-

Full Robot Build

10/06/2023 at 14:16 • 0 commentsDesign

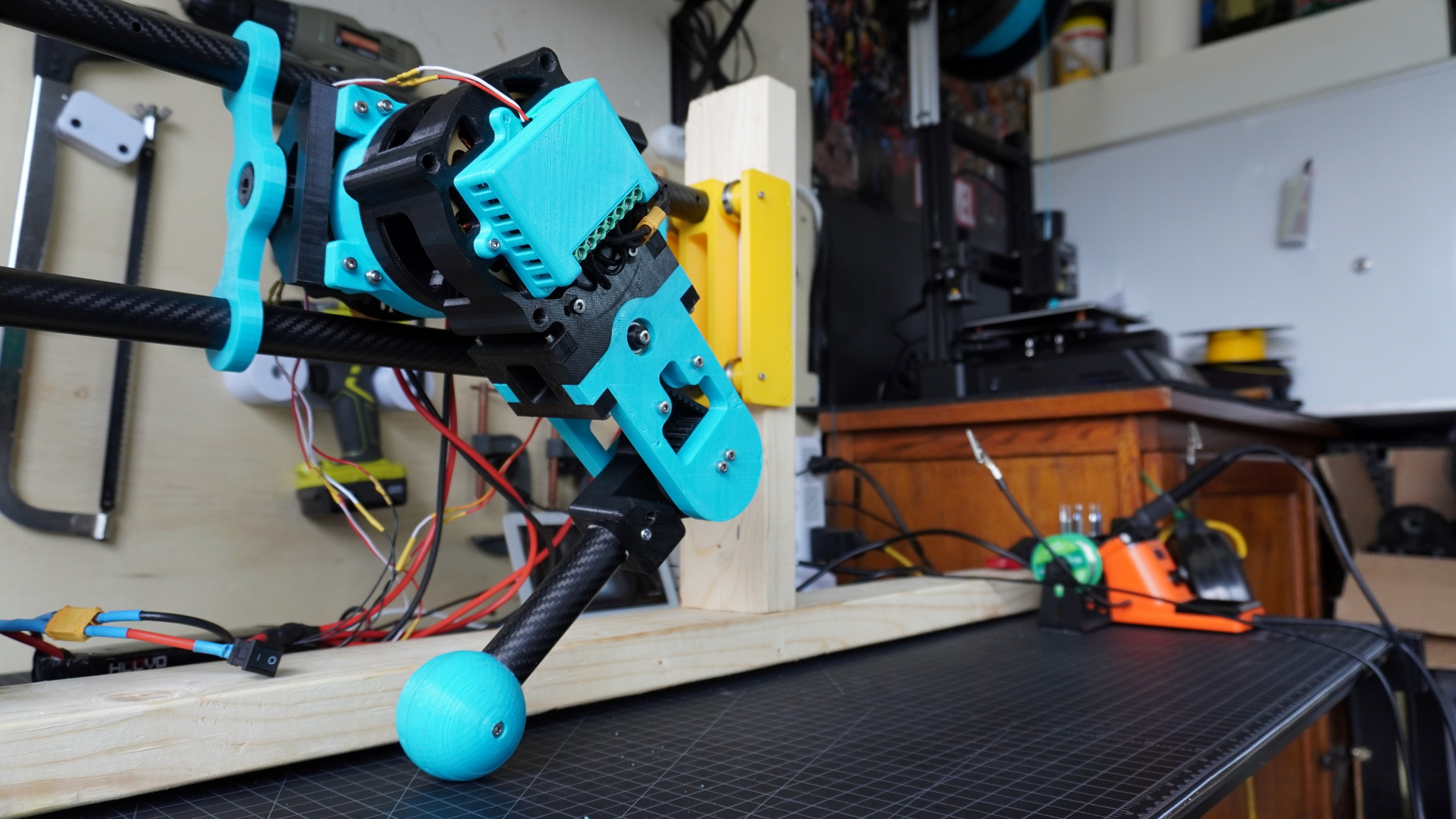

The single-leg design hasn't changed much. I cut off a bit more weight and removed the homing block. This homing block will now be a separate part incorporated into the actual robot design rather than on each leg itself.

The approach that I took to designing the test legs was to have the actuators connect together and make up the main body of the leg. This worked well for a single leg, so I'm applying that same design strategy to the full robot assembly.

The frame of the robot is made up of 4 carbon fiber tubes. Each of the legs slides onto two of the carbon fiber tubes. The front, back, and middle of the robot have panels to hold the 4 tubes in place,

One of my main design considerations was making all of the parts small enough to fit on a 200 x 200 x 200mm print bed.

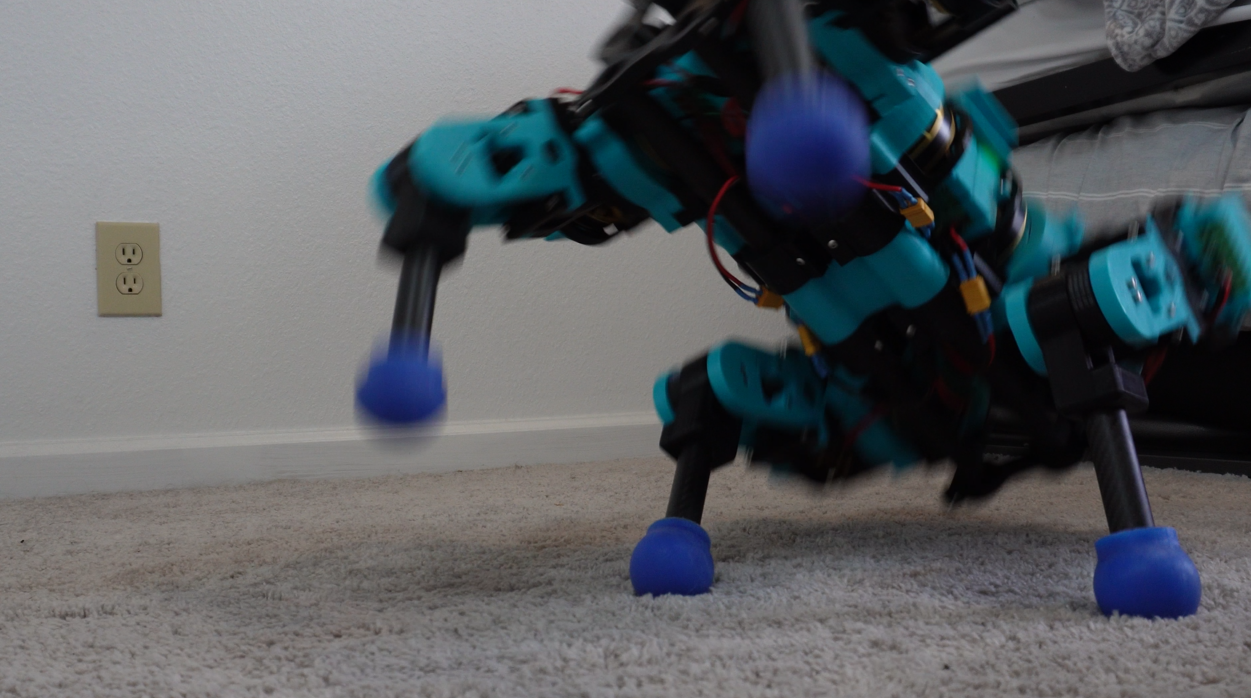

Previously I had just 3D printed the feet on the test legs, but 3D-printed feet have little to no traction. For the full robot, the feet were cast in 30 A silicone which, according to online scales, is somewhere between the squishiness of a rubber band and an eraser. The base of the foot is 3D printed, so the silicone is just applied to the outside of this base. I did this by suspending the part in between two 3D-printed molds and pouring silicone inside.

