-

Software

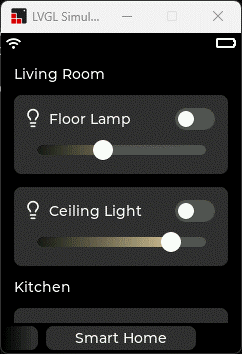

07/01/2023 at 08:46 • 0 commentsOne of the reasons for starting this project was that I wanted to try out LVGL. LVGL is an open-source embedded graphics library that is well optimized to run on microcontrollers like the ESP32. You can create user interfaces using a set of building blocks like buttons and sliders and add styles and animations to them. With little effort these UIs end up looking beautiful and professional. There is even a drag and drop editor, Squareline Studio, that generates the necessary code for you. To be more flexible, I decided to start with the LVGL simulator for Visual Studio.

For my universal remote interface, I am using multiple pages, that can be scrolled through by swiping horizontally. Each device has its own page that contains the corresponding buttons. There is a larger settings page, that can also be scrolled vertically. These pages are set up as a “tabview” object so they behave like a smartphone home screen. Everything about the scrolling and animations is then handled by LVGL. I also added a little page index to the bottom that contains the pages title. These text boxes fade out to the sides using transparent bitmaps, as a reference to the iOS camera app.

![]()

After building and testing the interface on my PC, I copied the code over to Platformio for the ESP32. The touch buttons can then be mapped to sending infrared signals using event callback functions. Display output and touchscreen input is connected to LVGL using the TFT_eSPI and Adafruit FT6206 libraries.

The interface looks nice and sharp even on the 320 by 240 pixel display. UI elements like sliders were working fine immediately at around 30 fps. Only when scrolling the pages, I experienced drops in framerate (9-10 fps) and visible lag at first. Luckily LVGL and TFT_eSPI support DMA and double buffering, meaning that the ESP32 can draw one frame, while the other is sent to the display simultaneously. This takes up more RAM, but it increased the frame rate during scrolling to nearly 20 fps. SPI frequency has a huge impact as well. On paper, the ILI9341 display driver only support SPI frequencies of around 6MHz, but it usually works even at 80MHz. I have had displays that would only work at up to 40Mhz, which leads to a slightly lower performance.

![]()

For many of the additional hardware features, I am using Arduino libraries. “IRremoteESP8266” deals with the infrared sending and receiving. It supports basically any manufacturer’s standard. The LIS3DH accelerometer detects when the device is in motion. I am using Sparkfun’s library to read the acceleration values and to configure the interrupt for waking up the ESP32. Another wakeup source is the tactile button grid. This is handled by the Keypad library which I modified to invert its logic. This way I can use the ESP32’s EXT1 wakeup to detect if the accelerometer pin or any button pin goes high. Booting the ESP32 takes around half a second from the interrupt to the point where the display is turned on.

When the motion detection is used, the display usually turns on before I have a finger on a button.

To make use of the 2.4GHz antenna, I created another UI page for smart devices. This way, the remote can control lightbulbs by communicating with my MQTT server over Wi-Fi.

![]()

Right now, the IR codes and button mapping is hard coded for my personal use. A next step would be making the interface configurable. This could be done on the remote itself by expanding the existing touchscreen UI or on a computer using for example a HTML interface that is hosted by the ESP32.

