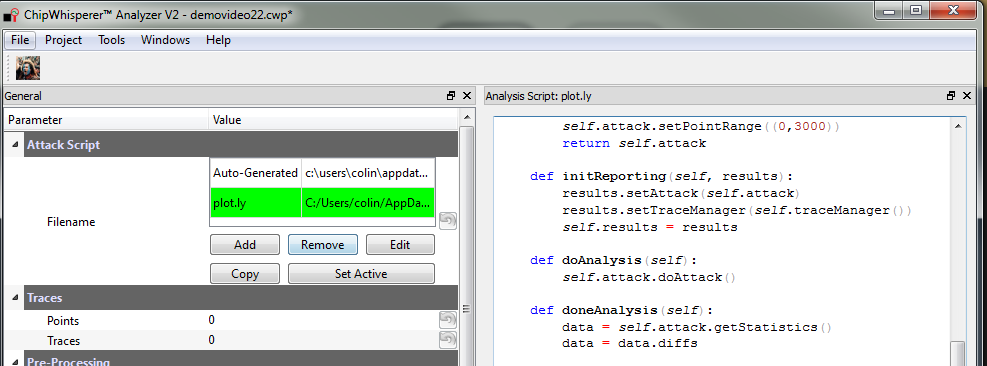

Links to project details (GIT, Wiki, Docs) are on the left. The laziest intro to this project is the 2-minuite video created for THP Quarterfinals (i.e. the first video I made):

Or even better, see my full 5-min final video (there is also the semifinal video, see link at left):

The most commitment is reading this page! Well if you are still reading, strap yourself in...

What's This About?

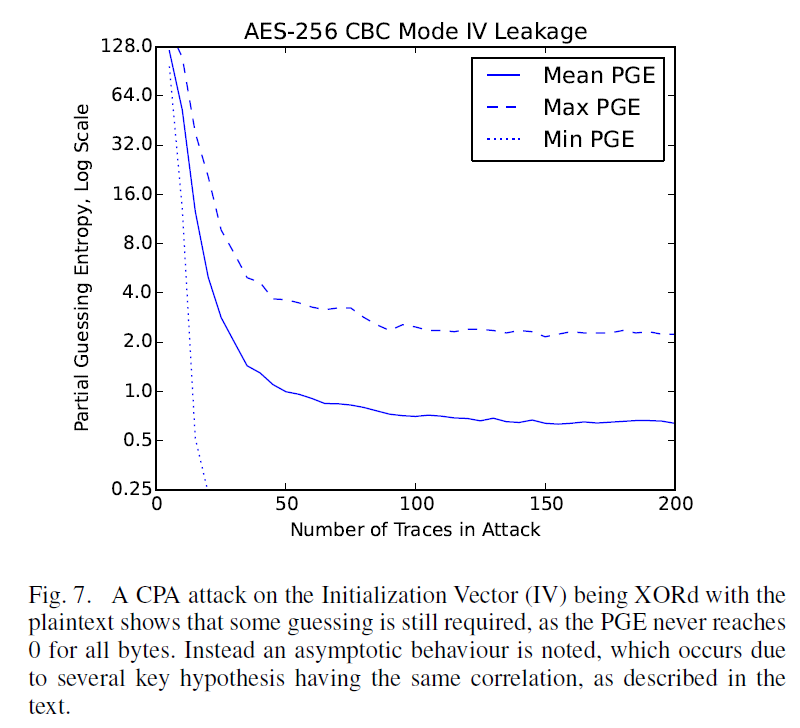

Lots of people have tried to design secure systems, and alas there is lots of failures. But what if you did everything correct: no buffer overflows, no unsanitized inputs, no default passwords. Unfortunately this isn't good enough - even perfectly implemented encryption algorithms such as AES-256 will reveal encryption keys. It's not due to incorrect implementation, it's a fundamental artifact of the design.

This has been known for a long time - the first paper on this was published in 1998. But if you are an engineer or independent researcher tools to get started are expensive, or require you to do a lot of work yourself scripting together lower-cost tools. This project is my attempt to eliminate this problem.

I'm eliminating the problem for good by making my tools open source. Because this whole area is an active research area, the tools need to be open source. This isn't a case of attempting to seem sexy by adding the word 'open-source', but placing something of commercial value into the open-source domain, in the hope it spurs a larger community. Think of something like Wireshark - it's extremely valuable, and could easily be sold as a high-end product. But most of that value comes from it being open source, and hence containing a huge array of protocol dissectors, far beyond what a commercial vendor could support. For my designs, part of the larger community includes hours of tutorials on this area - the objective of ChipWhisperer is not just the engineering that went into the software and hardware, but having tutorials and documentation that could be used as a complete course in side-channel analysis and glitching.

It's also worth stressing that there is no 'tricks' to the open-source nature of this project. It's not just part of the design that's open source, I'm not using a restrictive non-commercial license, and I've already had other people build these units from PCB design files. The objective of this is project is to open up this area of research to a much wider audience, and the commercial value I lose from limiting how much I can charge for the tools (since anyone can make them) is far offset by the greater value added to the community.

It's useful to point out how critical this field of embedded security has become, and why it's interesting to see attacks against AES (which I tend to focus on in my demos). The 'Internet of Things' requires some wireless communication network - be it IEEE 802.15.4, ZigBee (which uses 802.15.4), or Bluetooth Low Energy. Since these are wireless protocols, security is of paramount importance - and the designers acknowledge that. Attacks against AES are interesting because all three of the previous protocols use AES-128 for security. Unfortunately AES-128 isn't just a "check box" that indicates your system is secure, despite one document listing that because Bluetooth low energy has 128 bit AES, it's "secure against attack and hacking" (see page 45). The idea that implementations are secure because the underlying algorithm is secure will cost somebody a lot of money when it blows up in their face, and they have to fix millions of already deployed devices.

Assuming designers aren't foolish enough to send encryption keys over SPI (see Travis Goodspeed's attacks), and have actually done the implementation correctly, and haven't introduced backdoors, we can still break the AES implementation. This isn't a theoretical attack, but a real-world attack that every embedded designer needs to understand. It's clear that very few designers are aware of this issue, based on how infrequently it is brought up when looking over datasheets, design specifications, and application notes. And no, it's not enough to use hardware accelerators - an attack has been demonstrated against the XMEGA crypto engine (presentation slides, details on page 77 of thesis, article at ACM behind paywall). See the 2684 pages of Bluetooth specification for example, not a hit for 'side channel' to be found:

ChipWhisperer won't secure the internet of things. But it will hopefully jolt people into believing that "secure because math" isn't a good enough answer. Even these theoretically unbreakable cryptographic algorithms have great weaknesses during implementation, and they may be much easier to break than you ever assumed. So let's start looking into how this works.

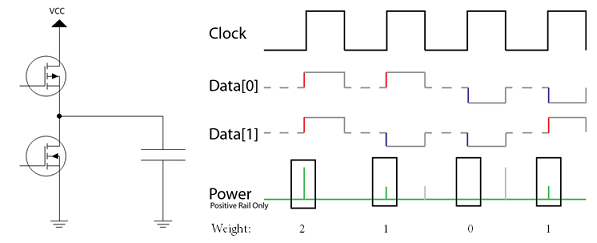

Side channel analysis takes advantage of the fact that changing the state of a digital line uses a small amount of power. Switching from a 'zero' to a 'one' takes a small charge for example. Many digital ICs will also push the lines into a 'pre-charge' state in-between transitions to reduce the worst-case time delay, such that on every cycle the bus goes from an intermediate state to a final state. For us this means we can almost directly infer the Hamming Weight (number of one's) on a digital bus based on the power consumption.