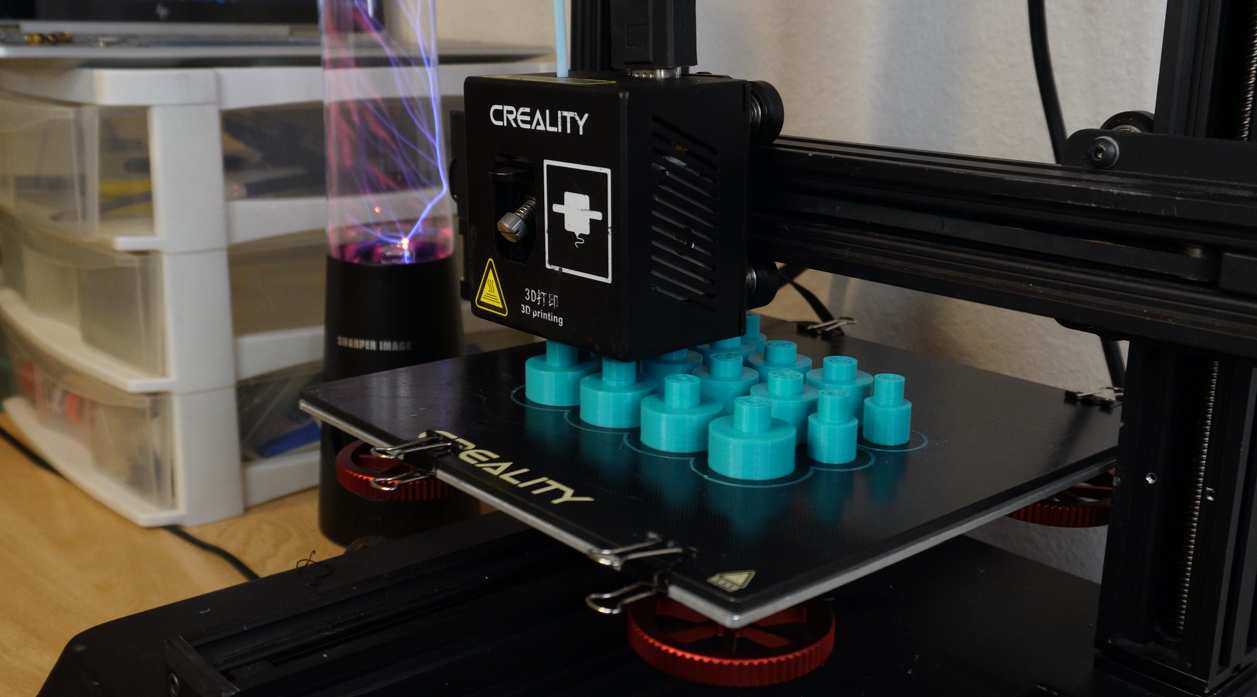

Printing

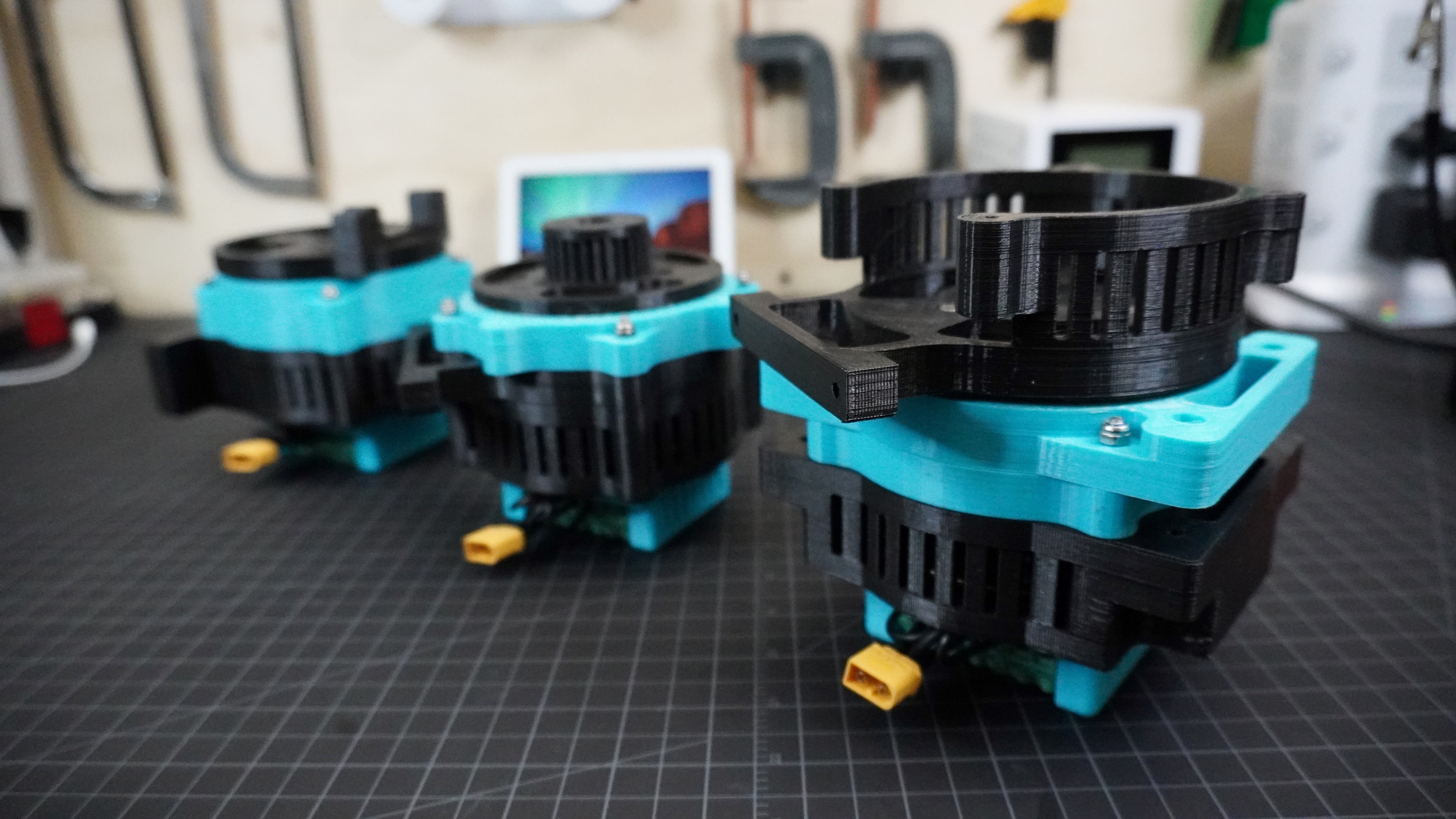

It took about 3 weeks to print all of the parts on my reality CP-01 printer. Overall the 3D printed parts account for 9.98lbs (4.53kg) which is about 1/3 of the robot's weight. I printed all of the parts in black and Bahama blue PLA.