-

Electronics

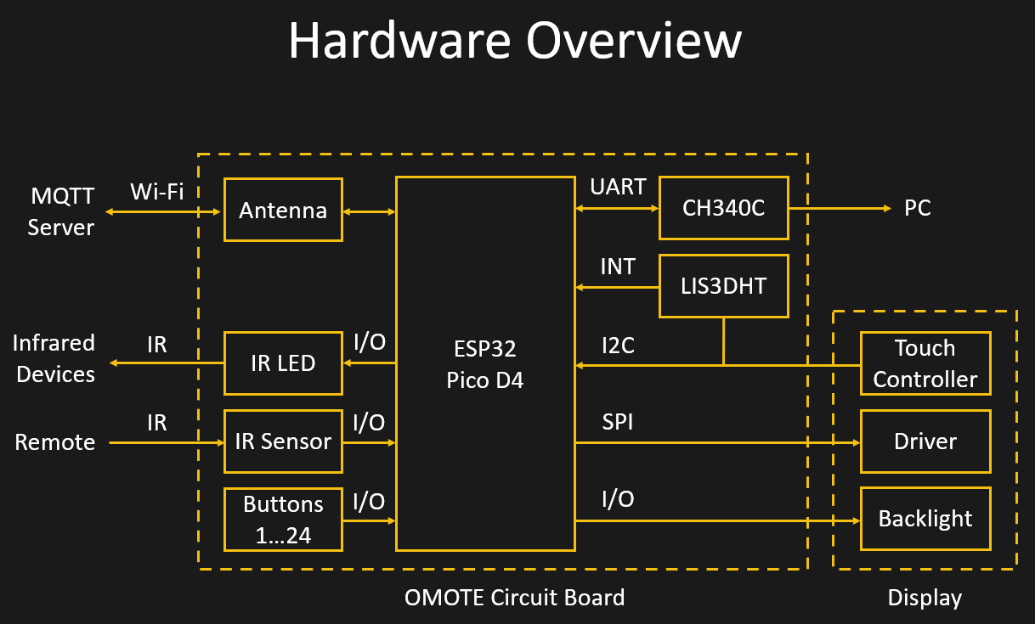

07/01/2023 at 08:43 • 0 comments![]()

Because of its wireless interfaces and low power consumption in sleep mode, the ESP32 is an ideal choice for this project. I included a CH340C serial adapter, so it can be programmed using a USB Type-C port. The same port can also be used for charging a Lithium-Ion battery by including a charging IC.

While the display is powered up and the ESP32 is not in sleep mode, the device quickly drains the battery. To minimize the time in this active mode, a LIS3DH 3-axis accelerometer can detect if the device is moving. Via i2c the ESP32 can check if it stopped moving for a while and power down. An additional interrupt pin wakes the controller as soon as the remote is picked up again.

To save on IO pins, the 24 tactile switches are arranged in a 5x5 grid. Each row is connected to a digital input while the columns are constantly toggled in software. This way, only 10 instead of 24 pins are needed. The five input pins can also be used to wake the device up from sleep. For this, they need to use the same logic (active high) as the accelerometer interrupt and the five outputs must remain High.