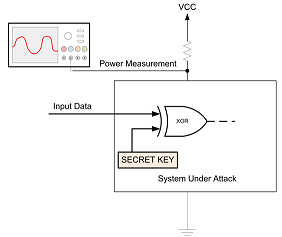

So what does that give us? Consider that we had the following system, which is a simple XOR of some input data with a secret key, where we don't see the final output:

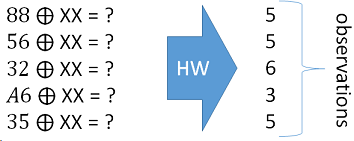

While we can build the following matrix, given some known inputs, along with the associated hamming weights based on the power measurement:

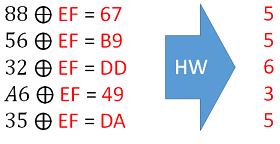

Then one can simply guess what the secret key was! Based on our guess we can determine which guess best aligns with the real measurements. In the following example if the secret key was 0xEF, we would end up with the hamming weight matching our observations:

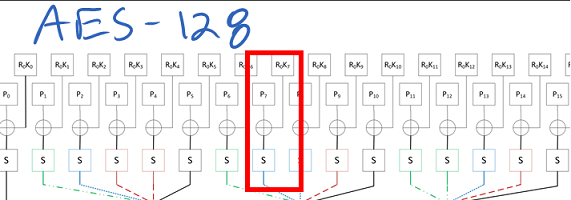

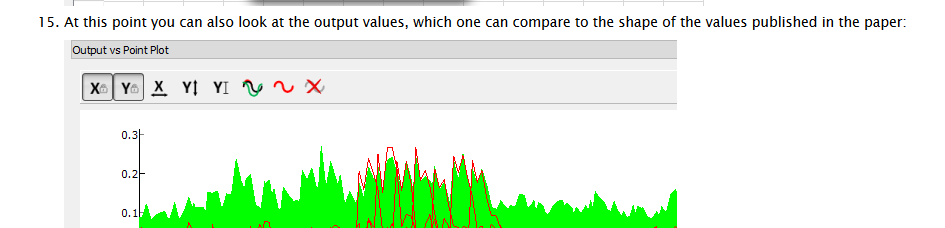

Finally, the reason this works so well is that it allows us to break a single byte of the encryption key at a time! Thus the minimal guess-and check means guessing 256 possibilities for each byte, and doing that 16 times:

For more details see my write-up on the theory of a CPA attack, along with a nice example of step-by-step breaking of the AES using Python from my ChipWhisperer tutorial list. For the attack to work, we basically just need to be able to tell the encryption/decryption algorithm to operate while we monitor the power, and know either the output or input to the system.

This can be done with ~20 power traces on an AVR device for example, so it's not a case of taking an unrealistic number of measurements. For example see a real-time example of me breaking an AES-128 implementation in 120 seconds.

Glitching is another devious attack on embedded systems. This takes advantage of the fact that at some point in your code you'll have a test of the input password, signature, or whatever else. So consider we have this code:

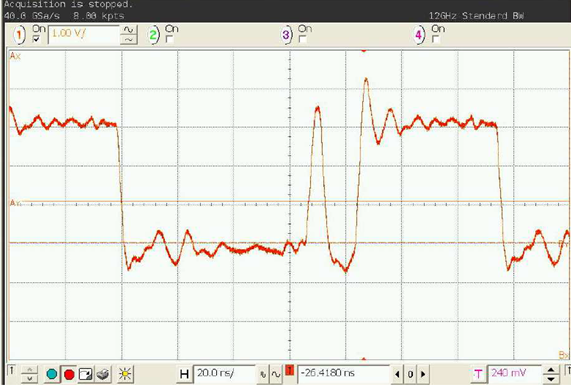

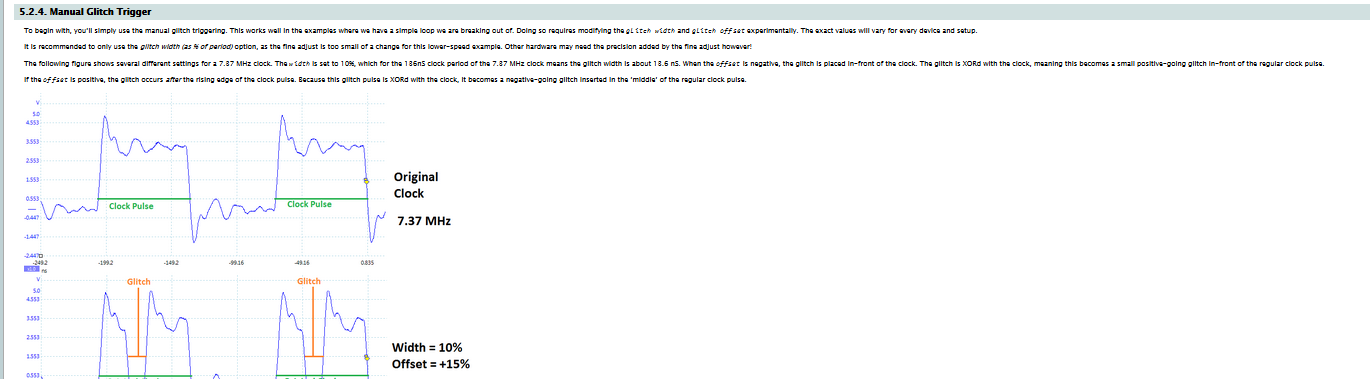

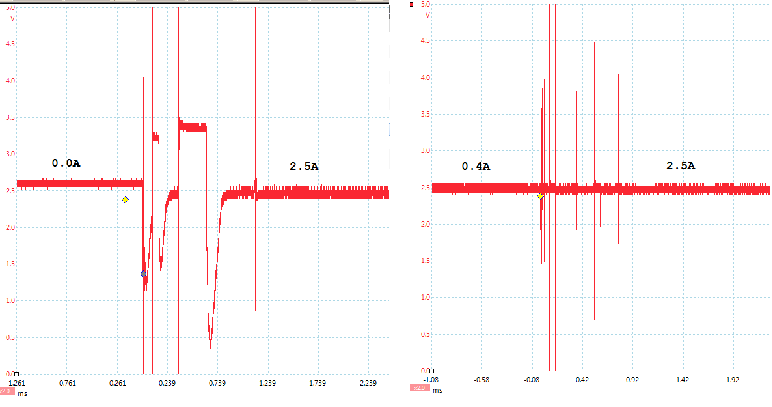

It's actually possible to manipulate the system to cause that check to fail, or for instructions to be skipped. One method of doing this is inserting a quick glitch into the clock, as the following example from the ChipWhisperer shows:

This "double-edge" causes timing errors in the target device. The result of this varies, but often results in an instruction skip or the wrong result of a comparison to be loaded. As an example see my video showing clock glitching breaking a password check.

If you are looking for some additional detail see the full ChipWhisperer clock glitching tutorial, which includes a 35 minute video tutorial.

