Compact, low-power Geiger counter

A marker pen sized Geiger counter with up to 12 months battery life from 2xLR44, based on STM8L152K4 microcontroller

A marker pen sized Geiger counter with up to 12 months battery life from 2xLR44, based on STM8L152K4 microcontroller

To make the experience fit your profile, pick a username and tell us what interests you.

We found and based on your interests.

geiger_pen.zipSchematic, PCB files, firmware in assemblyx-zip-compressed - 228.88 kB - 03/20/2023 at 16:46 |

|

|

c-source.zipx-zip-compressed - 7.38 kB - 01/27/2023 at 19:04 |

|

|

schematic.pdfAdobe Portable Document Format - 83.05 kB - 01/27/2023 at 19:04 |

|

|

Even though the old booster is more efficient than those in most dosimeters on the market, it can be improved further. In fact, initially I chose the least elegant approach, just taking a conventional booster design and reducing its quiescent current through the use of low-power components and high-value resistors, but I made no architectural enhancements to it. The compact inductor I used wasn’t good for efficiency either. I was certain that there had to be a way to significantly lower the booster’s power consumption, yet I lacked any viable ideas.

Later I realized that the correct solution was to take the feedback from the transformer’s primary winding — the same principle as in photoflash chargers like LT3484. The main benefit of that method is that it doesn’t waste energy on the feedback at all as there is no divider at the output to drain the capacitor. The 1:12 transformer enables the use of transistors rated for lower voltages, as they have better characteristics than the high-voltage ones. Two ultrafast 1000V diodes and a 100nF 630V polypropylene film capacitor are used to minimize the HV leakage.

I also decided to use a different battery because LR44 batteries cannot deliver enough current for the new booster to work efficiently. Furthermore, with a larger battery and the more efficient booster there’s an opportunity to prolong the dosimeter’s single-charge lifespan for more (maybe a whole lot more, see below) than half a dozen years, eliminating the need for battery replacement entirely. I really wanted to use a battery with low self-discharge but they turned out to be unsuitable: Li-SOCl₂ batteries are dangerous and produce too much voltage to safely drive the LCD, Li-CFx batteries have too high ESR which increases even more at low temperatures. I went with a CR1/2AA 950 mAh Li-MnO₂ battery, as it can easily deliver sufficient current to the booster at a price of having higher self-discharge than the other two options, but not by much. With all those improvements the new booster consumes 0.56 µA at a normal background radiation level, quite a step up from 8.6 µA in the prior design.

In retrospect, the solution to the problem of designing an efficient booster was right in front of me from the very beginning. While doing initial research I saw many articles mentioning the voltage waveform on the inductor; it’s a short pulse (VLXI) that begins when the transistor is closed, its amplitude equal to the output voltage if a regular inductor is used. If a transformer or an autotransformer is used, the pulse amplitude is divided by the transformer turns ratio (1:12 in our case).

The idea is to keep switching the transistor until the VLXI (kickback pulse of the primary) reaches roughly 400V / 12 = 33.3V. A 30V Zener is used to signal the microcontroller to turn off the booster when the VLXI had reached the desired voltage. I'm not sure why a 30V and not 33V Zener works, something is probably suppressing the peak of the kickback pulse but with a 30V Zener the booster stops when the output reaches 405V.

What’s left is to estimate when the dropping voltage in the output capacitor reaches a threshold value and then schedule a booster restart at the predicted moment. With this approach the output voltage is bound to fluctuate quite significantly because there is no way of knowing when exactly to recharge the capacitor since the voltage at the output cannot be measured without turning the booster on. Thankfully there is no need to keep the Geiger tube voltage at exactly 400V, since its minimum operating voltage is 380V, so just keeping it above 380V should be good enough.

The rest of the circuit revolves around the transformer, so it’s gonna be the main focus of this post. I decided to use the RM5/I 3C90 gapless ferrite core because it’s the largest core...