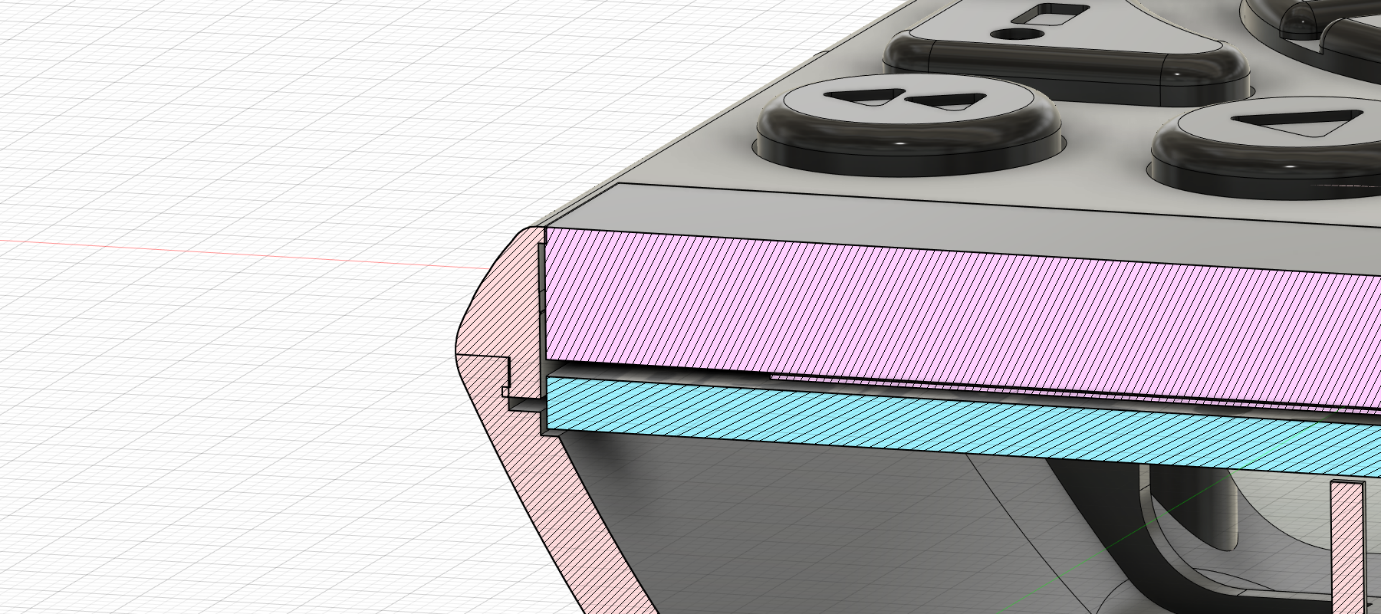

The display is connected to the controller via SPI for the pixel data and i2c for the touchscreen. I am using the ESP32s hardware SPI pins to take advantage of the full 80MHz that the controller supports. The displays backlight can be turned on by a DMG2301 MOSFET. Another one of these MOSFETs is used to switch of the display logic and touch controller since they draw some power as well.

A third MOSFET is used to control the infrared LED. It uses a very small, 3.3 Ohm series resistor to maximize its range. A Vishay TSSP77038 IR Sensor enables it to read and decode commands from other devices.

![]()

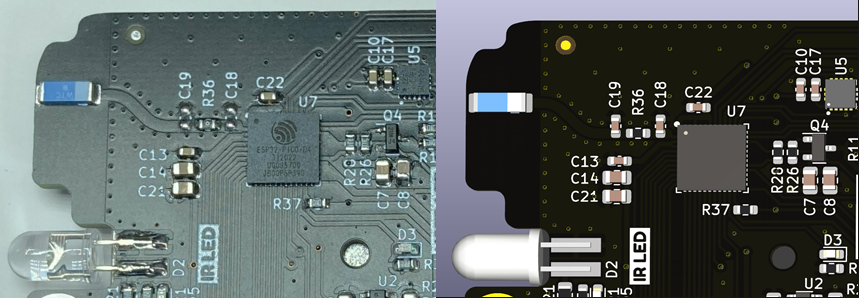

I had already created the basic outline of the PCB in Fusion360, so I simply imported it directly into KiCad. A major challenge was placing the Wi-Fi antenna in such a way, that it is not obstructed by the metal display frame or the hand that holds the remote. The only possible location was the top corner of the PCB, right next to the IR LED. I had used the ESP32-WROOM module previously, but it was too big to fit and half the pins would end up on the edge of the PCB. Instead, I switched to the ESP32-PICO-D4. It’s a 4x4mm System-On-Package that contains most of the components of the WROOM module. An external antenna, like in this case a small chip antenna, can easily be connected to the Pico. Trace antennas would also be an option, but chip antennas usually are more robust against influences like the 3D printed case. The trace line between the ESP32 and the antenna should normally be impedance controlled which is tricky on a 2-layer PCB. I can get away with this by keeping the length below 1/10 of the wavelength (12mm for 2.4GHz). I also ensured that there is a continuous ground layer below the trace line and ESP32 and that vias are placed along the edges.