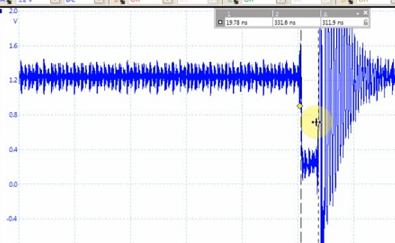

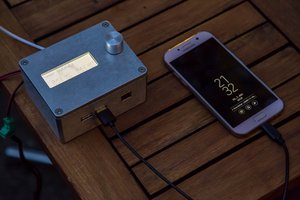

Even somewhat more interesting, is the fact you can do this with 'power glitching'. This means inserting some sort of low-voltage spike into the VCC line of the device you are targetting. This works even for advanced chips, like a Raspberry Pi or Android Smartphone. The VCC line glitch might look like this:

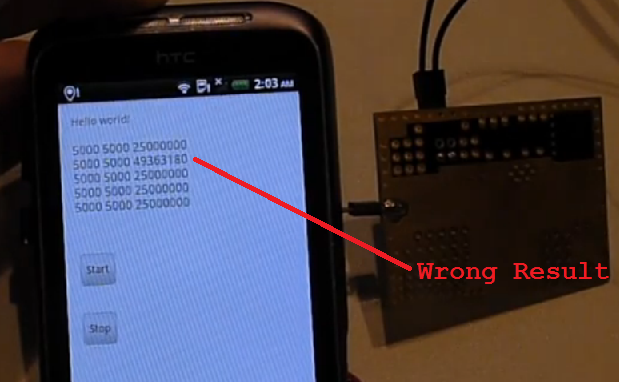

This can cause a user-land application to fail on something like an Android smartphone - here is an example where I'm causing an incorrect calculation, this example comes from my project log update:

There is a full ChipWhisperer VCC glitching tutorial which targets an AVR microcontroller, in the same fashion as the clock glitching tutorial. Now that you get an idea of why these attacks are so interesting, let's look at what ChipWhisperer can do.