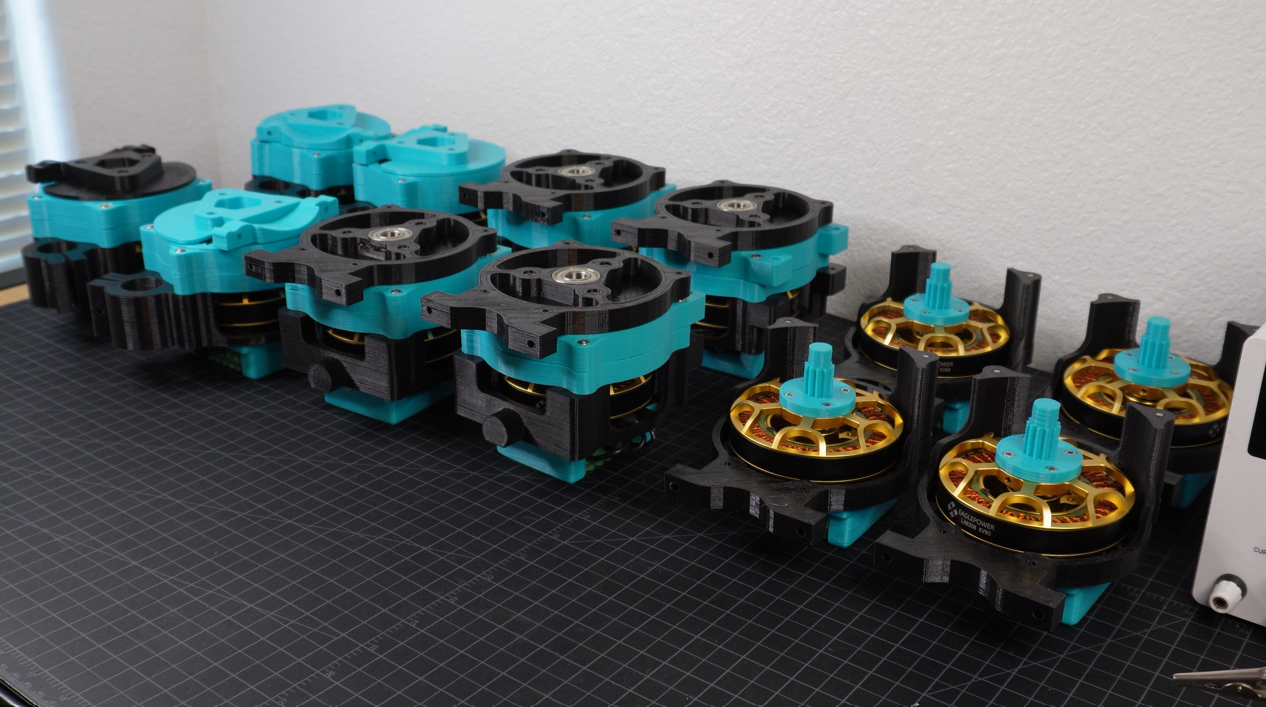

Build

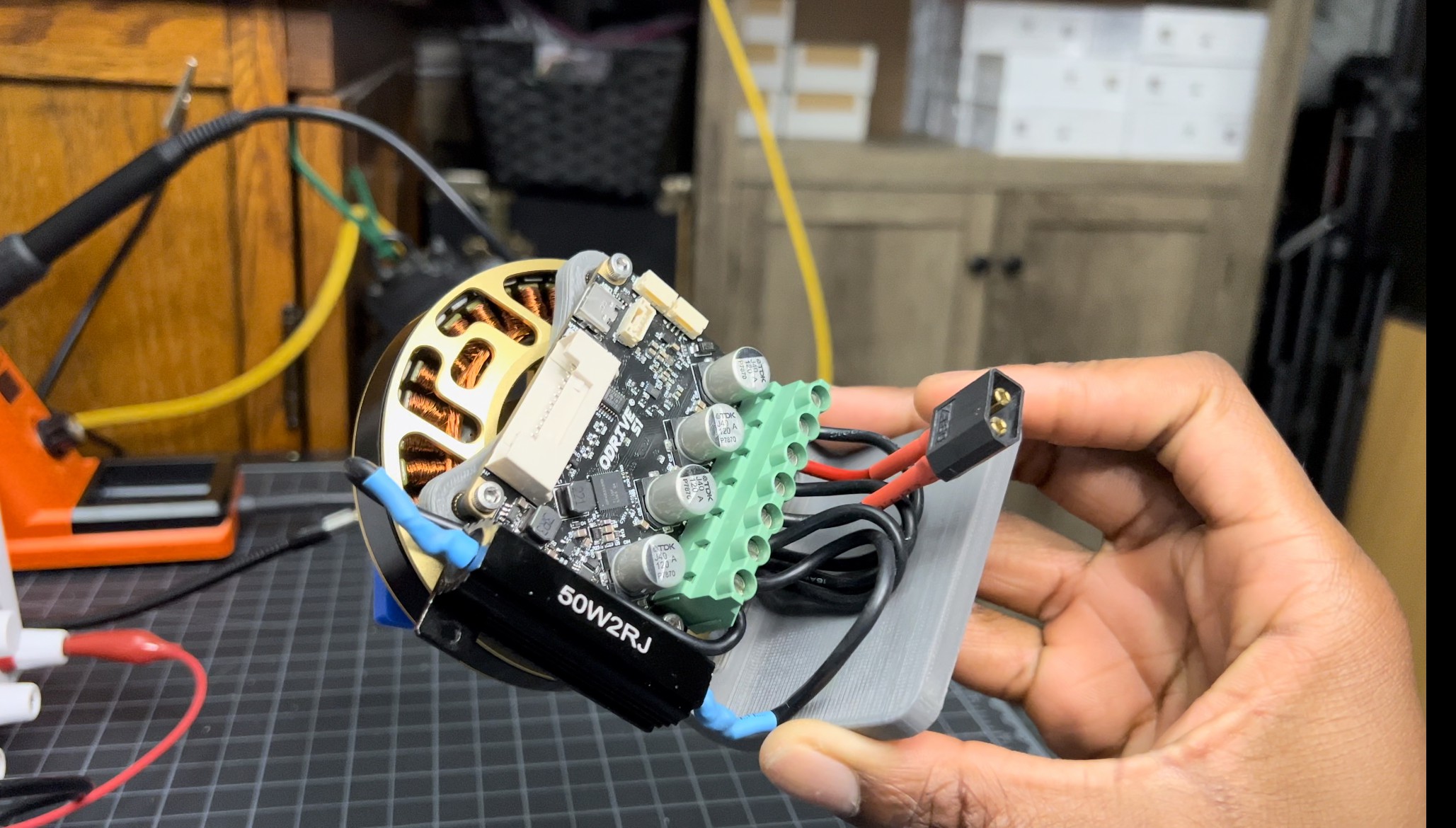

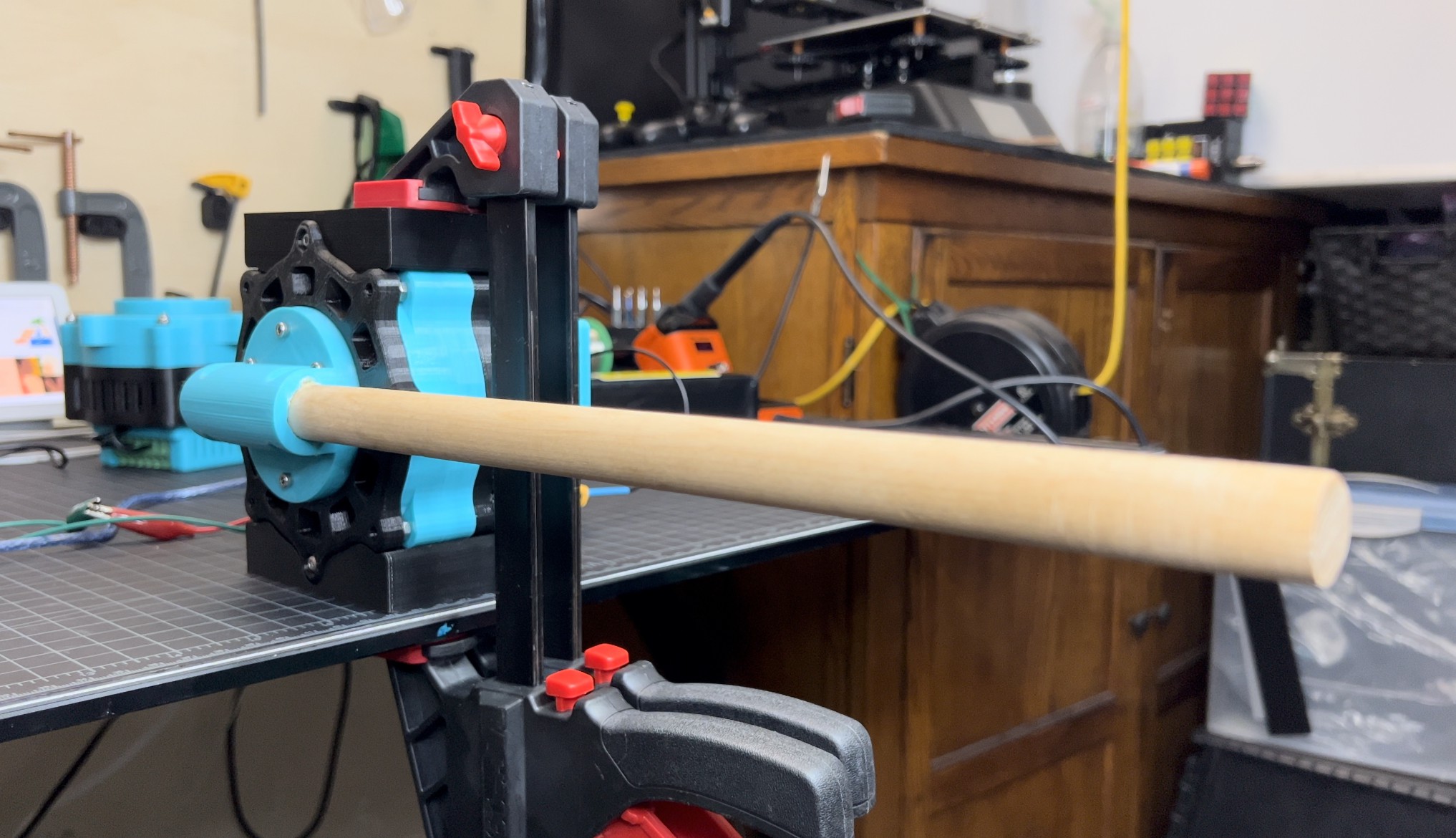

The first step in assembling the robot was to build all 12 actuators using 12x high-torque 90KV brushless motors and 12x ODrive S1 brushless motor controllers with position, velocity, and torque closed-loop control.