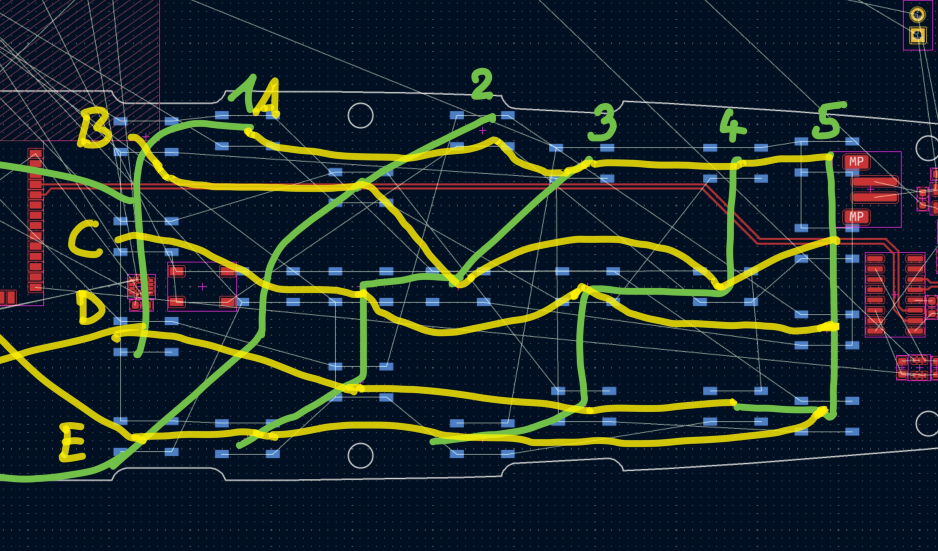

![]()

I am using a regular 5mm infrared LED that is soldered to the top edge of the board. The IR receiver is placed next to it. A 40 Pin connector is used for the display, while its cable goes through a cutout in the PCB. Another cutout makes room for the touch controller that protrudes the display cables. This allows the display to be glued flat on the PCB. On the lower end of the PCB, there is room for the USB Type-C connector, the serial adapter and the charging IC. The only components on the other side of the board are the tactile switches. For the button matrix to work, these switches need to be arranged in a 5x5 grid. It was a little tricky figuring out the placement so the traces don’t cross.

![]()

Since the ESP32-PICO-D4 only has pins on the bottom, it needs to be reflowed. Luckily, I have a small hot plate that I could put to proper use for the first time. Since the hot place is only 3x3cm, I had to move the board around during soldering. For solder paste, I used the MECHANIC XGZ4 and set the plate to around 220°C. As this was my first try at reflow soldering, I was amazed at how clean the solder joints look afterwards.

![]()

With the final software, the board draws around 32uA in sleep mode and 150mA in active mode with the display and ESP32 turned on. Using Wi-Fi adds another 80mA to the active mode consumption. Assuming the remote wakes up one every hour for 10 seconds, the 2000 mAh battery will last around 180 days.

![]()

-

Hardware

07/01/2023 at 08:31 • 0 comments![]()

My initial idea was to build a universal remote with both a touchscreen as well as physical buttons. For communication the remote would need an infrared LED and optionally an RF module for Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. Like in most of my previous projects, I wanted to use common, off-the-shelf components and 3D-printing so anyone can build the remote themselves.

For the display I picked a 2.8” screen from Adafruit with a built-in capacitive touchscreen. Adafruit sells these displays either standalone or on a breakout board. There is also a slightly cheaper version that has a resistive touchscreen. But in my opinion capacitive touch feels nicer for this type of device and the screen is also more durable due to the glass surface.

The size of the screen defines the overall dimensions of the remote. I ended up with roughly 20x5cm.

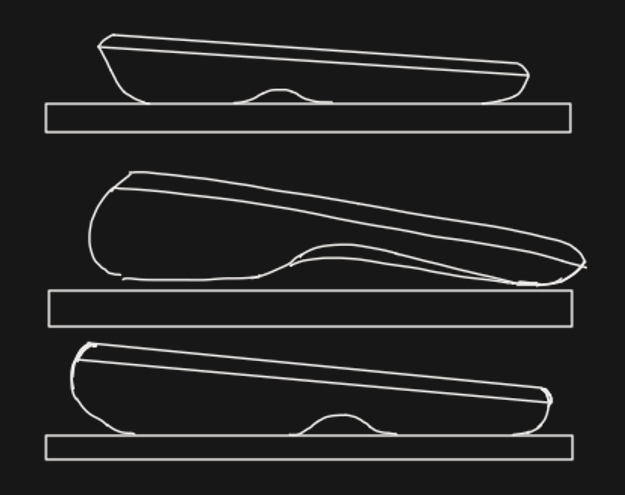

![]()

