-

In-Chamber Electronics

02/18/2025 at 18:47 • 3 commentsThe Current Status

At the moment, the system has no electronics inside the chamber, being purely mechanic. This was an initial design choice in order to simplify the initial design as a proof of concept. However, it's quite clear that the lack of any 'in chamber' diagnostics or feedback severely affects the whole system usability and reliability.

As the proof of concepts was partially successful, it seems appropriate to tackle the increased design complexity in order to improve the rate of development.

Goals and Constraints

Overall, the intention of the proposed modifications are:

Goals Solution Challanges Enhance deposition

qualityA resistive substrate heater is incorporated Heat Dissipation, high current input, requires temperature feedback, possible damage to the tape Make the system more reliable and autonomous Positional feedback on the mechanical components status High pin count, relatively difficult mechanical placement of sensors, perhaps signal conditioning considerations Film Diagnostics In situ electrical measurements,

Incorporation of a QCM sensorRequired rotational electrical 'pass through', signal multiplexing is a must, connectors are no trivial Due to the evident space constraints inside the chamber, the rather small amount of available flanges and the cost of electrical feedthroughs, I think it's quite clear that the way to proceed is to incorporate microcontroller(s) inside the chamber, which may reduce the pin count and allow signal transfer to the overall control system through serial interfaces.

At least in my experience with vacuum hardware, this is a highly unorthodox solution, probably due to contamination and heat dissipation concerns. For the vacuum levels I'm working, the contamination doesn't seem as big a problem as the possibility that my electronics might get fried without precious air to dissipate the heat they generate. But let's trust metal-cored PCBs (and perhaps some exotic potting compounds) may help.

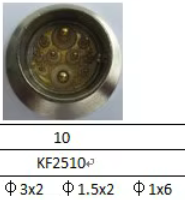

The final constraint is the amount of pins available in the electrical feedthroughs. I only have a couple of KF25 flanges available in the covers, and therefore I bought a couple these feedthroughs:

![]()

I have no idea about the current ratings, but I intend to use the thicker wires for the heater (which draws about 3A at 24V) while the 1.5 mm ones could be used to power the circuits inside.

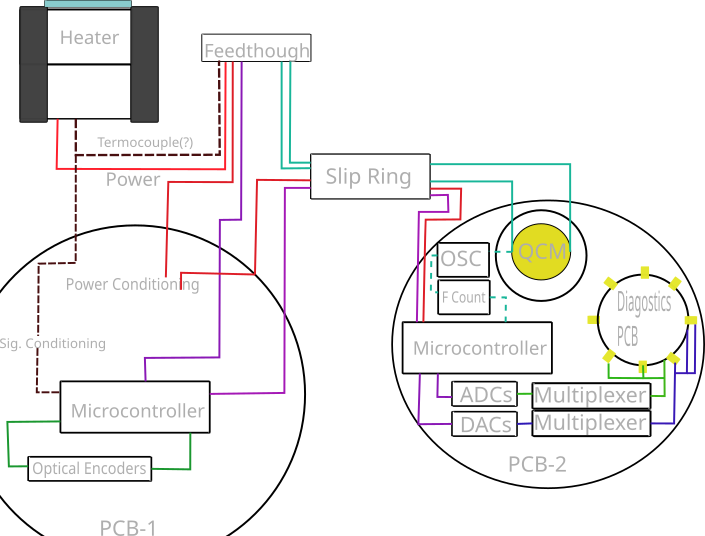

High Level Diagram

![]()

While I still haven't fully committed with all the components and design choices (should I try to implement the QCM oscillator and frequency counter inside, or rather just use an external dedicated instrument, for example), the overall system is based on at least two PCBs: One coupled to the feedthrough cover, which hold the main microcontroller, which should take care of most of the IO workload (reading rotary encoders, communicating with the main controller, sending instructions to the other PCB) and a 'smart shutter', which replaces the existing one and holds the film diagnostics tools. Future logs shall dive deeper onto each of the systems components. -

Current workflow and usage example: Part 2

02/17/2025 at 14:06 • 0 commentsDevice Fabrication

As outlined in a previous log, the design process mainly involves material selection, layout design and prepping the files for the laser cutter control software. Now it's time to see how the machine is used.