To get the actuators up and running, I used the ODrive GUI to change settings, calibrate the motors, and define each actuator's CAN bus node ID.

There are 3 different types of actuators since each leg has 3 types of joints: adduction, hip, and knee. These each fit together to form the body of a single-leg assembly and 4 of these leg assemblies form one 12 DOF robot.

In my single-leg testing, I found that using screws with carbon fiber tubes ended up just making wide and unusable holes. To fix this, I integrated clamps into the design of each adduction actuator’s housing so that I could use a screw to clasp the actuator onto the carbon fiber tube.

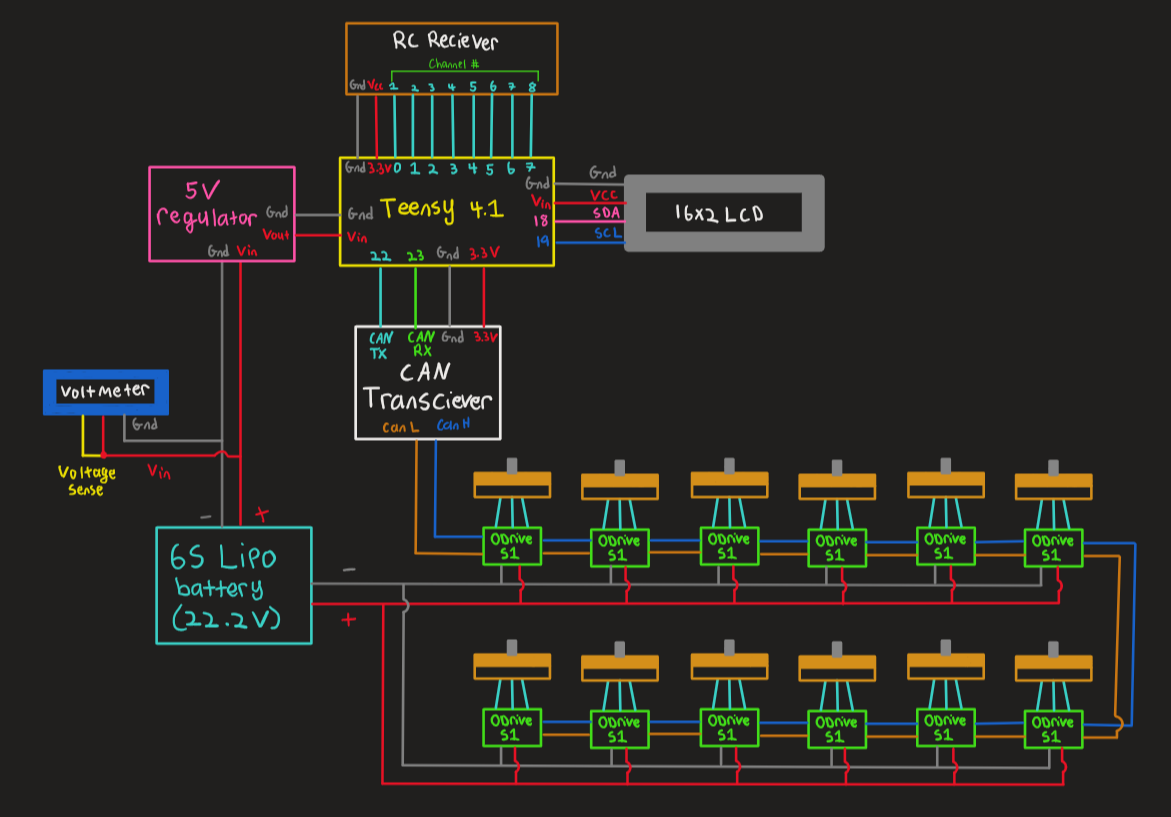

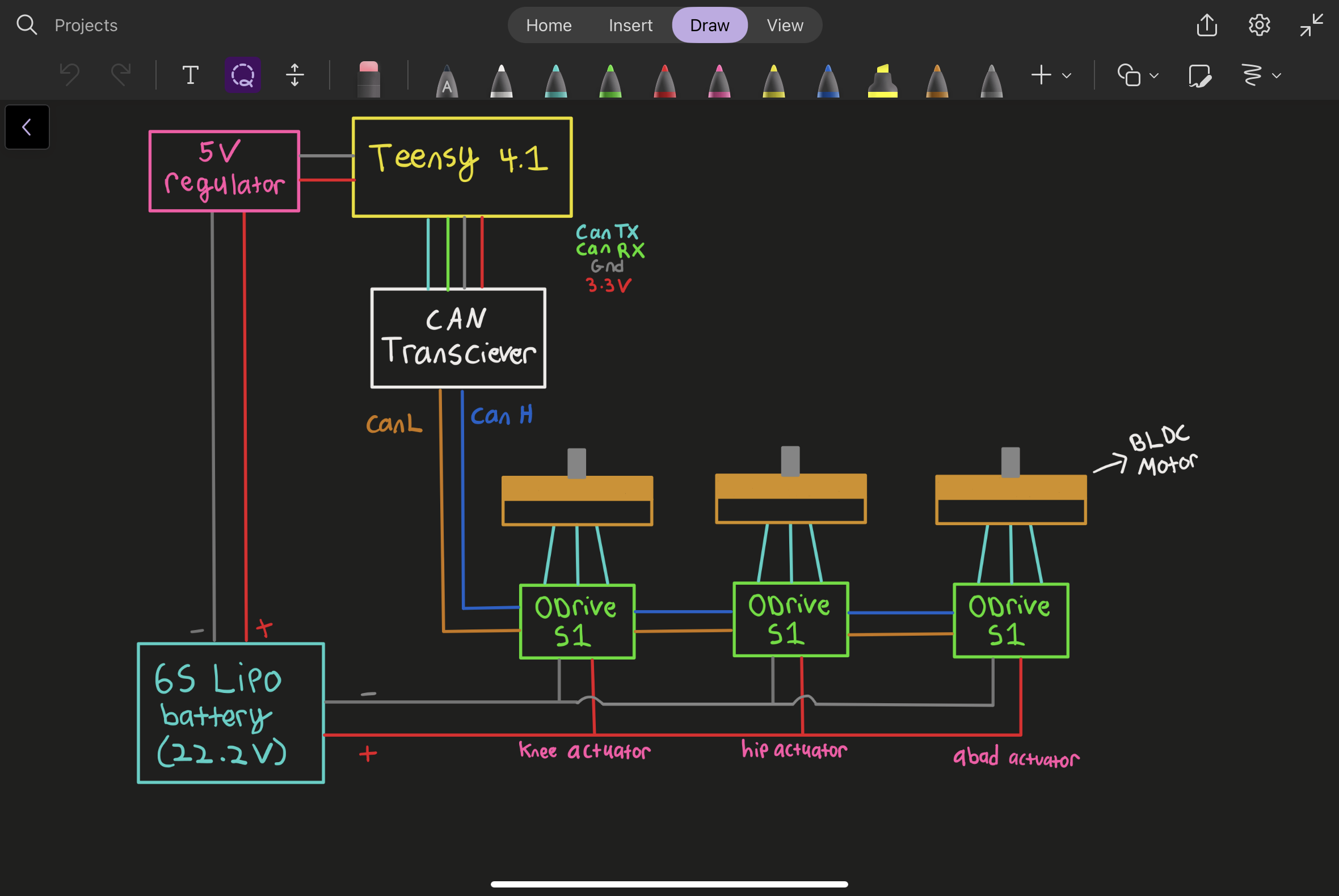

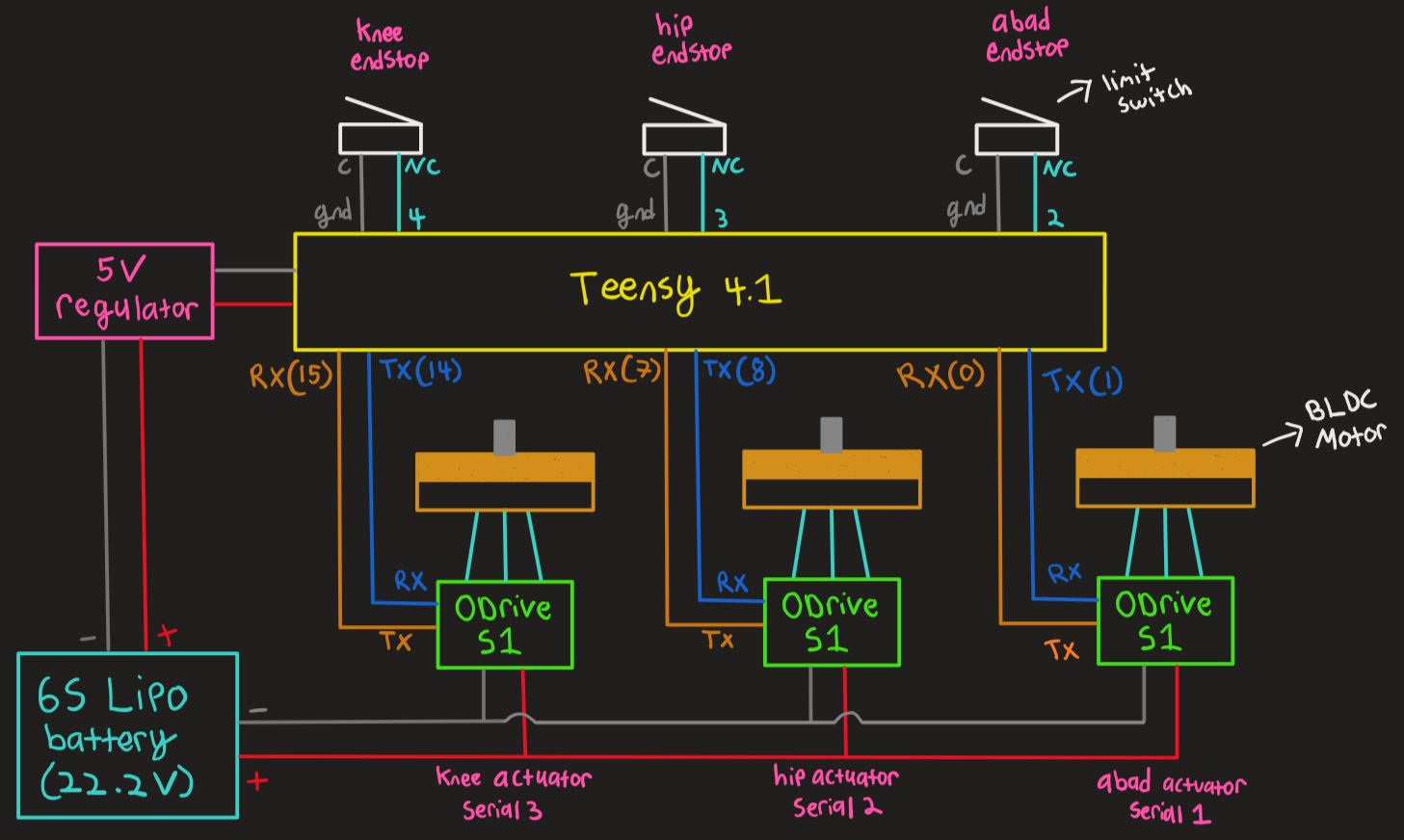

Electronics

All 12 of the actuators are powered by a 6S 5200 mAh Lipo battery. The actuators are also Daisy chained together via the CAN LOW and CAN HIGH lines which connect to the CAN bus transceiver which connects to the Tensy 4.1 microcontroller.