Read more »I am finally able to post the firmware, it has been rewritten in full assembly by @hidefromkgb and executes from RAM. As I expected, the device now consumes around 17-18 uA which means around 11 months of battery life, maybe even 12, since the previous firmware version lasted for 5 months instead of expected 4 months. However, I'm starting to have bigger plans for it. I realized that there is a lot of unused flash memory that can be used to log radioactivity data and display it via PC interface. Also check the drawing of a custom LCD that the final version may get:

There also will be a major update to the HV booster to get as much efficiency as possible with this form factor but it requires a custom transformer, and it will take some time to design and make. Two years of battery life is the new goal!

It's been 4 months and this thing is still running fine. The battery voltage is 2.2V, so I'm expecting it to run for another month or two. Also the code has been rewritten in assembly and now executes from RAM, though it still needs some polishing, I'll post the details in the next update. Disabling flash reduced the consumption by 25 uA and now the entire device consumes 19 uA, which means 11 months of battery life. I've also managed to find some better parts which should reduce the PCB size and power consumption even further. My current goal is 1 year of non-stop operation.

There are only two things left to implement — LCD display functions and basic control functionality: sound switch, backlight, buttons for switching display mode and resetting the dose. I don't see much point in explaining how it works, let's get to the results instead. The total current consumption when counter is idling is 44 µA, which is low enough to avoid the battery capacitance derating. Given that the speaker is disabled, and battery capacitance is 150 mAh (the device stops working at 1.8V, so we can have individual cells discharged to 0.9V, utilizing their full capacity), this gives us a total working time of 3409 hours or 142 days or 4.7 months. This is a best-case number, so I've rounded it up to 4 months. I've left the device turned-on and will post the actual number of days it managed to last. At the moment of writing this, it has been working for 12 days non-stop without any problem and the battery loses around 8mV per day.

I'm happy with the code performance too. The whole update routine (radiation rate, dose calculations, time update and LCD print function) takes only 16 ms or 524 clock cycles. We save some power because the CPU spends so little time in the active mode. A friend of mine decided to rewrite the firmware in full assembly, optimizing it even further. I will post an update if he will actually do it.

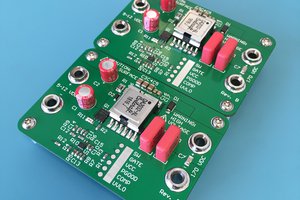

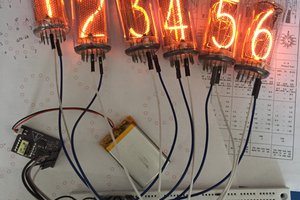

Here's some photos and a video of a finished device. It was designed with an enclosure in mind but apparently, I won't be able to make it any time soon.

Source code and schematics are available on my Github.

To save power, I've decided to update the display once in 5 seconds. Dose rate is a statistical value, so there's not much point to update it faster. Between updates we can stop the CPU, since the boost converter and the radiation event counter work independently of it. We have one last timer to spare, and we're going to use it to generate CPU wakeup interrupts every 5 seconds. After wakeup, we'll update the dose rate and total dose values and put the CPU back to sleep until the next interrupt. First, we should set up the timer:

/* TIM4 SETUP (5-SEC INTERRUPTS) */

CLK_PCKENR1_bit.PCKEN12 = 1; // Enable TIM4 clock

TIM4_PSCR_bit.PSC = 0xE; // Div by 16384 -> 0.5 sec resolution

TIM4_ARR = 9; // 5-second period (sec = + 1) / 2)

TIM4_EGR_bit.UG = 1; // Update timer registers to apply prescaler value

TIM4_CR1_bit.CEN = 1; // Start the timer

TIM4_IER_bit.UIE = 1; // Enable TIM4_UIF interrupt (timer overflow)

WFE_CR3_bit.TIM4_EV = 1; // TIM4 interrupts can wake the CPU from Wait mode

And then we just call the update function when the CPU is woken up by interrupt from TIM4 and then put it back into Wait mode after the function is executed:

int main(void)

{

...

FLASH_CR1_bit.WAITM = 1; // Disable Flash memory during Wait mode

while(1)

{

if (TIM4_SR1_bit.UIF == 1) {

TIM4_SR1_bit.UIF = 0; // Reset interrupt flag

app_readGeiger();

}

asm("WFE"); // Enter Wait mode

}

}

Notice that this happens in the main loop, there is no interrupt handler. Since there's nothing time-critical happening here, we don't need them, we'll just waste precious CPU cycles to enter and exit an interrupt.