Preparing the Mechanism

Anyone who has worked with vacuum chambers knows that is usually not a breeze. While they are usually designed for modification by being quite modular, in the sense that the flanges allow changing the overall configuration flexibly and access to the different components, it still isn't a process that is trivially easy nor practical.

Therefore, ease of use was one of my primary design considerations, the idea being that changing material targets and substrates would be a quite frequent process while using the machine as a material science research tool. In the standard configuration of PLD chambers, the target manipulator is usually fixed in a flange and therefore any changes are done inside the chamber, at least in my experience.

For my design I opted for a 'capsule' arrangement, where most of the moving parts could be removed from the chamber, allowing easier 'servicing'. This design dates back to the first iteration.

The capsule itself is quite modular, consisting mainly on planar plates held together by rods, and arrangement which allowed to tune the different critical distances between the different components.

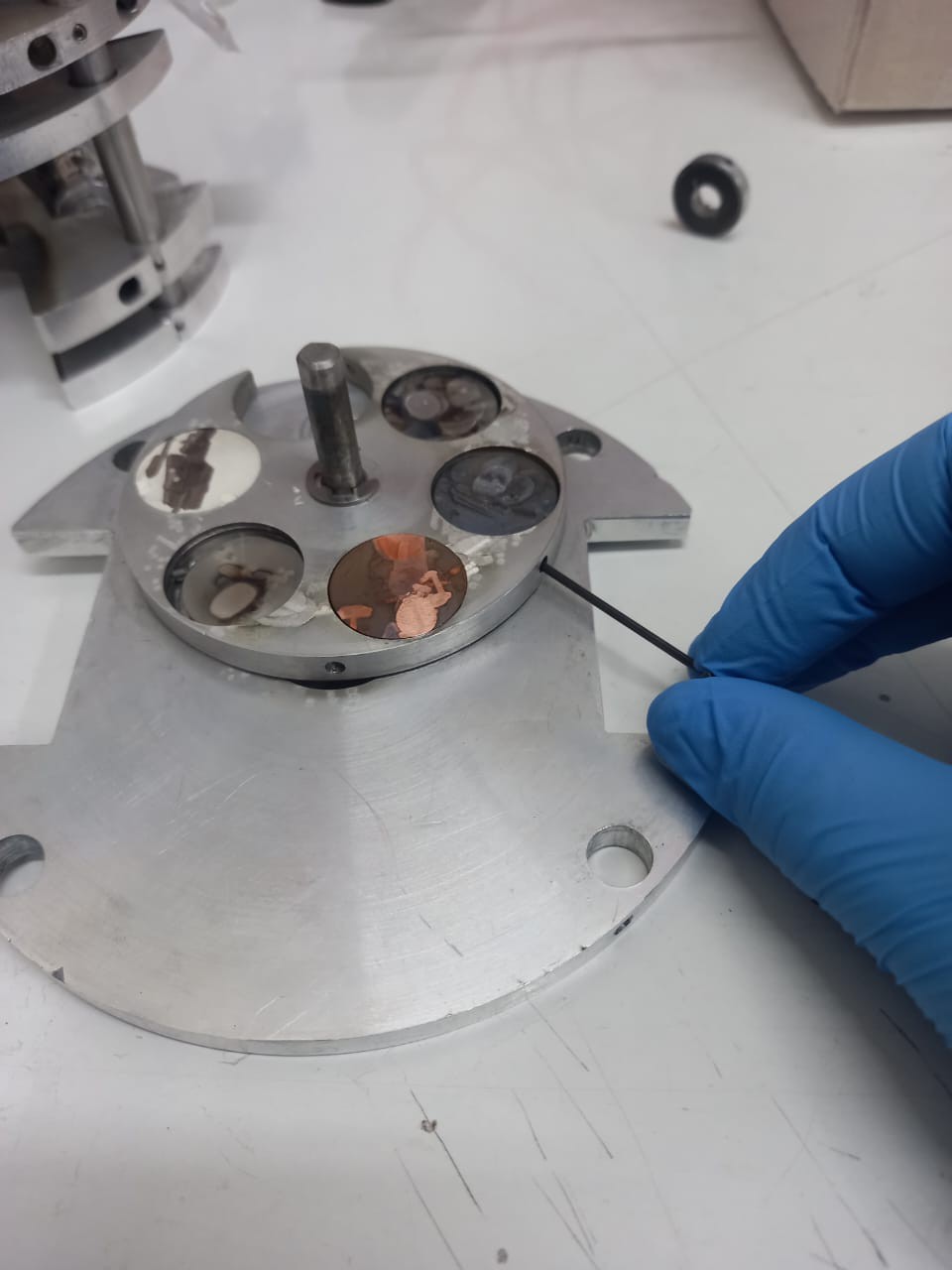

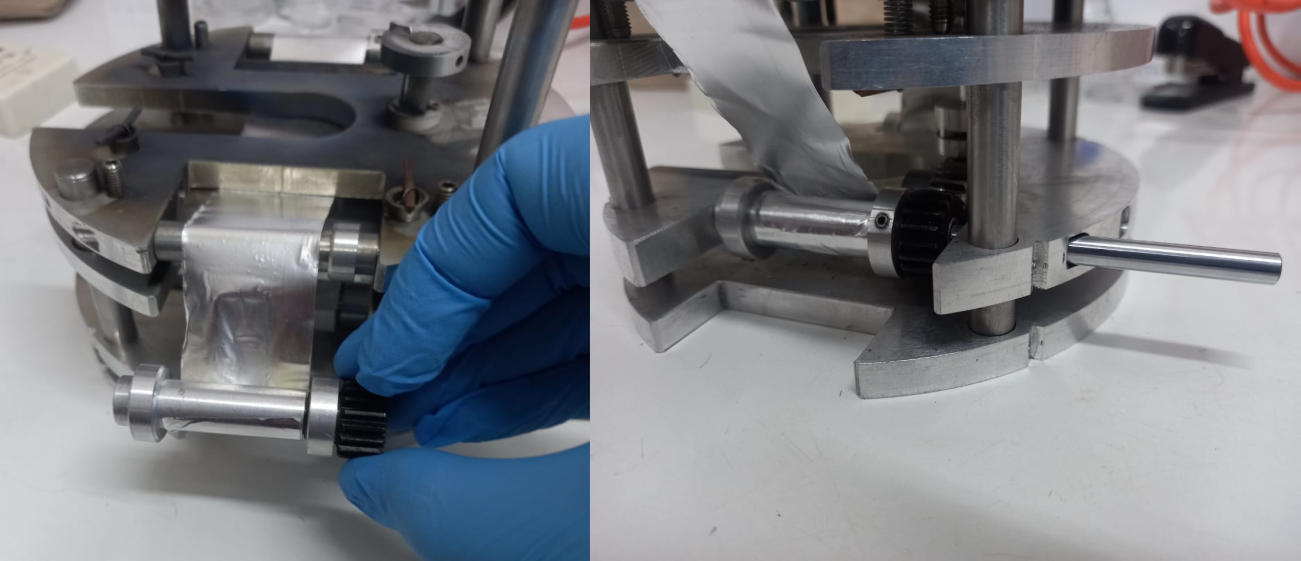

Most of the components are fastened with M3 headless screws. So, first we fix the targets:![]()