I'm using an RC remote and receiver to control the robot as well as a small 16x2 LCD to act as a menu for different control modes. Both of these also connect to the Teensy. The Teensy is powered by a 5V regulator which steps down the battery voltage. On the left side of the robot, I've attached a voltage display to monitor the battery life.

Programming

Programming this robot was the hardest part of the build. There are so many different variables to consider like the amount of time each leg is off the ground, how far the legs lift off the ground, how big each step is, the step trajectory etc.... These factors not only determine if the robot can walk in the first place, but how dynamic that walking motion is.

The main principle in getting a quadruped to walk is to always have a pair of 2 diagonal feet in contact with the ground at any given moment, this is otherwise known as trotting, and it's what allows TOPS to maintain balance.

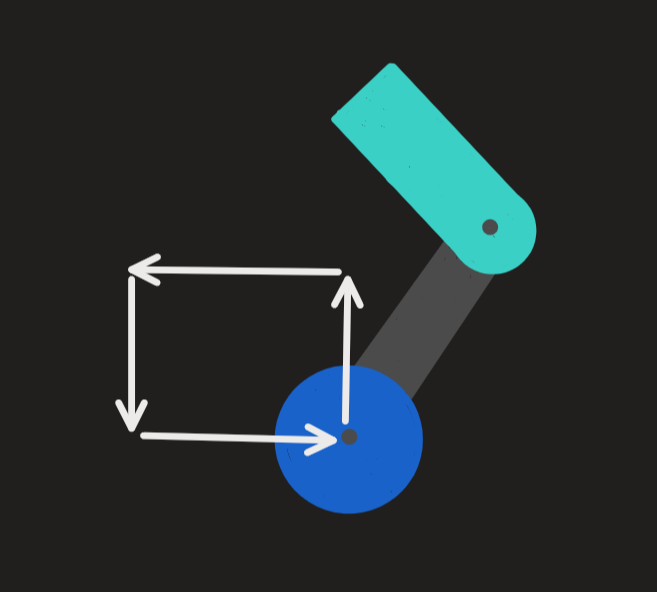

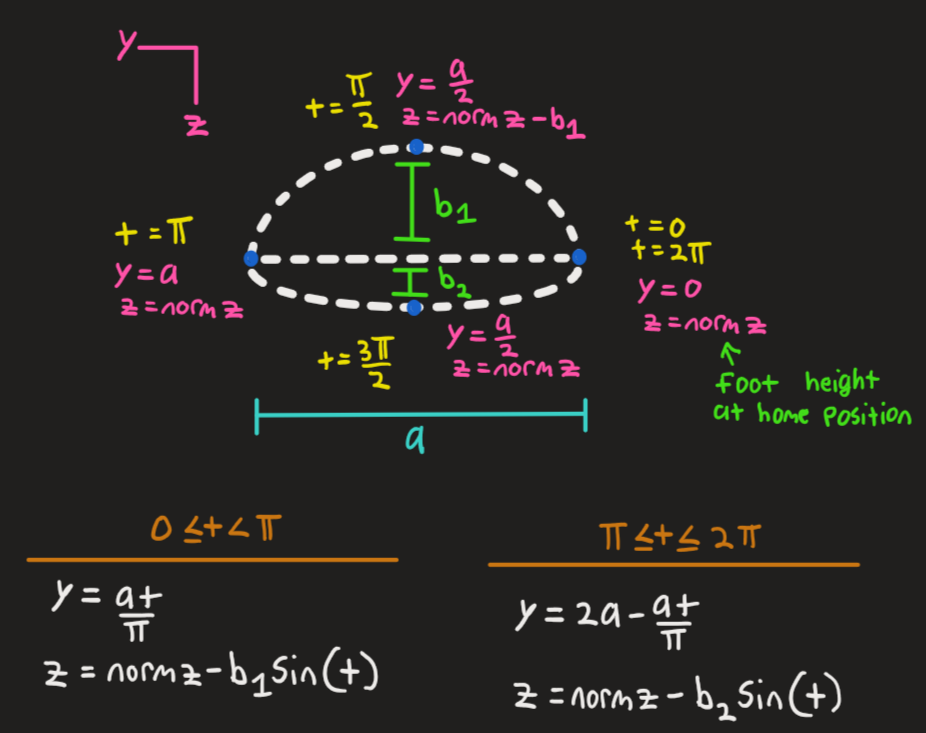

I had originally planned for a sinusoidal step trajectory, but it just didn’t work out so I reverted to a more crude but reliable square-step trajectory. Here the foot moves up, forward, down, and back.