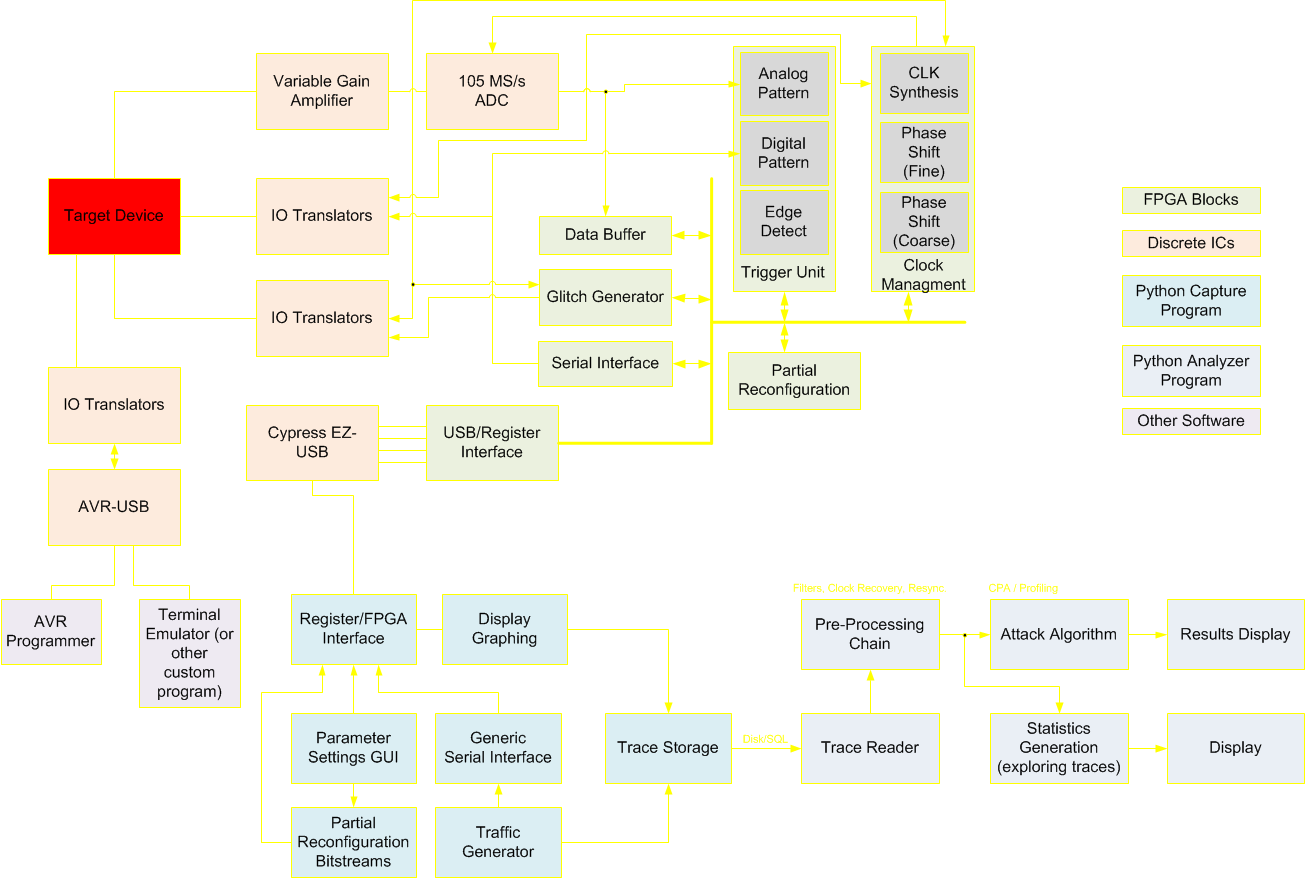

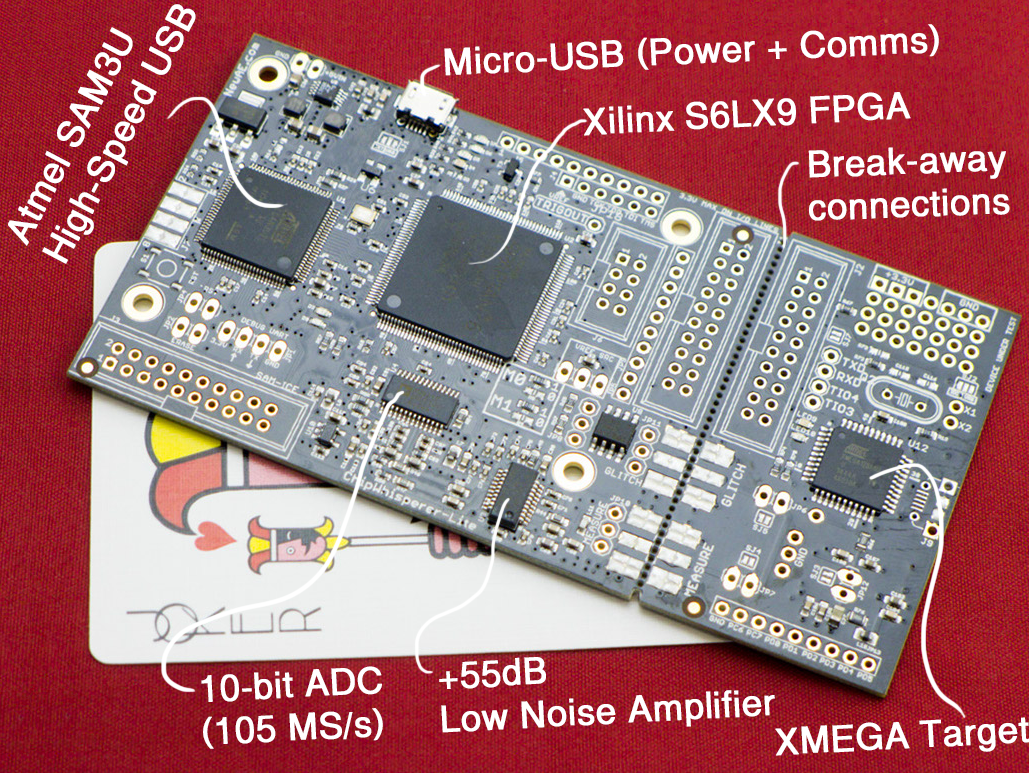

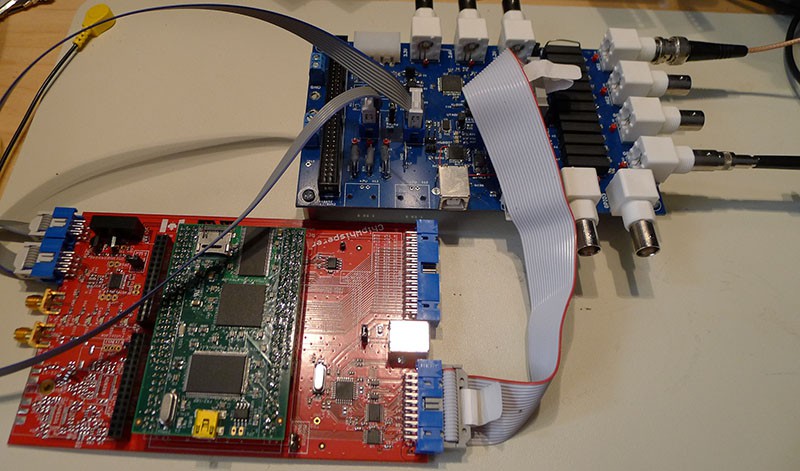

The system is a fusion of closely operating FPGA blocks and a Python interface communicating over a high-speed USB 2.0 interface. It even uses partial reconfiguration to reprogram the Spartan 6 FPGA during operation to fine-tune certain parameters that would otherwise be fixed when implementing the FPGA. Remote database storage of traces is used to power high-performance analysis, levelling the playing field for the independent researcher who doesn't have access to costly computing hardware.

Having the computer connectivity of the hardware is fundamental to the operation of this device. In addition it's possible (and sometimes required) to have the device split over several locations via a network. This can mean the ChipWhisperer is running on one computer, with data being saved to a larger network store. Even for researchers who do have local access to a high-performance computer, the remote storage is often useful, since the physical attack may be occurring at a different spot from the analysis computer.

The blocks themselves can be implemented into many different FPGAs - this system is not limited to the capture hardware created as part of this project.

This project has spawned a number of useful modules, some of which are already being used in other open source projects. The following section briefly summarizes some of the hardware modules, software modules, and techniques which I created for ChipWhisperer (but are useful for a variety of open-source projects).

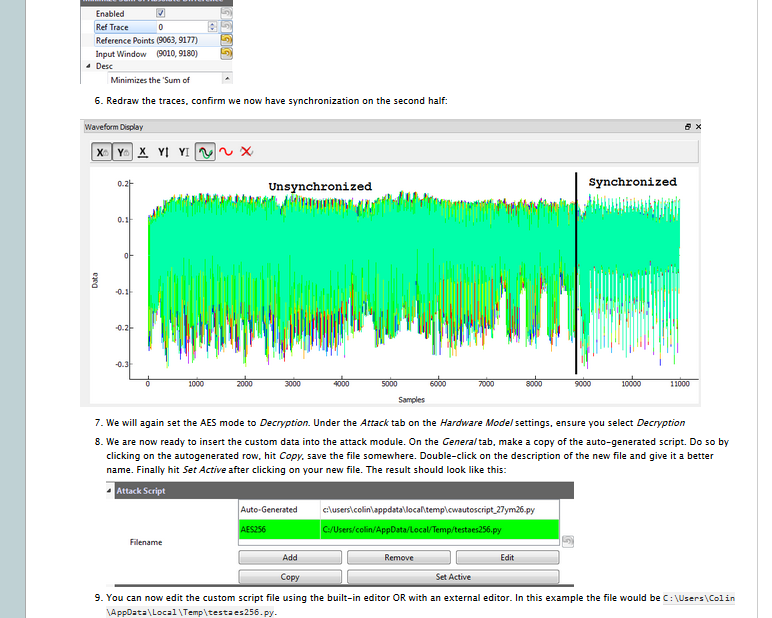

Synchronous Sampling: The synchronization of the sample clock to the device clock fundamentally differentiates the ChipWhisperer from commercial solutions, even the extremely expensive ones. This allows the ChipWhisperer to break systems that would otherwise require 5GS/s or faster oscilloscopes according to published academic papers. Currently the ChipWhisperer is the only solution (commercial or otherwise) using synchronous sampling with variable phase offset, allowing it to attack devices with internal oscillators or with varying-clock countermeasures. The use of Synchronous Sampling is the basis for three academic papers (including a journal article), demonstrating the innovation of this technique. More details will be presented later.

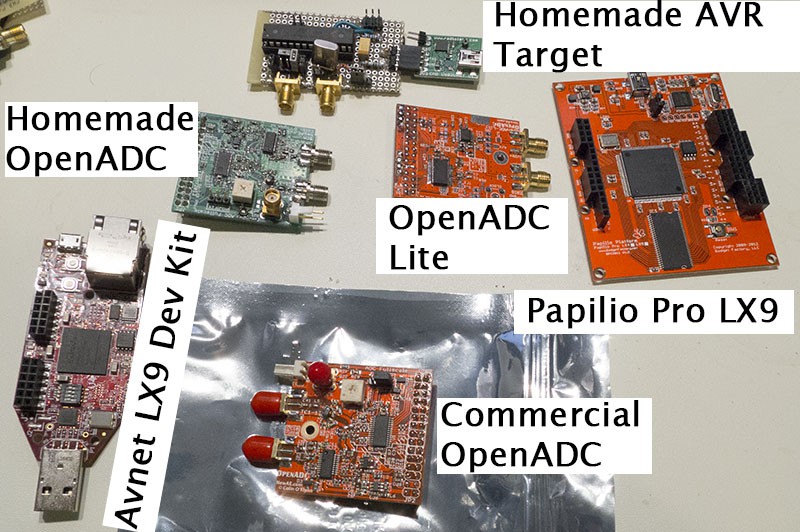

OpenADC: The OpenADC was the first module created, and is the high-speed ADC block. In addition I've published the FPGA code for storing samples and downloading those samples to the computer via Python. Besides my academic papers using the OpenADC, I've found a few other papers (1, 2, 3) using the OpenADC for doing research into low-power wireless networks and crypto. It's extremely exciting to see my work being used already! More details of the OpenADC are given later in this description.

PyQtGraph Parameter Tree Updates: This project uses PyQtGraph for both graphing along with setting of parameters for almost the entire project. This involved some updates to the PyQtGraph implementations, specifically the ability of setting parameters to automatically download them to the hardware, and verify the setting in hardware.

FPGA Project File Generation: The Xilinx ISE Project navigator files are an XML based format, but have a serious problem when attempting to commit them to GIT: they change for every version of ISE! In addition you need different project files for each FPGA device supported. This causes many headaches: commit conflicts for different versions, along with maintaining multiple files for each project. ChipWhisperer uses a simple text file to automatically generate both the ISE Project file and associated COREGen files, see details in the log post.

FPGA SAD Trigger: The Sum of Absolute Difference (SAD) trigger FPGA block performs real-time pattern matching of a stored pattern to the incoming waveform. This means the pattern matching runs at the ADC speed (i.e. 105MS/s), and was successfully implemented in a low-cost (i.e. fairly slow) Spartan 6 FPGA. This would be trivial to do in software, but unacceptably slow and with jitter relative to the device clock. The FPGA block is able to detect a match exactly six sample clocks after the final sample of the pattern being digitized. More details of this are presented later.