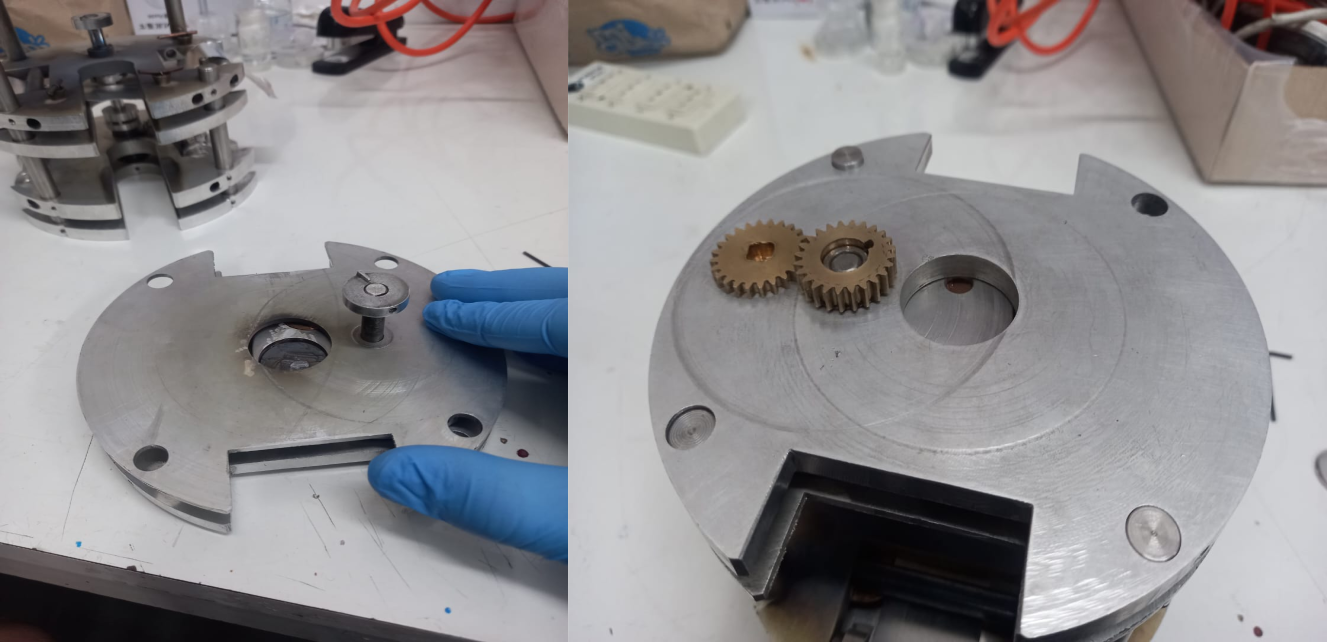

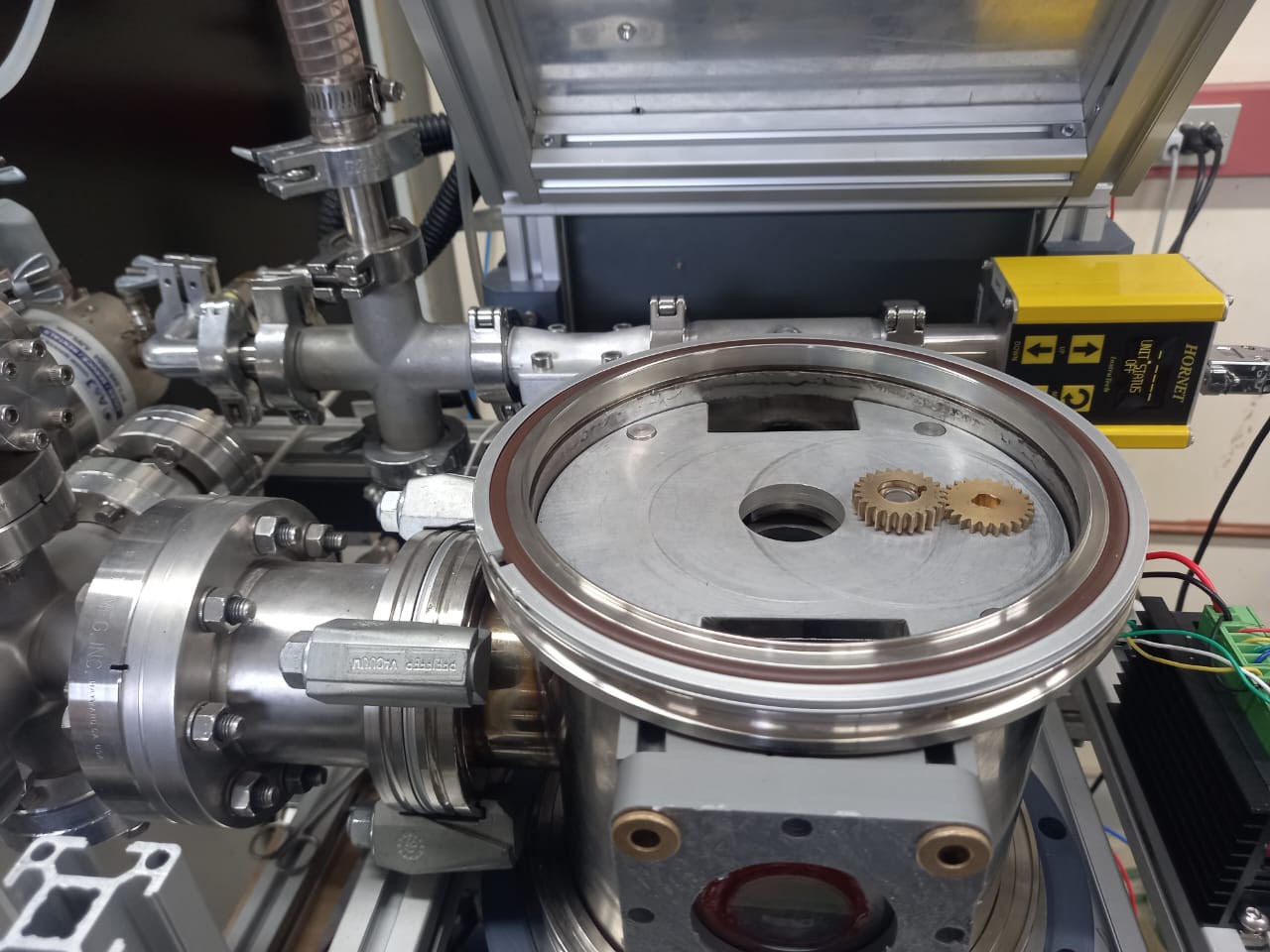

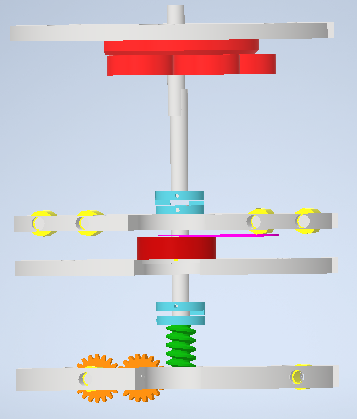

And then proceed to add the protection plate (which is mainly to avoid the contamination of the targets with aluminum from the tape machining process) and mount the top plate, along with the gears used to transmit the motion from the actuator to the main axis of the mechanism.

![]()

The gears are required to provide clearance between the actuator and the laser head. Notice the notch on the left gear, which is used to quickly couple the actuator with the mechanism.

Next one has to place the tape. Currently I'm using 35 micron aluminum foil, which is cut to a width of 35 mm and a length of about 1.5 meters. That in principle allows about 50 different mask, which in practice means that one has to change the tape after 10 deposition processes.

The mask is fixed to the moving roller with aluminum tape (I know, not ideal), which is then properly placed by means of it's removable axle.

![]()