The challenge with reading the value from the timer is that the event may occur during reading process, causing rollover or missed readings. Also, we should apply dead-time correction to the value we've read because at high counting rates, a Geiger tube may not have enough time to recover to register pulses occurring at quick succession, which leads to reduced measured activity. The equation for the dead-time correction is:

where N — true counting rate (in events per second), n — measured counting rate, Td — dead time of the tube. This equation is meant for 1-sec measurement intervals, and we're measuring with 5-sec intervals. This will reduce the dead-time effect by 5. The dead time of SBM-20 tube is 190µS, so the effective dead time will be 190/5 = 38µS:

This equation involves floating-point numbers and will be too challenging to calculate for an 8-bit microcontroller, running at 32.768 kHz. We can simplify it with a polynomial approximation:

The deviation increases with n, and at 1400 CPS the approximation gives a value, that's 1.15% higher than the original equation gives. Not too much accuracy to lose, given a massive performance gain that we get from this approximation, isn't it? Let's write the code. Since we need to read and clear the timer as fast as possible, I'll use assembly to do this. And while I'm at it, I'll do the dead time correction in assembly as well. You can check the STM8 programming reference (PM0044) if something isn't clear.

uint16_t cp5s; // Registered events during 5-sec interval

void app_readGeiger(void)

{

// Read and clear TIM3 counter

// TIM3_CNTRH must be read first to prevent rollover

asm("LD A, TIM3_CNTRH");

asm("CLR TIM3_CNTRH");

asm("PUSH TIM3_CNTRL");

asm("CLR TIM3_CNTRL");

asm("PUSH A");

asm("LDW X, (0x01, SP)"); // now both stack and register X hold cp5s value

// Apply dead time correction: cp5s...

Read more »

There are two ways to read the signal — from the anode and from the cathode of the tube:

I'll be reading signals from the anode because it's more convenient to route the PCB this way and this approach provides more immunity to electrical noise. In case of anode readout, the main goal is to reduce the pulse amplitude, so it doesn't destroy the MCU. The schematic is as follows:

C1 and C2 act as a capacitive divider, attenuating pulse amplitude. C1 must be rated for more than 400V, I'm using a 2kV rated one. R1 is just a pull-up resistor: because the pulse is negative going, the idle voltage level should be high. I am deliberately not using MCU's internal pull-up resistor here because its value is too low, and it will shorten the pulse too much because of that. The diodes are used to clip the pulse amplitude to a safe level. Let's see how the output pulse will look like when a Geiger tube registers a radiation event:

The output pulse swings from supply to ground with some overshoot due to voltage drop in diodes. High amplitude of the pulse allows us to use a digital input to register it.

I would like to be able to hear when a radiation event is registered, and I want it loud. There are two types of sound transducers — magnetic and piezoelectric. Magnetic ones require high current, so they're out of the question, also they're not that loud compared to piezoelectric. The problem with piezoelectric transducers is that they require high voltage to produce a loud sound, so we need the means to generate high voltage pulses. Here's what I came up with:

This circuit works similar to a boost converter. When the transistor is open, the inductor starts building up current and the remaining charge in the transducer is removed to increase voltage swing across it (electrically they behave like capacitors, so they can hold some charge). When the transistor closes, the energy that the inductor had at that time, is transferred into transducer's capacitance and it stays there until the next cycle. I've created a simulation if you want to take a closer look at the circuit's operation.

I'm using a KPT-G1210 transducer, it's rated for 30V, so let's generate voltage somewhere in this vicinity. As I said before, the energy EL held by an inductor is transferred into transducer's capacitance:

where:

From the formula above we get:

where

In this case, Ra is the sum of inductor's series resistance and MOSFET's drain-source resistance. We can control two parameters in this circuit — the inductor value and its charging time tON. I've selected a 33mH inductor to reduce its peak current; LR44 battery has high ESR, so if we pull too much current from it, we may get brownouts at low battery levels. This leaves us only with the tON to figure.