FPGA Dynamic Clock Blocks: FPGAs provide various blocks for clock control, but typically expose a fairly complex interface. As part of my project I designed several modules that simplify this interface, allowing you to access the dynamic phase shift and dynamic frequency generation blocks. There is even Python code for automatically configuring the blocks given a desired output frequency for example, and the proper parameters are dynamically downloaded to the blocks. In addition this system supports an advanced feature called Partial Reconfiguration to allow you to dynamically tune all features of the clock module blocks, even a number that according to Xilinx are fixed at design-time.

FPGA USB Interface: A classic problem in FPGA designs is where one needs to control a few registers from a computer. I designed my own interface for this, which can run on almost any other FPGA development board, provides the ability to almost max out high-speed USB when downloading data, and has a simple Python interface. More details of this are presented later.

Waveform Plotting: The ChipWhisperer requires high-speed plotting of many waveforms. This is primarily handled by the PyQtGraph library, but that library has been extended to support additional features such as a dock with a toolbar for accessing various plot functions. Like most of the ChipWhisperers source it's all very modular, meaning you can rip that waveform display code out for something else.

When starting this project, it was destined to be open source. ChipWhisperer does not aim to be just a complete tool, but also a useful platform for further research. For example I assume 99.5% of users will never modify the FPGA code, and couldn't care that it's open source. But there is still that 0.5% - and the value of the open-source code to that 0.5% is what makes it worthwhile. So who are the 0.5%? I assume they would mostly be researchers; the area of embedded hardware security is an extremely active research area. There's a number of conferences and journals in this area, and researchers in this area are no strangers to FPGA work, or even designing custom chips. For that 0.5% of users, this project could save them from months to years of work (since they don't need to redo my work).

The core Python code is more likely to be modified (since it requires less effort than the FPGA design), but even then I've tried to make it as easy to 'hack in' extra modules as possible. I know from experience that of those that DO wish to modify the code, they will mostly want to get something working quickly. This is part of the reason the code supports all sorts of dynamic Python execution and loading of external modules (discussed in detail later).

By sharing the ChipWhisperer design, it provides a useful starting point for these researchers to build upon. If you decided to work on a real-time analysis algorithm implemented in an FPGA, the ChipWhisperer would be a perfect platform for your work. In addition the platform is commercially available, meaning that when researchers disseminate results based on the ChipWhisperer, it's trivial for someone else to duplicate or verify the results.

I've already received feedback from people using portions of this project. The ADC board (OpenADC) has been used in a number of other projects, and I've even had people in other countries thank me for providing the designs, as it's difficult for them to import PCBs in their country. But since they had the design files, they could have them made locally without issue.

Having previous experience with open-source projects, I'm familiar with many of the issues that hit these projects. In particular documentation is often a problem. Documentation doesn't seem as sexy as hard-core engineering, but unless the project is well documented it has zero hope of continuing once the main developer moves on or is hit by a bus. ChipWhisperer has a massive documentation repository, and it's still growing as this project is in it's infancy! Let's look at that next.

There are several main sources of documentation:

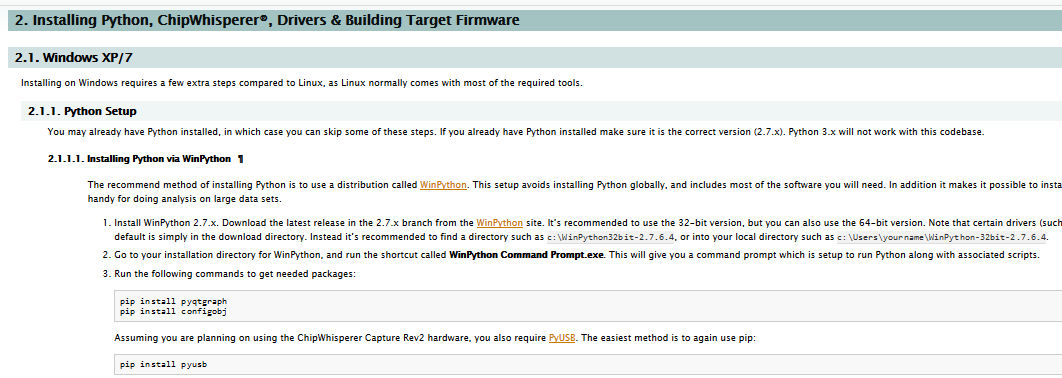

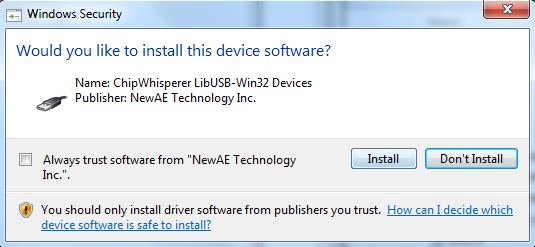

- Full Project Documentation: This is the major documentation, and includes both python API documentation, along with detailed instructions for installing python modules, using the hardware, etc. This documentation aims to be a polished resource.

- The Wiki: The wiki contains additional detail such as most recent releases, instructions for building hardware, BOMs, various small notes, and example traces. This aims to be a 'living' documentation so is subject to frequent changes, and has many short and simple pages such as PCB errata.

- Presentations & Whitepapers: There are a number of presentations I've previously given. The link to the left includes a few of the earlier Blackhat presentations, which have a long whitepaper too!

- Videos: I've got several hours of video tutorials. See the full list later on in the 'video' section of this document.

- The GIT Repository: Some people believe code is self-documenting. I've tried to help it along with docstrings and whatnot, but the GIT repository is the ultimate source for all things about this project.

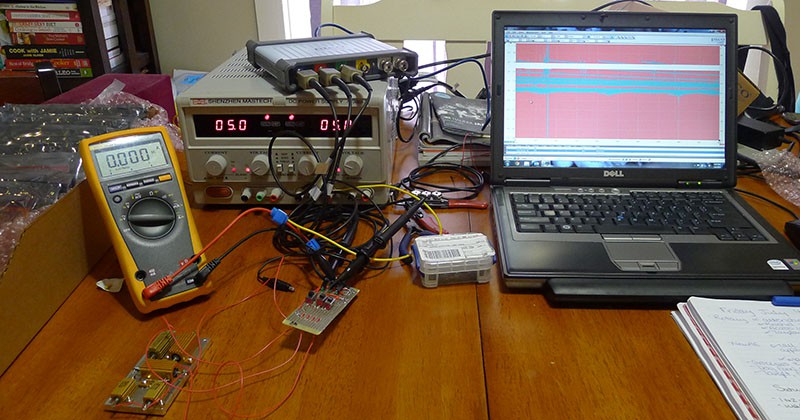

Here's a few pictures of the documentation:

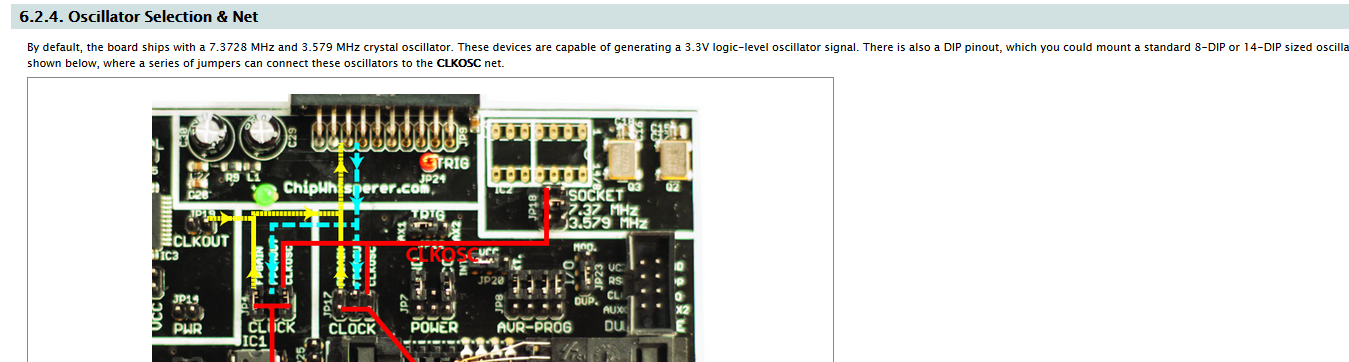

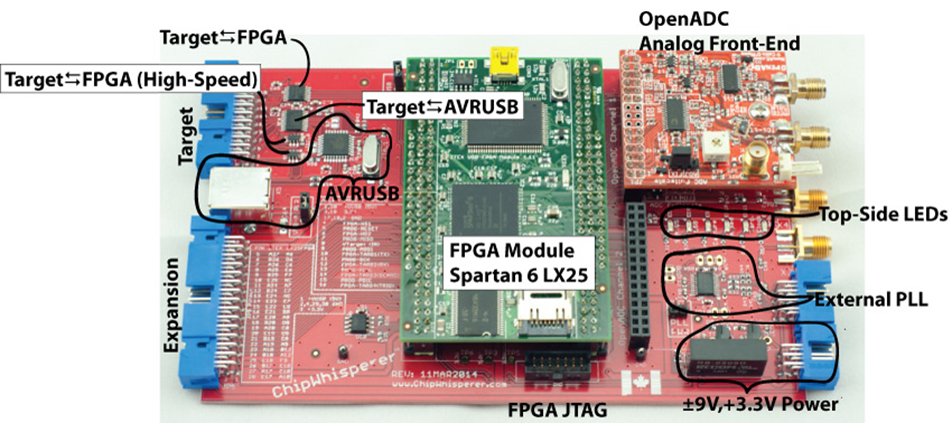

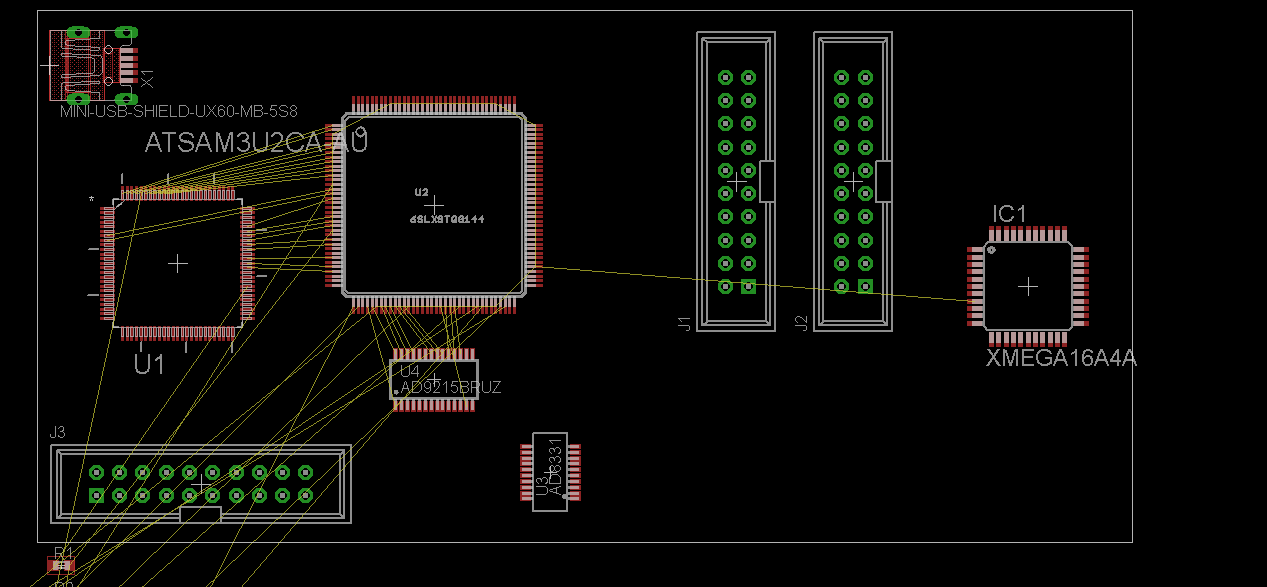

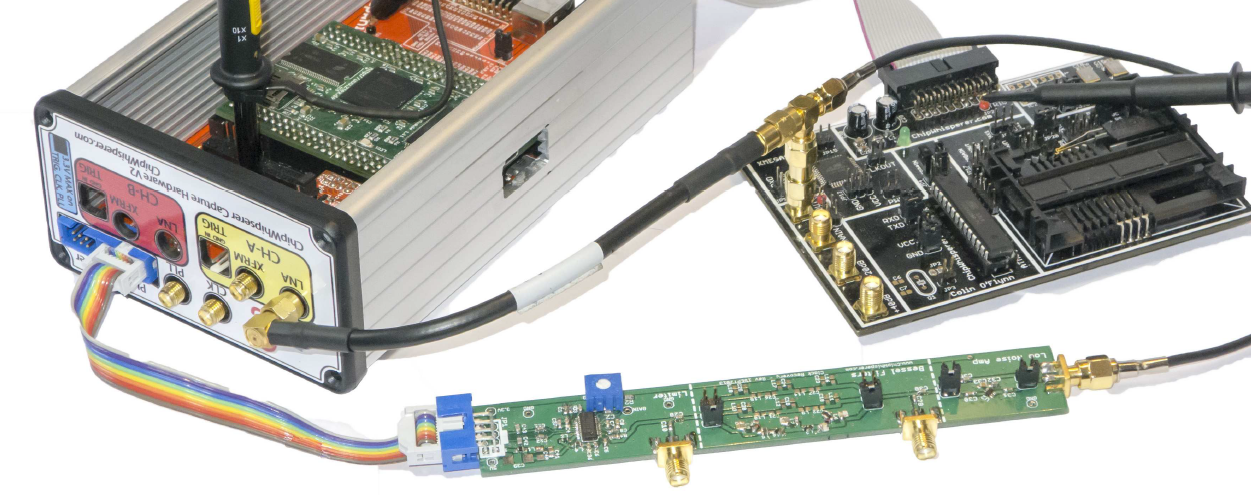

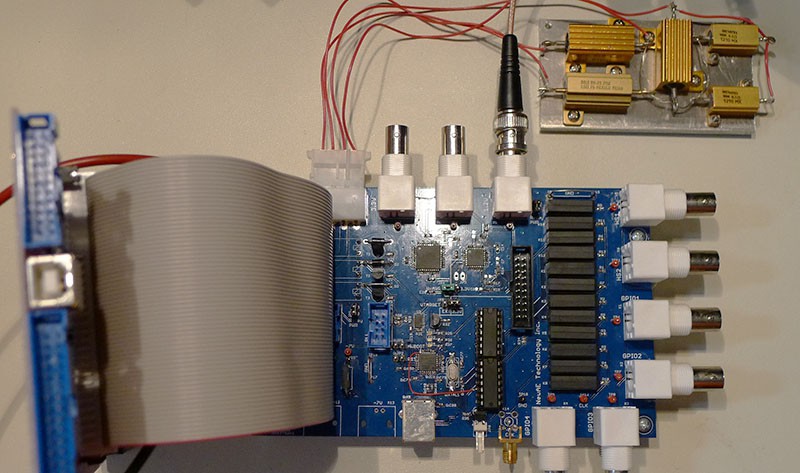

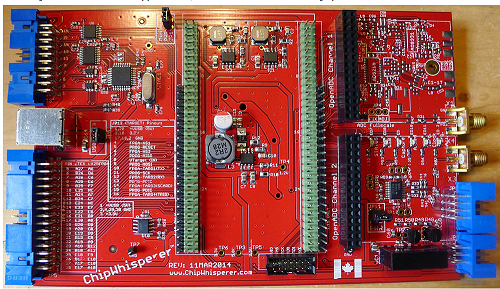

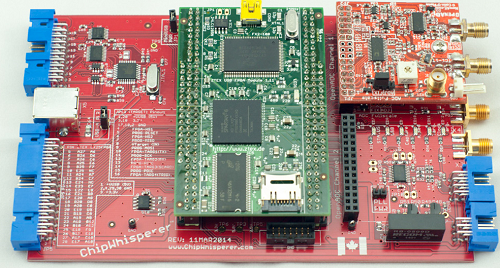

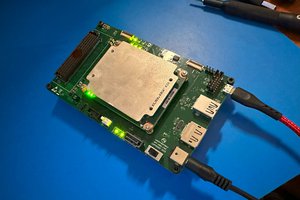

Some of the blocks on the main PCB are shown below. The OpenADC is my open-source ADC board which was designed as part of this project. The rest of the chips have various glue logic for easing interface to the FPGA, and a USB-connected AVR for 'additional stuff'. This can mean using it to program a target, talking some specific protocol, etc.

Target IO Interface

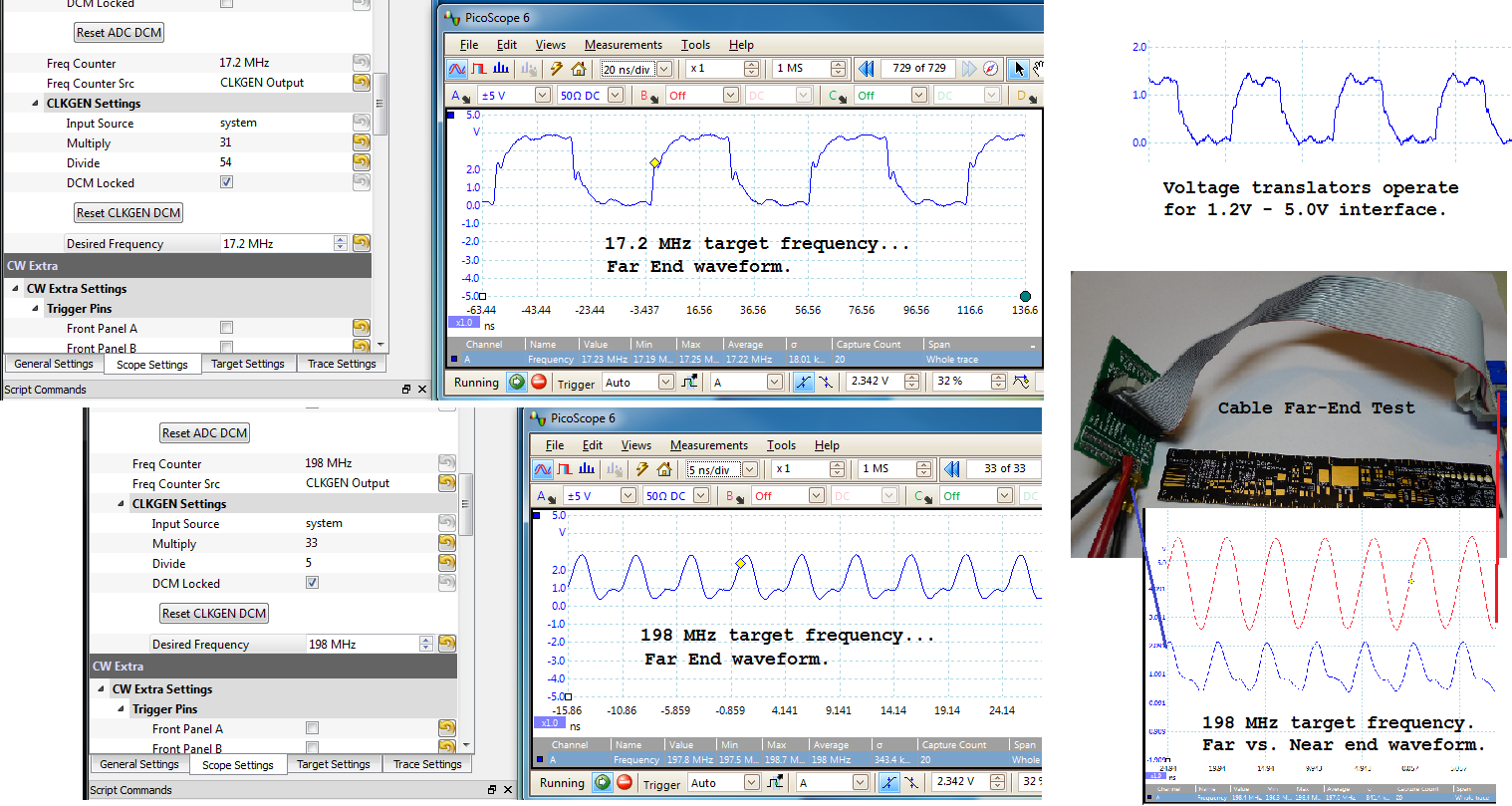

Twelve IO lines pass through level translators for use in a connection to the target device. Two of them use high-speed translators, which can be used for generating a clock to the target device, triggering a glitch, or receiving a clock from the target device. The ChipWhisperer can even be used as a simple clock generator for digital devices too - from the GUI a requested clock frequency is automatically generated by the internal clock module. Normally the output is fed over a standard ribbon cable. While not an impedance matched connector, for many experiments this performs 'well enough' in practice. The following shows some figures after 8 inches of ribbon cable. Note the 'near end' waveform taken at the back-side of the connector for the 198 MHz test frequency shows less duty cycle distortion compared to the far end waveform. This suggests using a shorter cable or designing a breakout board to