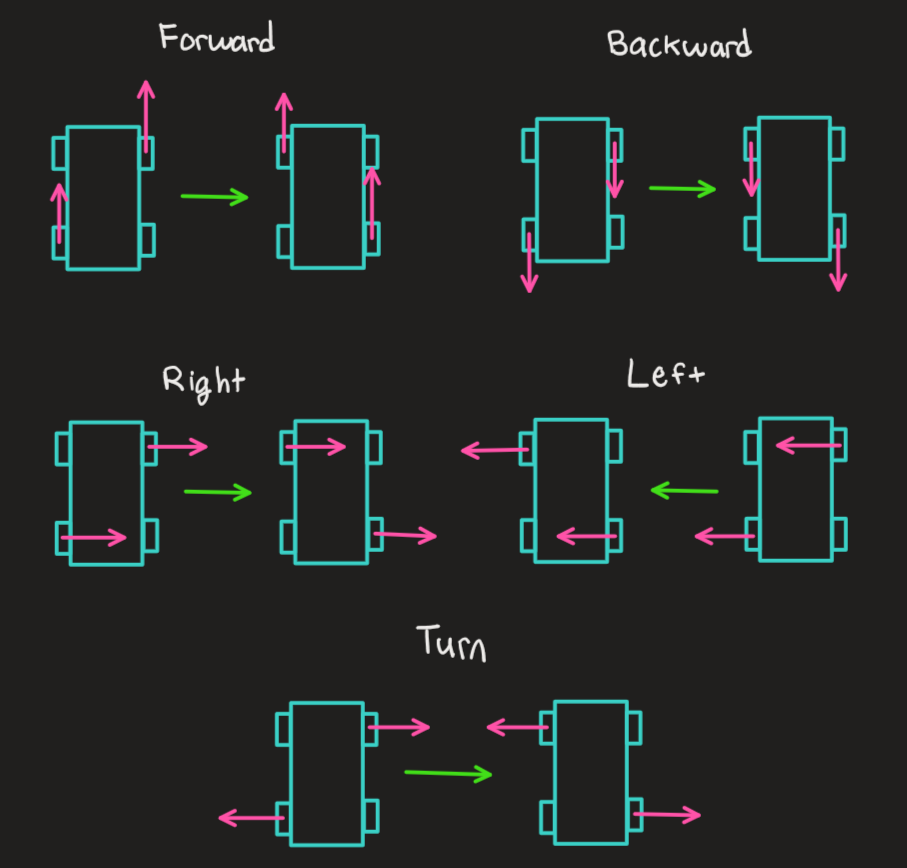

Now getting the robot to trot forward is essentially a 2-step sequence. You first need to have two diagonal feet take a step and as soon as they touch the ground, have the two other diagonal feet also take a step. If you keep the same sequence but have the feet move backwards, then the robot moves backwards. If instead of backwards you move the feet right or left then you get the robot to move sideways. The only motion that may not be as intuitive is turning. Here you actually want diagonal feet to move in opposite directions.

Overall Assessment

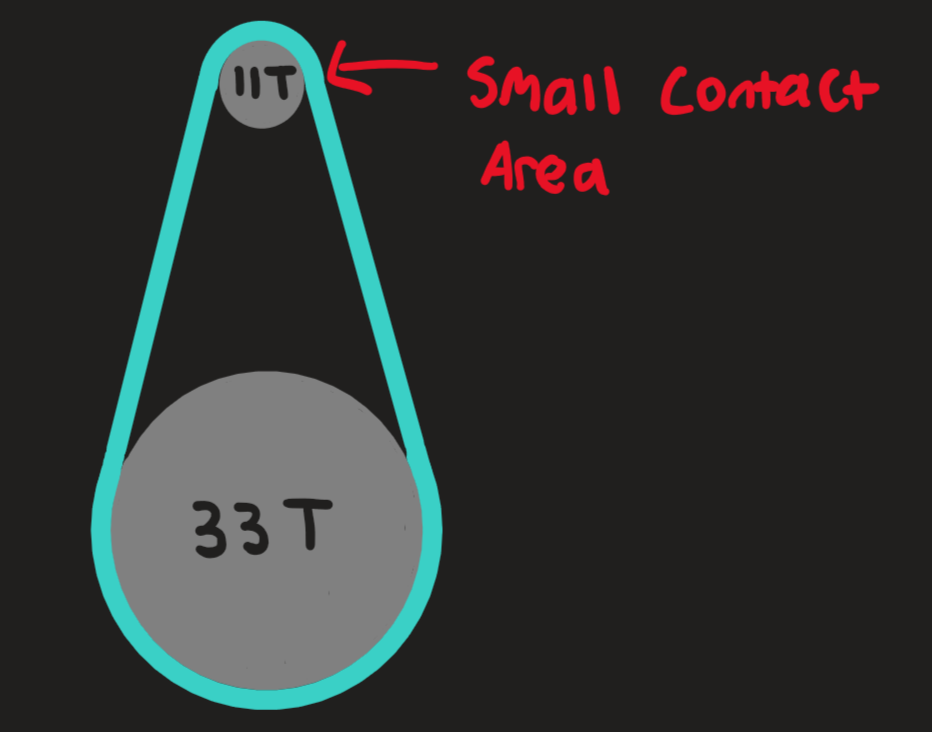

There are so many hardware and software issues that I almost considered not finishing this project at all. The main limitation on the mechanical side is that the knee joints skip like crazy and this is mainly because I’m using small 11 tooth pulleys to create that 9:1 reduction which means that the contact area for the belt is really small. Because of this, the robot can’t do things like jump or take a hard step because when the belts do in fact skip I have to recalibrate the robot.

Moving on to software issues, I have to manually calibrate each leg on startup which gets really annoying really fast. The other software issue was just a lack of natural dynamic motion. Programming gait sequences is really hard, and my code was pretty minimalistic. I also didn’t use any IMU sensors so apart from the natural compliance with the actuators, TOPS isn’t really reacting to changes in the environment or external forces. I hope to fix all of these issues in TOPS V2 which I’ll be making sometime in the future.