We'll be using a TIM2 timer in the MCU to generate pulses. It has a one-shot mode and an external trigger, so we'll set it to produce a single pulse of fixed length when its trigger input TIM2_ETR detects a falling edge from the Geiger tube. I've added this code to the TIM_Init() function:

/* TIM2 SETUP (ONE-PULSE MODE, EXT. TRIGGER) */

PB_DDR_bit.DDR2 = 1; // Set PB2 as output (TIM2_CH2)

PB_CR1_bit.C12 = 1; // Set PB2 as push-pull

CLK_PCKENR1_bit.PCKEN10 = 1; // Enable TIM2 clock

TIM2_ARRH = 0;

TIM2_ARRL = 6; // Pulse length = 30.52uS * TIM2_ARRL

TIM2_CCR2H = 0;

TIM2_CCR2L = 1;

TIM2_CCMR2_bit.OC2M = 7; // PWM mode 2

TIM2_CR1_bit.OPM = 1; // One-pulse mode

TIM2_SMCR_bit.TS = 7; // Trigger source - external

TIM2_ETR_bit.ETP = 1; // Trigger on falling edge

TIM2_SMCR_bit.SMS = 6; //...

Read more »

Most DIY Geiger counters that I've seen on the Internet have very simple architecture: just an oscillator driving a transistor, sometimes with Zener diodes to limit the output voltage. This approach is inefficient, so I've decided to make a boost converter that's both efficient and compact. The first thing that comes to mind is that the converter has to disable the oscillator when it's not needed. This approach is described in an appnote by Maxim Integrated:

Here they're using a comparator to control the oscillator output: when the feedback voltage is less than the reference voltage the oscillator is enabled, and vice versa. Since a Geiger tube only consumes energy when hit by a particle, the oscillator shall remain idle most of the time, and that saves a lot of power. Also there's a 6-stage voltage multiplier, so we can feed the lower output voltage from its first stage to a feedback divider, thus minimizing the current through it. I'll be reducing losses in the feedback divider as much as possible since it consumes the most power in the circuit above.

One huge benefit of microcontrollers is that they have peripherals that can replace discrete components, saving power and PCB space. In our case we can use a microcontroller to replace a voltage reference and an oscillator in the circuit above (and even a comparator if we wouldn't have to drive a 4-backplane LCD).

We should set the MCU to output a reference voltage and a comparator-controlled PWM: when the comparator output is LOW (voltage divider voltage less than reference voltage), the timer generates PWM, otherwise it sets its output to LOW, closing the transistor. The only timer that we can use is TIM1 because pins, tied to other timers are needed for other functions. This timer has a break input which disables timer's output when it receives a signal, which is exactly what we need. The schematic is as follows:

To use a lower value inductor for better energy and space efficiency, we'll set the PWM generation for shortest positive pulse possible, i.e. highest frequency and lowest duty cycle; the best we can get with a timer is half the system clock. The MCU is clocked from 32.768 kHz crystal, which means 50% duty cycle PWM at 16.384 kHz.

To write the code I'll be using the IAR Embedded Workbench for STM8.

#include "iostm8l152k4.h"

void Clock_Init(void)

{

CLK_SWCR_bit.SWEN = 1; // Prepare to change the clock source

CLK_SWR = 0x08; // Change the clock source to LSE

while(CLK_SWCR_bit.SWBSY==1); // Wait until it starts up

CLK_CKDIVR = 0x00; // Change the clock prescaler from default /8 to /1

CLK_ICKCR_bit.HSION = 0;

CLK_ICKCR_bit.LSION = 0; // Disable internal oscillators

}

void VREF_Init(void)

{

while(!PWR_CSR2_bit.VREFINTF); // Wait for voltage reference to stabilize

CLK_PCKENR2_bit.PCKEN25 = 1; // Enable clock for COMP peripheral

COMP_CSR5_bit.VREFTRIG = 2; // Disable Schmitt trigger on PD7 to reduce leakage

COMP_CSR3_bit.VREFOUTEN = 1; // Enable VREF output

RI_IOSR2_bit.CH8E = 1; // Connect VREFOUT to PD7

CLK_PCKENR2_bit.PCKEN25 = 0; // Disable clock for COMP, was only needed for init

}

void TIM_Init(void)