plug into the header with SMA cables might be successful for high frequencies to reduce duty cycle distortion. The oscilloscope used in these tests had a 350 MHz analog bandwidth, meaning the 198 MHz waveforms don't have all the detail present (overshoot/undershoot + edges attenuated severely).

AVR-USB Connection

The AVR-USB connection is an AT90USB162 device. It can be programmed with a AVR-ISP MK2 clone firmware from the LUFA project, or can be programmed with other interface code such as my example USB-SPI driver. This allows for a complete development system, since you can use this device to program new cryptographic code into the device being tested.

FPGA Module Power Supplies

Originally, I wasn't sure if the LX25 FPGA would be powerful enough, so the system was designed to accept larger FPGA modules with everything up to a Spartan 6 LX150. These larger FPGAs require higher current sourcing capabilities, so the supplies were originally designed to meet these higher current limits.

As an example the 2.5V rail is being tested with an electronically switched (via a relay) load in the following figures. Some contact bounce of the relay can be seen, but notice there is little change in the noise on the supply rail even at these high currents.

Details of the test jig are shown in my project log update.

External PLL

Due to limits in the FPGA clock blocks, an external PLL is also present. Whereas the Spartan 6 clock blocks are spec'd down to an input frequency of ~5MHz, the external PLL chip can operate down to ~1MHz. This allows an extended input frequency range, in addition to providing a LVDS input path for the clock.