-

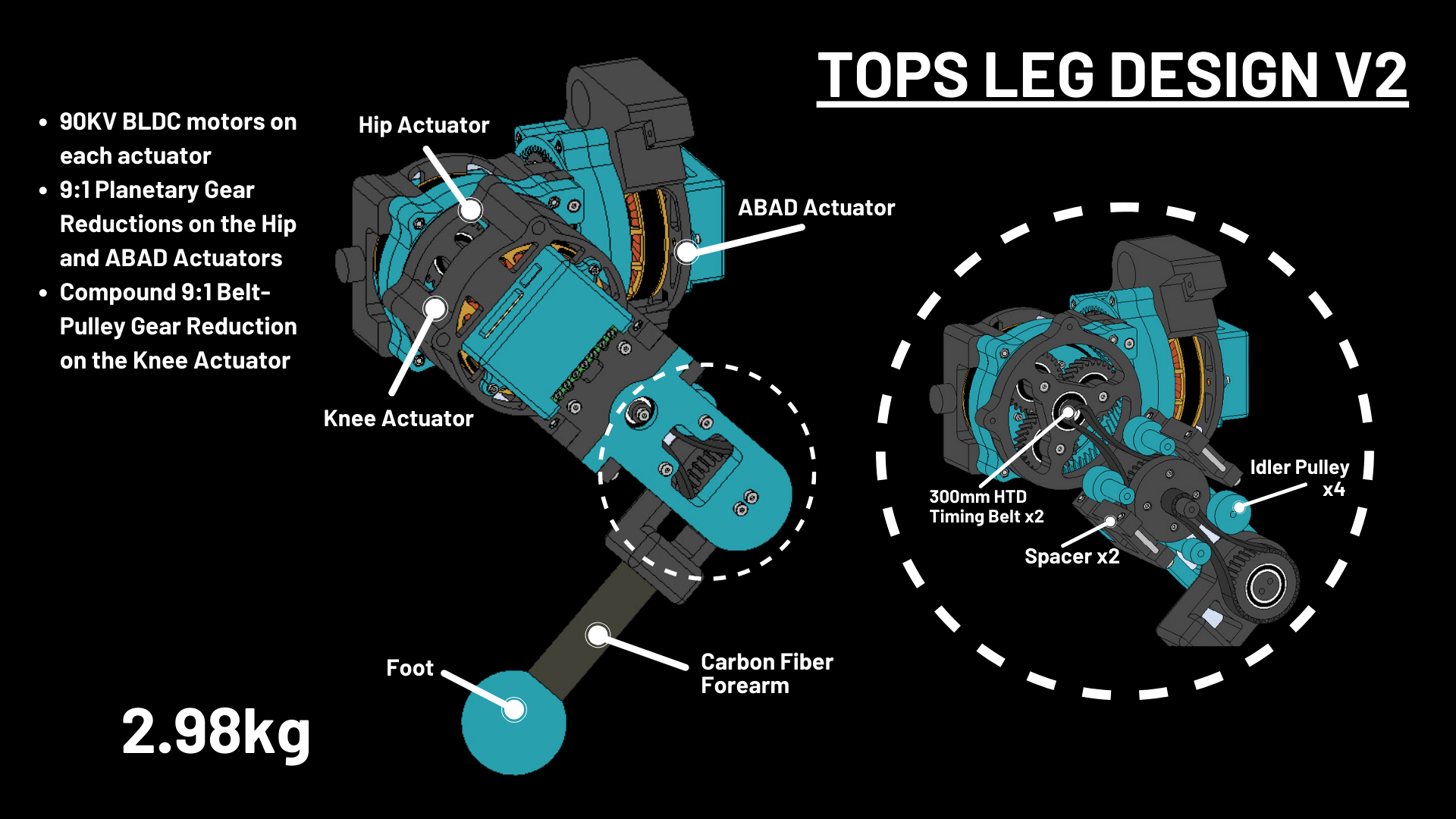

Leg Design V2

08/25/2023 at 20:09 • 0 commentsI’ve decided to redesign the leg before designing the full robot in order to address some issues that arose when testing out the V1 leg.

Physical Design Changes

- Got rid of using limit switches for homing.

- Reduced total screw count and made it so that most of the leg can be assembled with just M4 x 40mm rather than assorted screw lengths.

- Took off about 1lb from the original design (V1: 3.42kg, V2: 2.98kg, 0.44kg or 0.97lb difference). Considering a full robot, I’ve now made it 4lb lighter which is quite significant. I’m estimating the total weight of the robot to be about 13-15kg. For reference, Spot from Boston Dynamics weighs 31.7kg.

- Made the leg design much lower profile by reducing how much the it sticks out.

- Reduced the complexity/print time of each actuator design. The BLDC motors are now visible which allows me to feel the motors when they get hot. It also just looks a lot cooler! The knee actuator had the most change. The knee actuator in V1 used 9:1 planetary gear set in addition to a 1:1 gear reduction for the belt pulley system to actuate the lower leg. Now, in V2, the knee actuator has no planetary gear set and a 9:1 reduction for the belt pulley system. This change was the biggest weight and size reduction.

Motor Control Changes

- Switched from UART to CAN BUS since the microcontroller that I’m using (Teensy 4.1) only has 8 out of the 12 serial ports that I would need to control 12 motors with UART on a full robot. With CAN BUS, in theory, I would only need 1 serial port to control 12 motors although it would be best to use 2 (6 per port).

- With CAN bus all motors are interconnected through two wires (CAN H, and CAN L) which significantly reduces wiring. For reference, with UART, each motor was connected to four wires for serial communication rather than two.

- The only limitation of using CAN bus is that the ODrive motor controllers that I’m using don’t yet have an official Arduino library for CAN bus so I’m not able to read the absolute position from the onboard encoders. This means that homing the actuators requires me to move the leg manually to a common position which I've integrated physical limits into the design.

Gait

- In V1 I created a stepping sequence called sine step which moves the leg forward by following the path of a sine wave and then moves the leg back to the original position by following the path of a straight line. This time, the leg moves back to the original position by following the path of another sine wave (of small amplitude) rather than the path of a straight line. This is the same gait trajectory used by the Stanford Doggo and I’m hoping that this further smooths out the gait.

Jump Testing

- Shaving off so much weight got me thinking about making the leg jump.

- I’ve got the leg to jump a little less than 3.5”. With four legs the robot should definitely be able to jump.

- One issue I ran into while doing jump tests was belt tensioning of the knee actuator. The knee actuator carries the most load, so its belts have to be extremely tensioned to so that they don't slip during a high-impact landing. Although I haven’t tested this, reducing the position gains, which increases actuator compliance, should increase impulse and help reduce impact upon landing.

Weight Testing

- I've got the leg to lift 10 lbs meaning that the robot should be able to lift 40lb, which shouldn’t be confused with how much weight it will be able to walk with (most likely less than 40lb). I did further testing with a scale and the leg should be able to lift up to about 13lb.