{

/* TIM1 SETUP (SYSCLK/2 GATED BY EXTERNAL SIGNAL) */

PD_DDR_bit.DDR4 = 1; // Set PD4 to output mode

PD_CR1_bit.C14 = 1; // Set PD4 output to push-pull mode

CLK_PCKENR2_bit.PCKEN21 = 1; // Enable TIM1 clock

TIM1_ARRH = 0;

TIM1_ARRL = 1; // Highest frequency (16.384 kHz)

TIM1_CCR2H = 0;

TIM1_CCR2L = 1; // Lowest duty cycle (50%)

TIM1_BKR_bit.BKE = 1; // Enable output break

TIM1_CCMR2_bit.OC2M = 0x6; // Set output mode: PWM mode 1

TIM1_CR1_bit.CEN = 1; // Enable timer counter

TIM1_CCER1_bit.CC2E = 1; // Enable TIM1_CH2 output

TIM1_BKR_bit.AOE = 1; // Automatically recover from output break

}

int main(void)

{

Clock_Init();

VREF_Init();

TIM_Init();

}

The beauty of this approach is that it's completely...

Read more »

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.

Very cool project. Nicely done!

How to set the value of RP1?

Thanks! Sorry for late reply.

First set RP1 to the maximum position, it should have ~1M resistance. Then switch the power on and measure the voltage at the point where D4 and C14 meet. Adjust RP1 until the multimeter shows 100V. I also assume that your multimeter has ≥10MΩ input resistance, I haven't tested how the booster behaves with higher loads.

Hey, I really like this project. with the logs saved on the eeprom, how are you able to access it later on? I was looking to have a device like this to log my radiation exposure, how would I see the monthly stats or even yearly? only through the LCD?

Logs are not implemented in this version but the next version will save logs to internal flash and it'll be possible to access them via USB interface.

Hi. Its really good project. Trying to assembly by myself. Can you help me with some guide how to compile the firmware? I mean which tool I need to use to build hex file and upload. Thanks in advance.

I was using IAR Embedded Workbench for STM8, free version with code size limit. Just open the .eww file and upload the project via ST-Link.

[this comment has been deleted]

Currently I'm planning to sell this as a finished product, with an enclosure and stuff but it's hard for me to plan very far ahead, so kits are possible too (though unlikely). If everything fails, I'll ditch the idea with custom LCD and transformer and just sell the PCB with off-shelf parts like the posted dosimeter uses.

I am interested too. Very cool project. I never seen such a measurement tool in such a small form factor ! Well done.

No, but it outputs registered radiation events (MCU pin 15), so you can connect it to another device with radioactive@home functionality

Nicely done! Clean construction and very unique; not many projects on this site use ST8 and bare LCD displays.

congrats on the 11 months, I think you will make the 1 year goal. wondering how to get a ready made PCB and possibility of making more than 1. although I understand all the motivation is in the engineering phase. sitting on the fence to join the project.

Sorry but the posted prototype was never intended for factory production, I prefer to etch PCBs at home. I've attached some PCB files to the project, you can try adapting it for your needs.

living here in Tokyo and having driven thru Fukushima 2 years ago, I find a definite NEED for one of these. Wondering if a RP2040 in deep sleep mode could save any more power?

If you get a sample 10 piece run of your next PCB I would love to assemble a prototype and give you feedback on operation.

Hi. I already see there's enough people interested in getting one of these counters, so if I won't run into any major problems, I'll definitely make a small batch. There's also an enclosure to be made for it and I haven't worked on it so far...

RP2040 is, from my experience, a very poor choice for low-power applications, it has very high standby current and its low-power modes are not very feature rich.

Great project. I am interested in making one. Would you be willing to share the schematic in and importable format (EasyEDA, Eagle...)?

I can share the schematic when I'll have access to my home PC (around a week). Also In the next update I will release the updated schematic and board files, most likely in EasyEDA format, you can wait for that as well.

Sorry for the late update. I've attached EasyEDA schematics to the project zip file.

4 months or the rest of your life…depending on the amount of radiation.

Become a member to follow this project and never miss any updates

Radu Motisan

Radu Motisan

James Wilson

James Wilson

Paul Andrews

Paul Andrews

Caleb W.

Caleb W.

Congrats for the super impressive project! I love your detailed logs -- so much so that I shamelessly stole your previous boost design for half of my SiPM bias generator. Thanks!