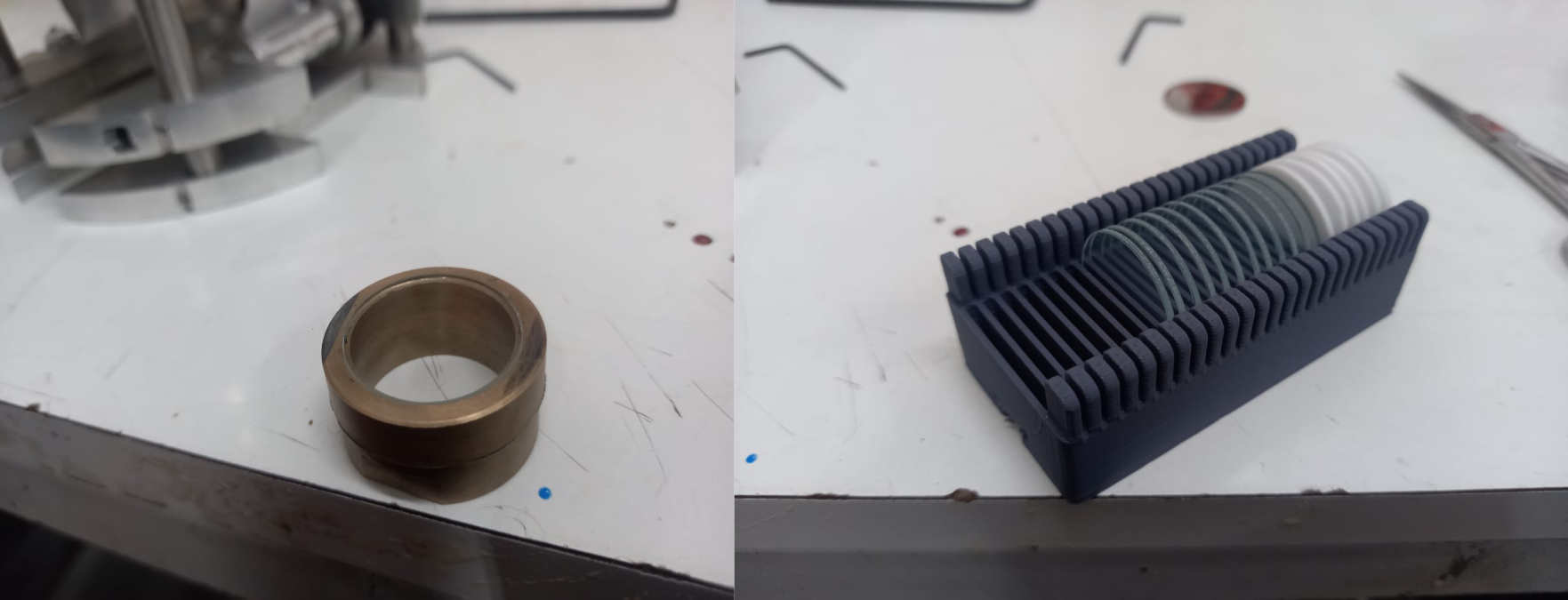

Afterwards, I usually mount the substrate. I'm using glass disks of about 25mm of diameter and 1mm thick, sold as watch covers. They are cleaned with both IP alcohol, Acetone and DI water and mounted onto the substrate holder.

![]()

The holder has a couple of notches which mates to the 'substrate plate', allowing the placement of the substrate under the mask tape without to much complications.

![]()

Now it's time to discuss an important issue with the technique: The relation between repeatability and resolution.A conundrum: Mask-substrate distance and the shutter

In case you recall, perhaps the main characteristic of the system is that the masks are machined in place, which in principle allows the whole system to 'inherit' the feature placement repeatability from the lithography tool, namely the galvo laser engraver. Now the problem here is that laser micromachining is both a dirty ( as in producing particles that may contaminate the substrate) and an aggressive (in the sense that is quite easy to damage any surface placed closely to the mask ) process. The only solution I could came up that at least partially solves this two issues is to place a shutter between the mask and the substrate during the machining process.

The shutter is basically a thin plate made of sheet steel which is coupled to the main axis of the mechanism in such a way that it covers the substrate when the aperture of the carousel is in place.While very effective to protect the substrate from laser damage and partially effective to avoid particle contamination, the issue with the shutter is that it requires a rather big clearance between mask and substrate, which negatively affects resolution.

