PRELIMINARY

May 8th, 2024: It only got started.

version 2024-08-18

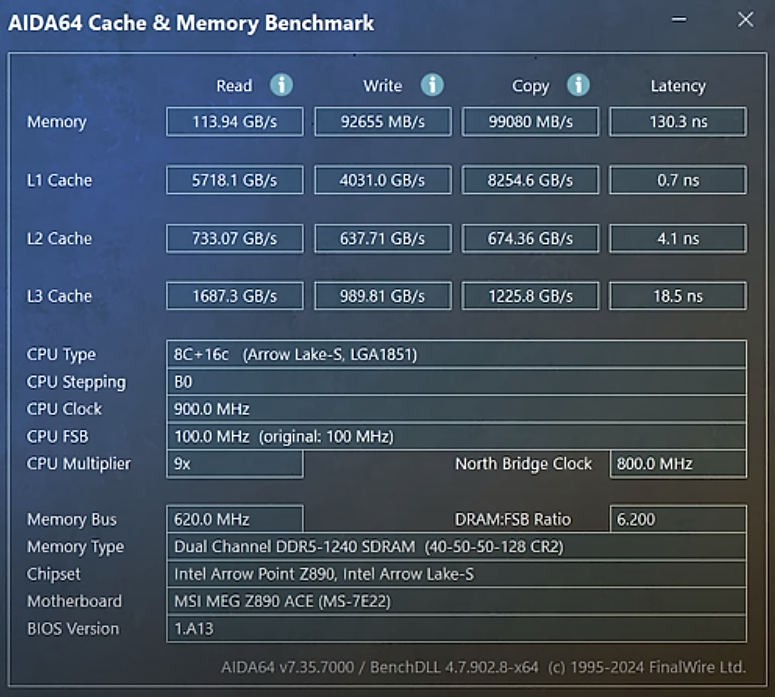

Class for comparison : i586 (no MMX), i960/i860, MIPS R3000 or R5000, SPARC V7/8 or LEON, RISC-V, ARM Cortex-R...

- Type : embedded safe/secure, 32-bit application processor for medium performance despite slow memory

- 32 bits per instruction

- 32-bit wide data words

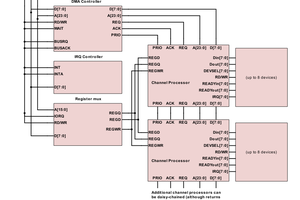

- 2 identical "globules" with 1 ALU, 16 registers and a dual-ported cache block each.

- register mapped memory : 4 address registers and 4 data registers per glob.

- CDI model: separate addressing spaces for Control (stack), Data and Instructions.

- 24 bits for instruction pointers, that's 16M instructions or 64MB of code per module. 2^24 modules are possible simultaneously.

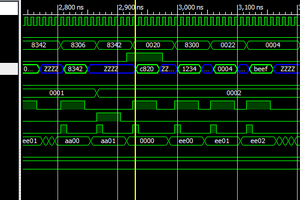

- 2 very short parallel pipelines for data processing and a 3rd decoder for control/branch/stack instructions: ILP can go up to 3.

- 8-entry "explicit Branch Target Buffer" with 8 more hidden/cached entries as well as 8 pairs of entries dedicated/linked to the control stack.

- Multitasking suitable for Real Time/Industrial OS, light desktop or game console workloads.

- Heavy computations are offloaded to suitable coprocessors.

- Powerful tagged control stack

- Some high-level single-cyle opcodes (and combinations thereof) provide basic control structures.

- Resilient, safe and secure by design

- Floating pooint ? Maybe later, we'll see.

- Need 64 bits, more registers or SIMD ? Use its big brother the #F-CPU FC1 (tba)

- Too overkill ? Use a microcontroller like the #YASEP Yet Another Small Embedded Processor (16/32 bits) or even the #YGREC8(8 bits).

- Spoiler alert : it is not designed with Linux-friendliness in mind.

Rationale:

For now I'm only collecting and polishing the ideas. Several years ago I considered a streamlined YASEP with only 32-bit instructions but it would have broken too many things. The YASEP (either 16 or 32 bits) resides at a particular sweet spot but can't move significantly outside of it. OTOH a 32-bit mode for F-CPU would have been interesting but still too ambitious : F-CPU is a huge system so even implementing a simpler subset implies already having the whole already well figured.

So YGREC32 is not really a cleaned-up YASEP. The use of a dedicated control stack does not fit well in the YASEP which will remain a "microcontroller". The YGREC32 is an application processor for multitasking environments that will run user-supplied code, even potentially faulty. It is still suitable for real time but not heavy lifting. It could be simultaneous-multithreaded for even better efficiency. Yet YGREC32 binaries would be easily executed by FC1 with little adaptation since it's mostly a subset, with half the globules and smaller words. Upwards compatibility/translation of YASEP32 is also possible.

A redesigned, pure 32-bit processor is a clean slate where I can develop&experiment with several methods such as #A stack. It becomes the first architecture to explicitly implement and develop the #POSEVEN model. It will be a shaky ride but hopefully it will help further our goals.

-o-O-0-O-o-

Logs:

1. First sketch (and discussion)

2. Second sketch

3. eBTB v2.0

4. a first basic module.

5. more details.

6. Indirect branch

7. How fast can it run ?

8. Globule symmetry

9. Data Stack protections

10. Restructuring the instruction bundles

11. Perverting RV

12. aligned access

13. Instruction grouping

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

.

.

......

Yann Guidon / YGDES

Yann Guidon / YGDES

Szoftveres

Szoftveres

Erik Piehl

Erik Piehl