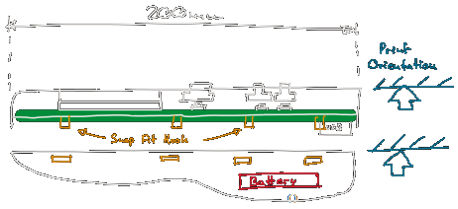

I started by drawing some sketches to figure out the best shape for the remote. To make 3D printing easier, I wanted to keep the top of the remote completely flat. This way the case can be split into two parts. The top part can be printed with the flat outer surface facing the print bed. The larger, lower part will be printed on the separation plane with the inside facing down. This way elements like snap fits can be printed that protrude this separation line.

![]()

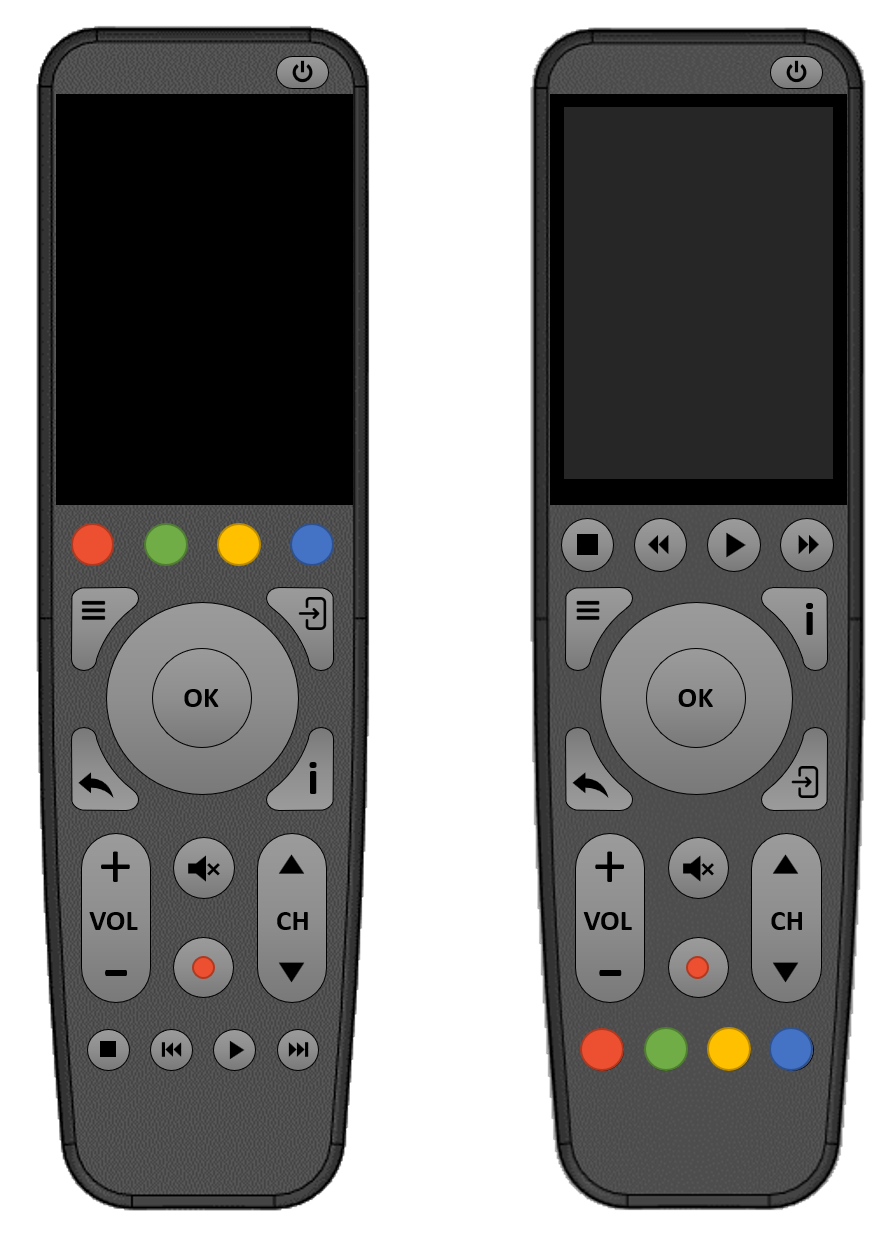

For the buttons I wanted to have the most common media and navigation keys that are needed to control a TV. This includes four-way keys, playback control, four color keys and a few more buttons for functions like input select and menu navigation.

