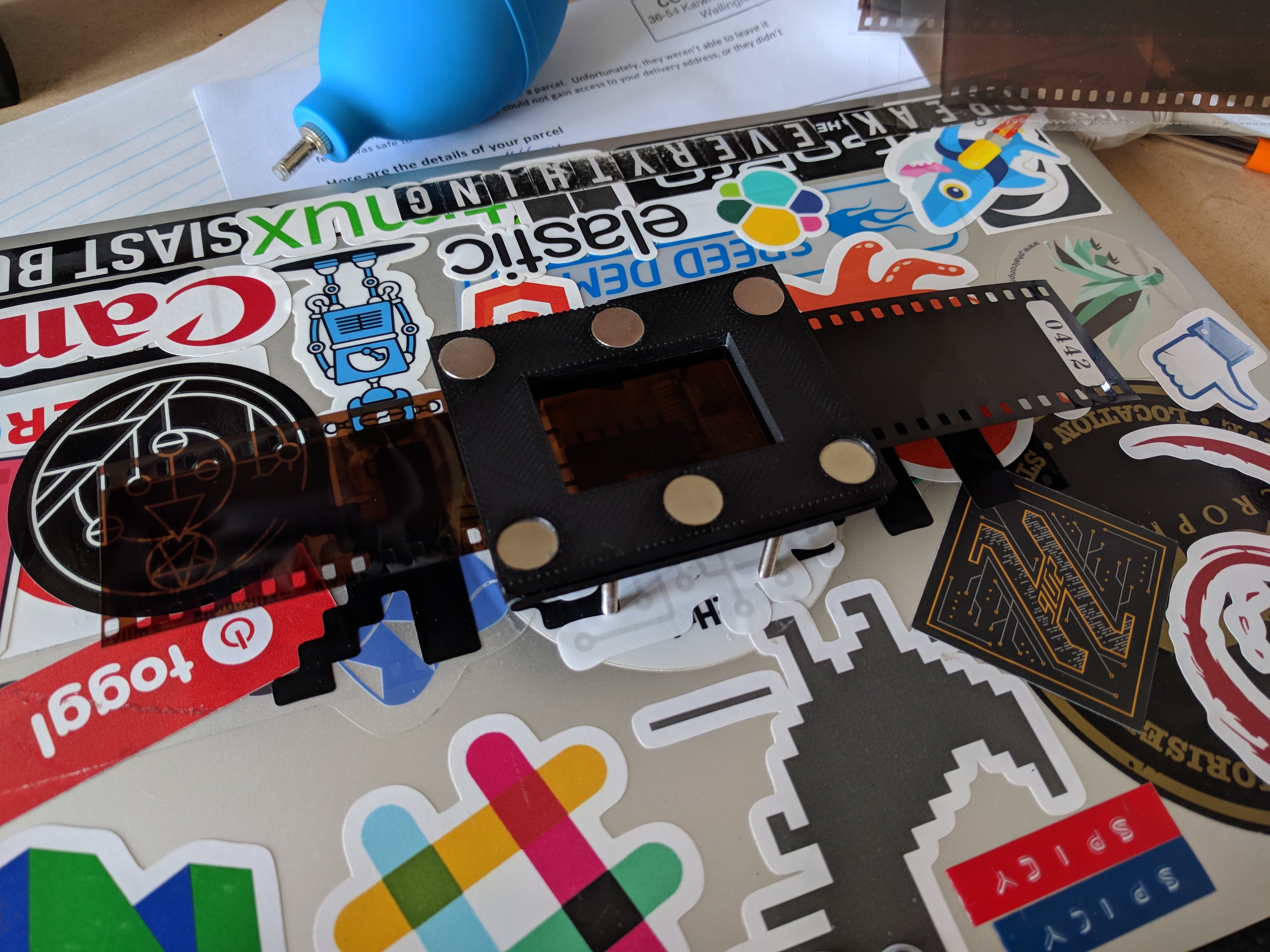

Sketching out where the magnets will fit. The existing design was then adjusted to have a top plate that puts the magnets in each half as close together as possible. Screw holes were added to attach the mount to a yet unknown light source, and enough tolerance was given for the film guides to slot into the top plate without catching.

![]()

![]()

![]()

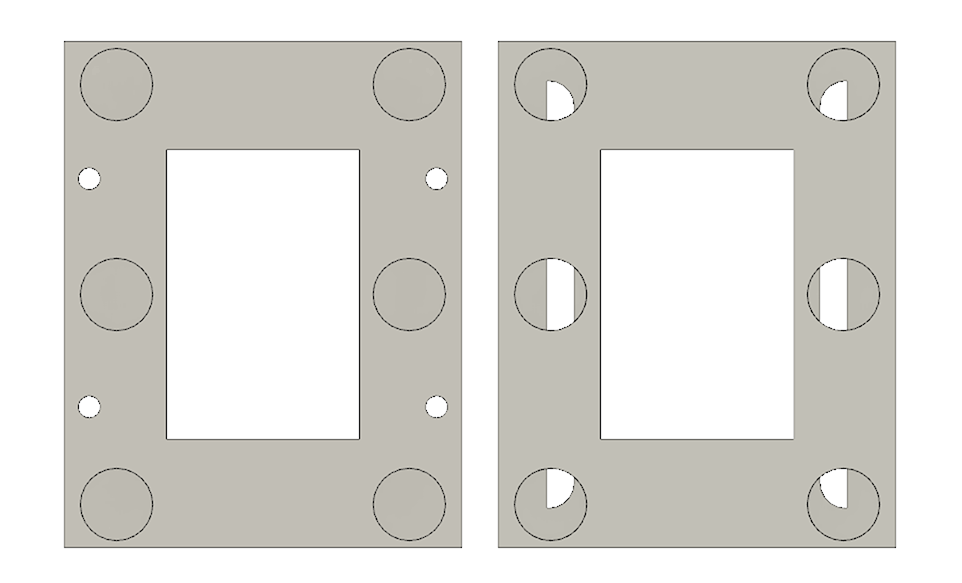

I printed this in ABS, and it worked even better than I was expecting in practice. The magnets provide enough clamping force to flatten out the film, and additionally make the two halves self-align. As long as the top plate is chucked within 1cm of the right place, it homes itself.

![]()

Printed in ABS with magnets inserted in both halves. I used twelve 10mm x 1mm neodymium magnets in each half.

Stephen Holdaway

Stephen Holdaway