-

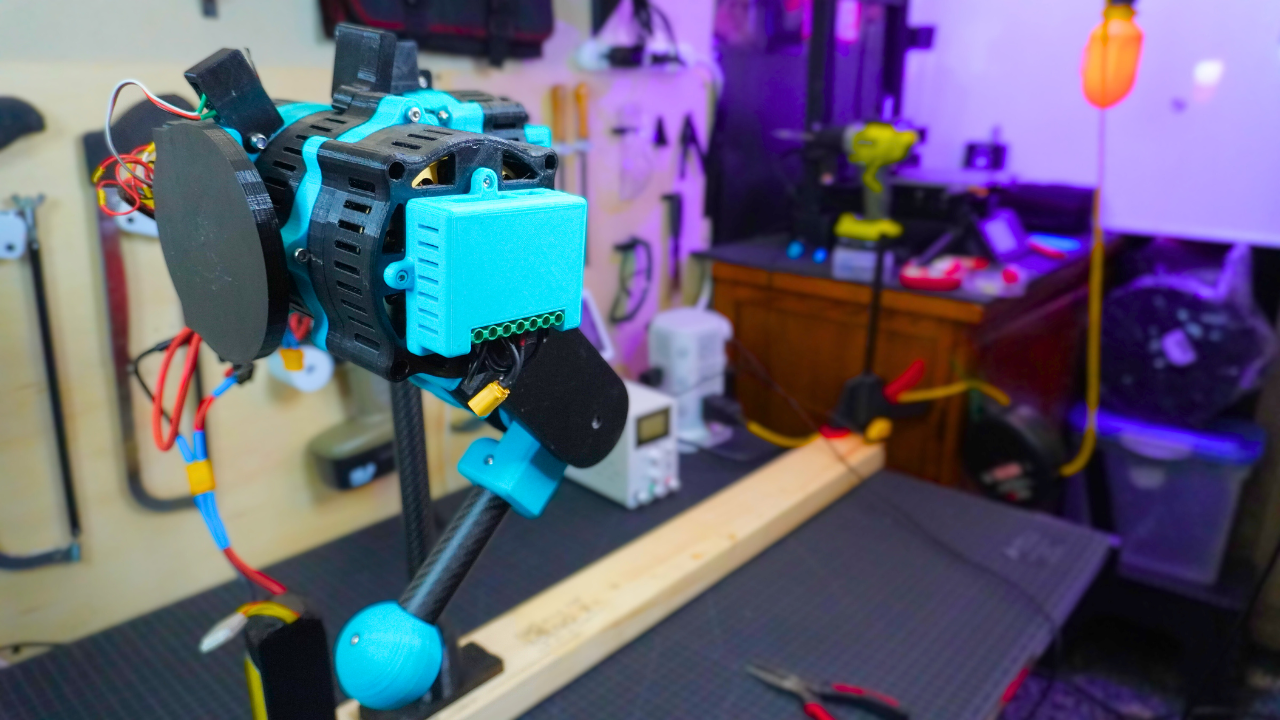

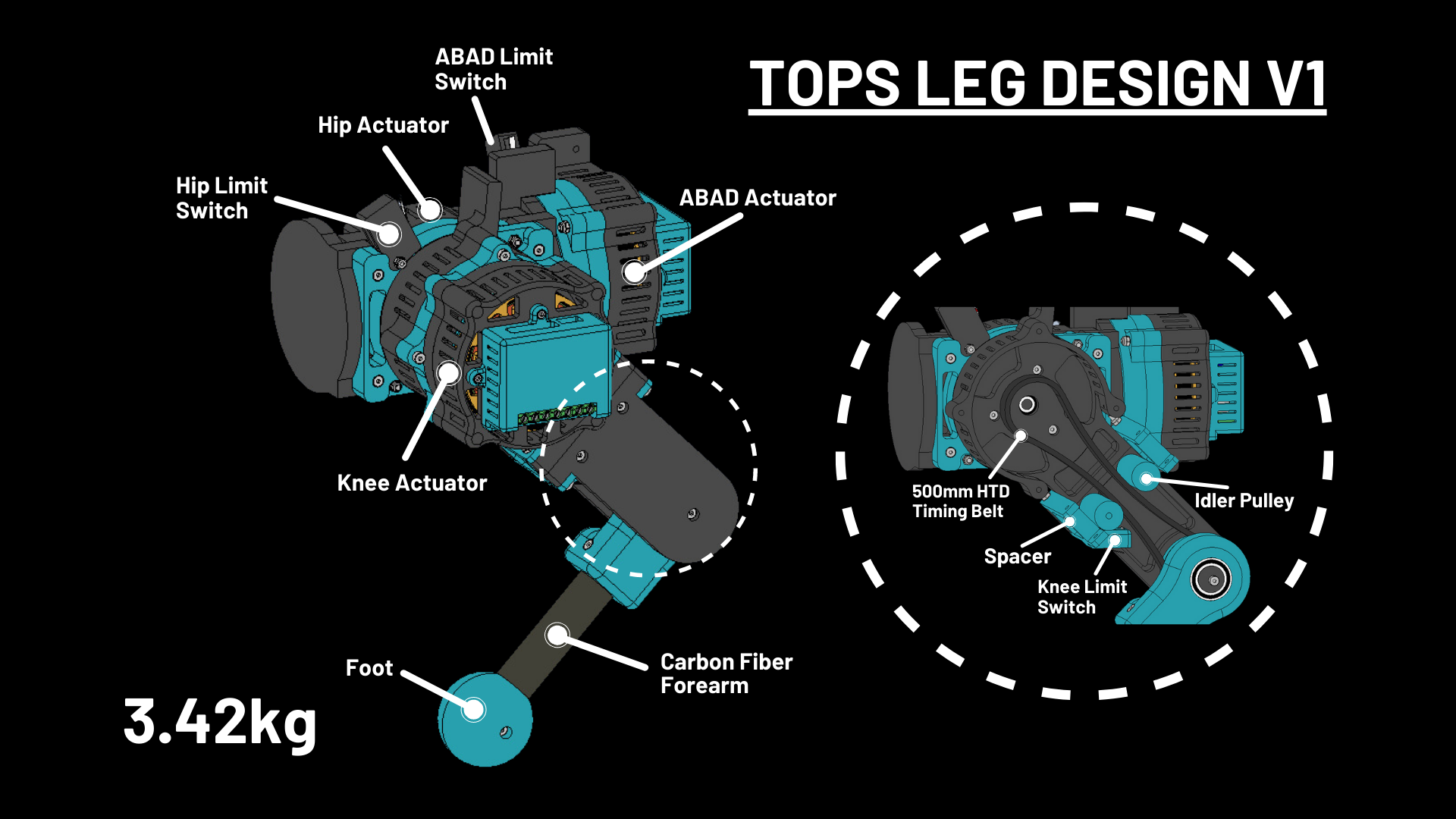

Leg Design V1

07/28/2023 at 11:18 • 1 comment- 3-DOF/ 3 Joints/ 3 Actuators (abad, hip, and knee)

- Each actuator has a 9:1 planetary gear set reduction

- Each actuator is a modified version of my OpenQDD Actuator.

- The leg design is integrated into the design of each actuator.

- The knee actuator uses a belt-pulley system with a 1:1 gear reduction

- Derived my own inverse kinematic equations called QIK (Quadruped Inverse Kinematics) to calculate the joint angular positions when placing the foot at a specific point in space.

- Made an Arduino Library for the QIK equations.

- Sinusoidal gate trajectory

- Weight: 3.42kg

-

QDD Actuators

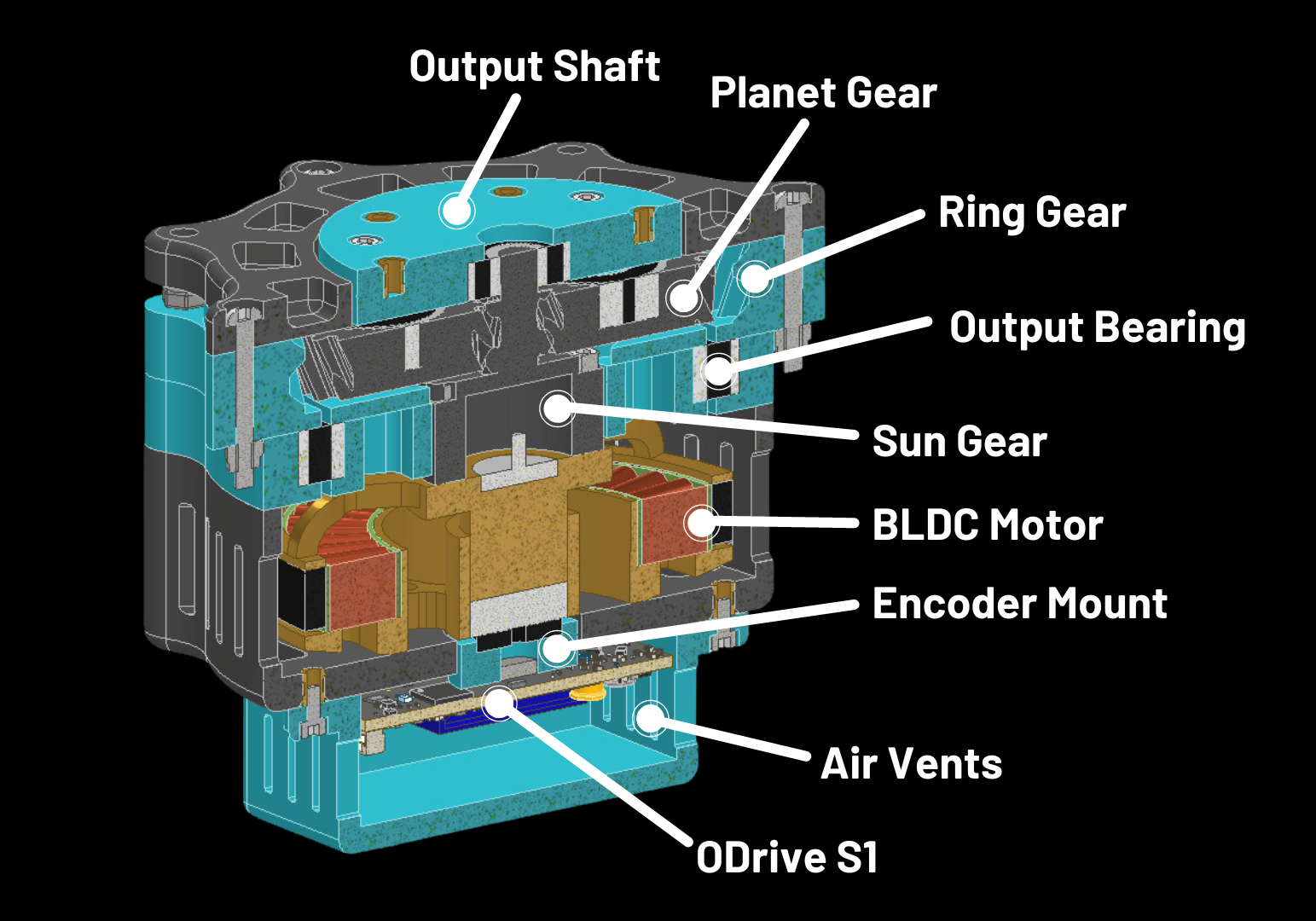

07/28/2023 at 04:07 • 0 commentsQDD (Quasi Direct Drive) actuators use brushless motors and have low gear reductions, high torque, and high speed. These characteristics make them ideal for developing walking robots. For this project, I’ll be using the QDD actuators that I developed called OpenQDD.

Specifications

- 9:1 Planetary Gear Set with Helical Gears

- ODrive S1 FOC Controller with an Onboard Encoder

- 13x 3D Printed Parts

- Air Vents for Passive Cooling

- Peak Holding Torque: 16.36 Nm

- Total Mass: 935g

- Total Cost: $247

Aaed Musa

Aaed Musa