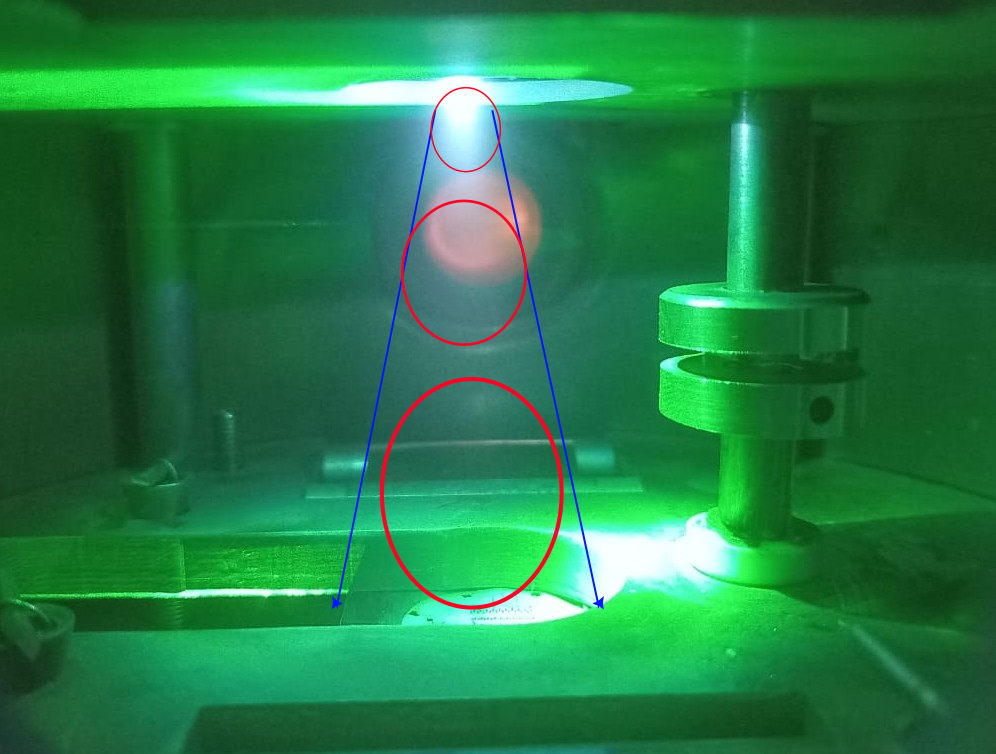

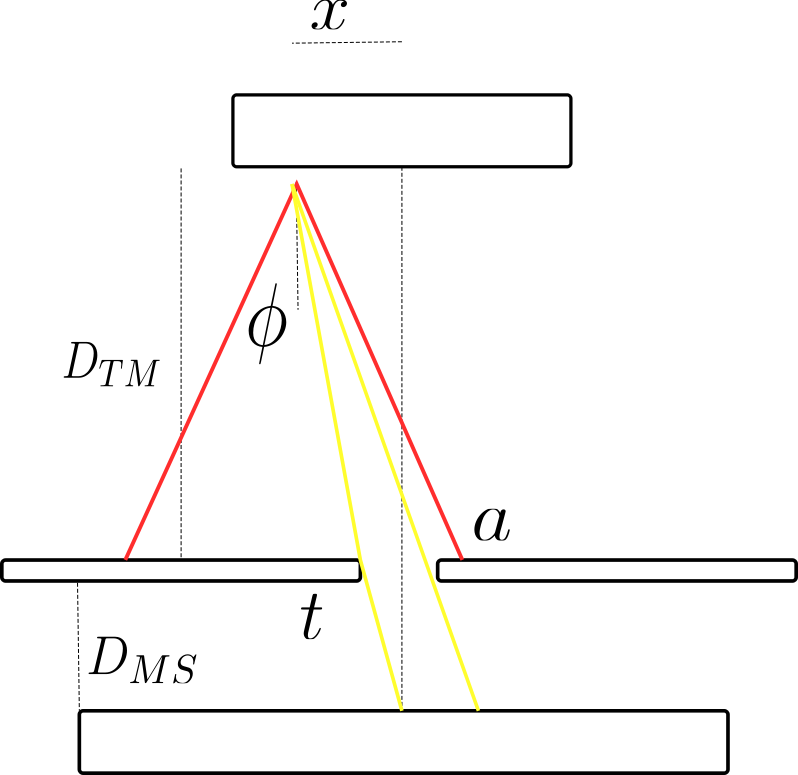

To see why it's so, let us think about how the matter flows from target to substrate. The ablation process takes place in a rather small area, which may be considered punctual for our discussion. The ablated material expands from that point with a certain angular divergence, and also some expansion due to diffusion,

![]()

As this material passes through the mask apertures, it' keeps it's angular divergence (and perhaps that divergence is subjected to certain variations at the edges of the apertures ), generating a 'shadow ' that is both larger (and perhaps displaced) from the aperture shape:

![]()

This geometrical 'blurring' is proportional to the angular divergence of the plume and the distance between the target and the substrate, being the latter the only thing that we can (easily) control.