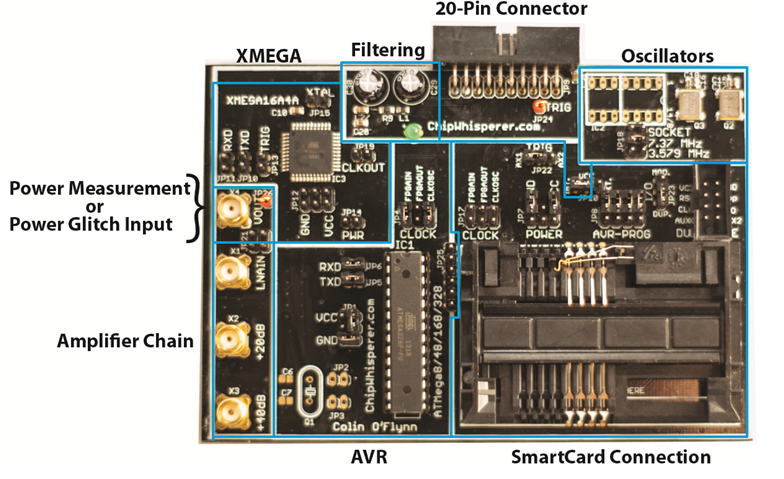

Multi-Target Victim Board

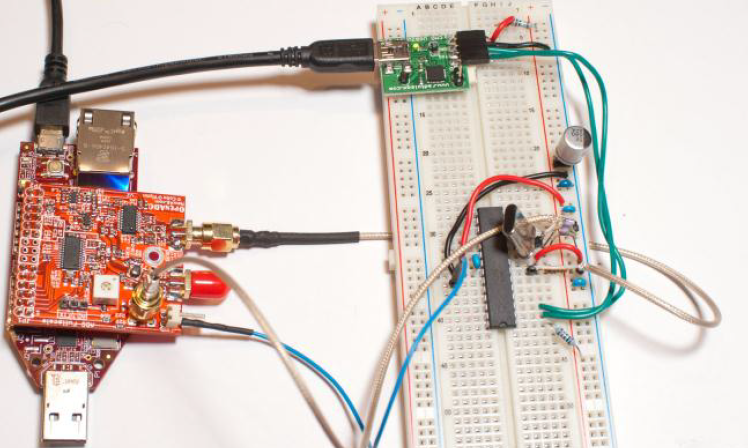

The multi-target victim board is a simple demonstration platform. This can be programmed with various cryptographic algorithms, and provides the ability to monitor power consumption and insert clock glitches. It can be used stand-alone with a normal oscilloscope (i.e. it is not tied to the ChipWhisperer Capture hardware) because of the Low Noise Amplifiers which can boost the small signals to levels a regular oscilloscope can measure.

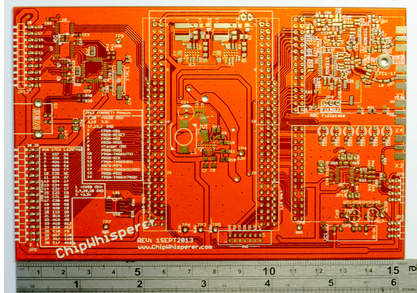

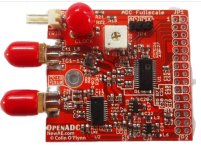

OpenADC

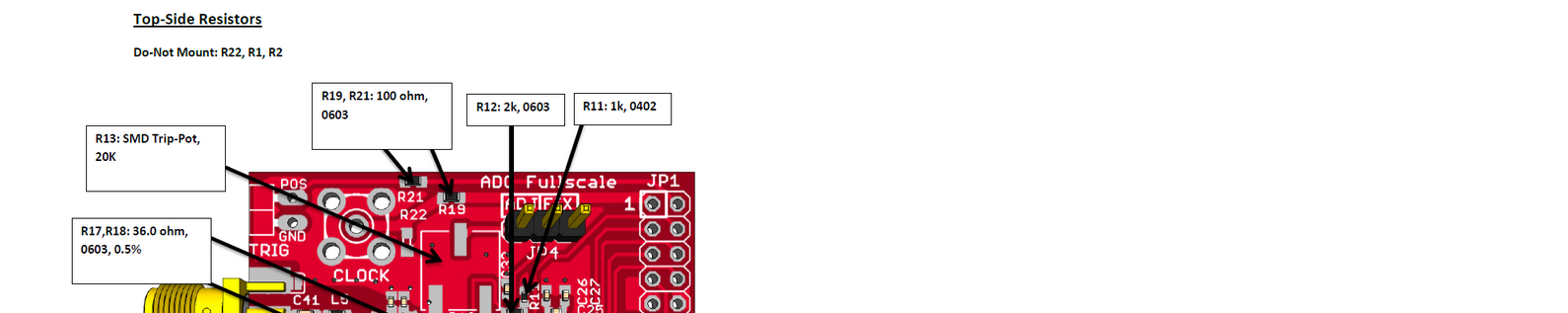

The OpenADC board is a modular ADC board. It uses the 'PMOD' connectors which are supported by a bunch of FPGA boards, especially those from Digilent. It's been designed to be fairly low-noise, and I've had a lot of positive feedback from that design! It's a simple 2-layer board, although it's been carefully routed such that the bottom layer is almost entirely ground plane, check it out:

There's no separate analog/digital ground, instead the layout tries to keep the analog and digital portions separated such that digital ground currents won't flow over the analog portions. I'd love to hear your feedback, but it seemed in my research that separating them can add issues with ground loops when the separation isn't 100% perfect (i.e. you run a digital trace over the analog ground, causing the digital return current to take a much longer path than it would have with a single plane).

The 3.0V analog supply for the ADC comes from an on-board LDO regulator, which filters the 3.3V input supply. The LNA chip required a 5.0V supply so there is also a 3.3V to 5.0V switched-capacitor based DC-DC on board. You'll see a number of ferrite beads (look at the Lx parts) that form supply filters.

The OpenADC has already been used in other academic publications beside my own. I have no connection with the following authors, I happen to discover their paper while searching my own references: (1),(2),(3).

Links to Schematics, Gerbers, BOM, Assembly Instructions

Everything is done with 2-layer PCBs to keep cost down. The following is a list of most of the hardware design files involved in this project, although see the GIT repository for full project design files, including beta/incomplete boards. Some of the links go to the GIT repo, and you have to hit the "Download" link to get a .zip of that folder.

The following are the "core" files which are used to build the ChipWhisperer Capture Rev2:

OpenADC: PCB Gerbers, Assembly Instructions/BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files, Datasheet with User Guide

ChipWhisperer Baseboard: PCB Gerbers, Assembly Instructions/BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files, PCB in PDF

Multi-Target Victim Board: PCB Gerbers, Assembly Instructions/BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files

The following are some bonus tools such as amplifiers:

Low Noise Amplifier: PCB Gerbers, Assembly Instructions/BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files

Differential Probe: PCB Gerbers, Assembly Instructions/BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files

The following are various device-specific boards:

Clock Recovery Board: PCB Gerbers, BOM, Schematic (PDF), Eagle Files

SAKURA-G Adapter Board: PCB Gerbers, Eagle Files

SASEBO-W SmartCard Adapter: Eagle File (board only)

Colin O'Flynn

Colin O'Flynn

Chance Reimer

Chance Reimer

Stephen Holdaway

Stephen Holdaway

psmay

psmay

Lukas Fässler

Lukas Fässler

Great project! How much does it cost you to manufacture it?

https://www.basmetelriyadh.com/cleaning-company/