![]()

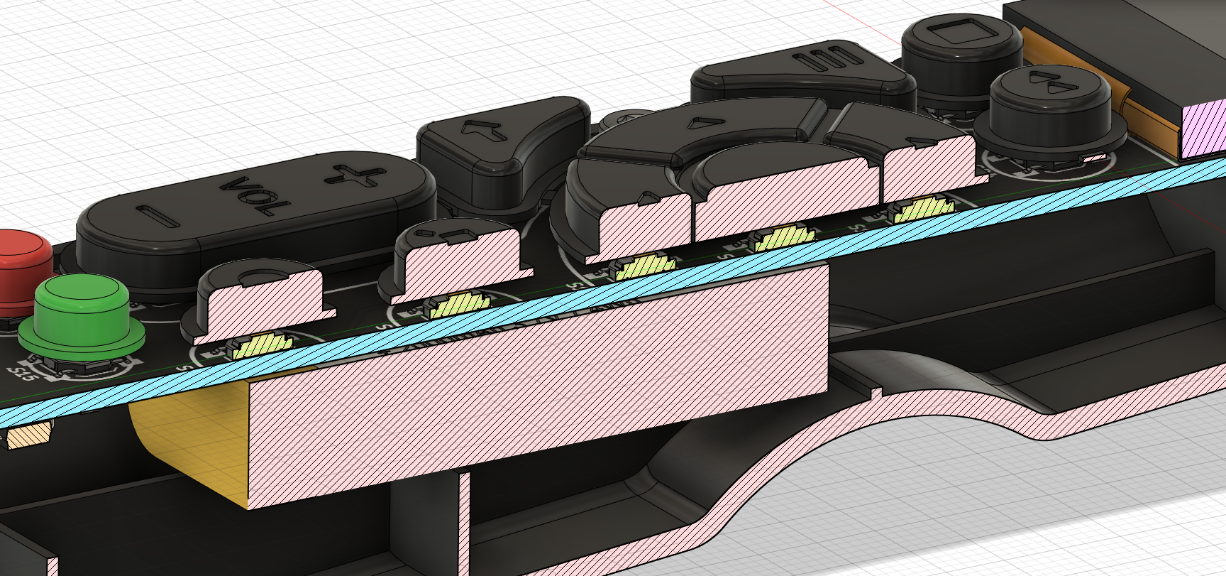

Based on these sketches I went on to create a first concept in Fusion360. It is designed around the large display, so the case is flat and wide at the top. Towards the bottom the remote is tapered and thicker, so it can be held comfortably. A small indent is where the index finger goes, so the thumb automatically lands on the OK button. I printed this first draft to test how the shape looks and feels. Since I happy with it, I barely changed the design but only added more details to it. This included splitting the case into two hollow halves and adding ribs for stability. One of the main challenges was fitting the halves together as I did not want to rely on visible screws. I experimented with small snap fitting hooks but they broke off too easily. Instead, I went with a lip and groove joint that goes around the entire edge of the device. On the sides there is a slight undercut so the parts interlock but can be separated with little force. This obviously means that the 3D printer must be well calibrated or the parts will not fit at all.

![]()

Most commercial remotes use silicone keypads but due to the cost of the required molds, this is impractical for DIY projects. I decided to use regular tactile switches and 3D printed button caps instead. I tried to keep the labels simple, so they could be embossed into the button’s surface. With a 0.4 mm nozzle, these came out fine on my printer.

![]()

For the printed parts, I used matte black PETG filament from ColorFabb and Anthrazit PETG from Dasfilament. I also experimented with a flashier color theme using Colorfabb’s light blue NGEN filament. As the front cover is only snapped into place, it is easily replaceable.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Max.K

Max.K