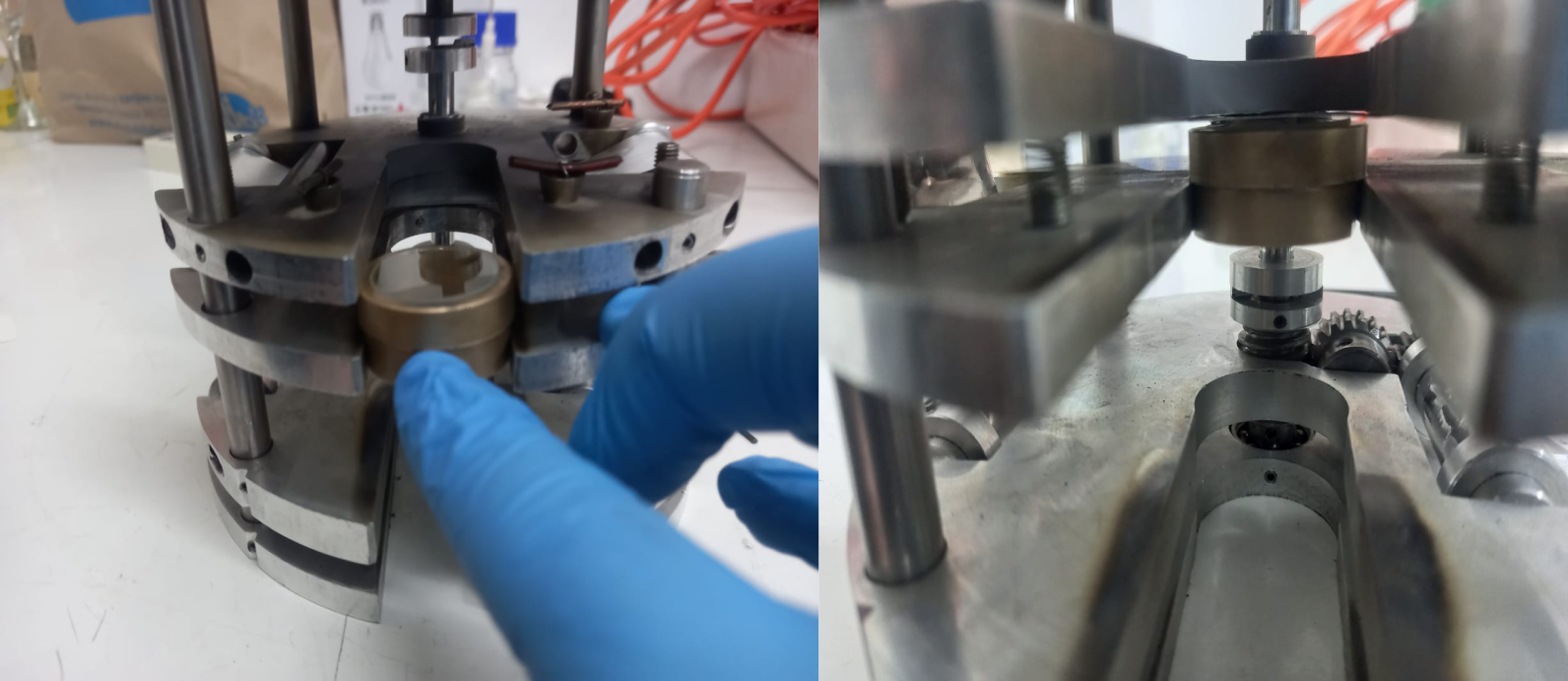

While the actual situation is slightly more complicated (in practice a deposition process will take place from multiple points over the target, and therefore the final deposit will be the sum over such points, and there are also considerations regarding gas phase diffusion and 'unconstrained' movement of the particles over the substrate ), it still quite clear that the solution in to minimize the mask-substrate distance as much as possible.A partial solution: The reciprocating substrate stage

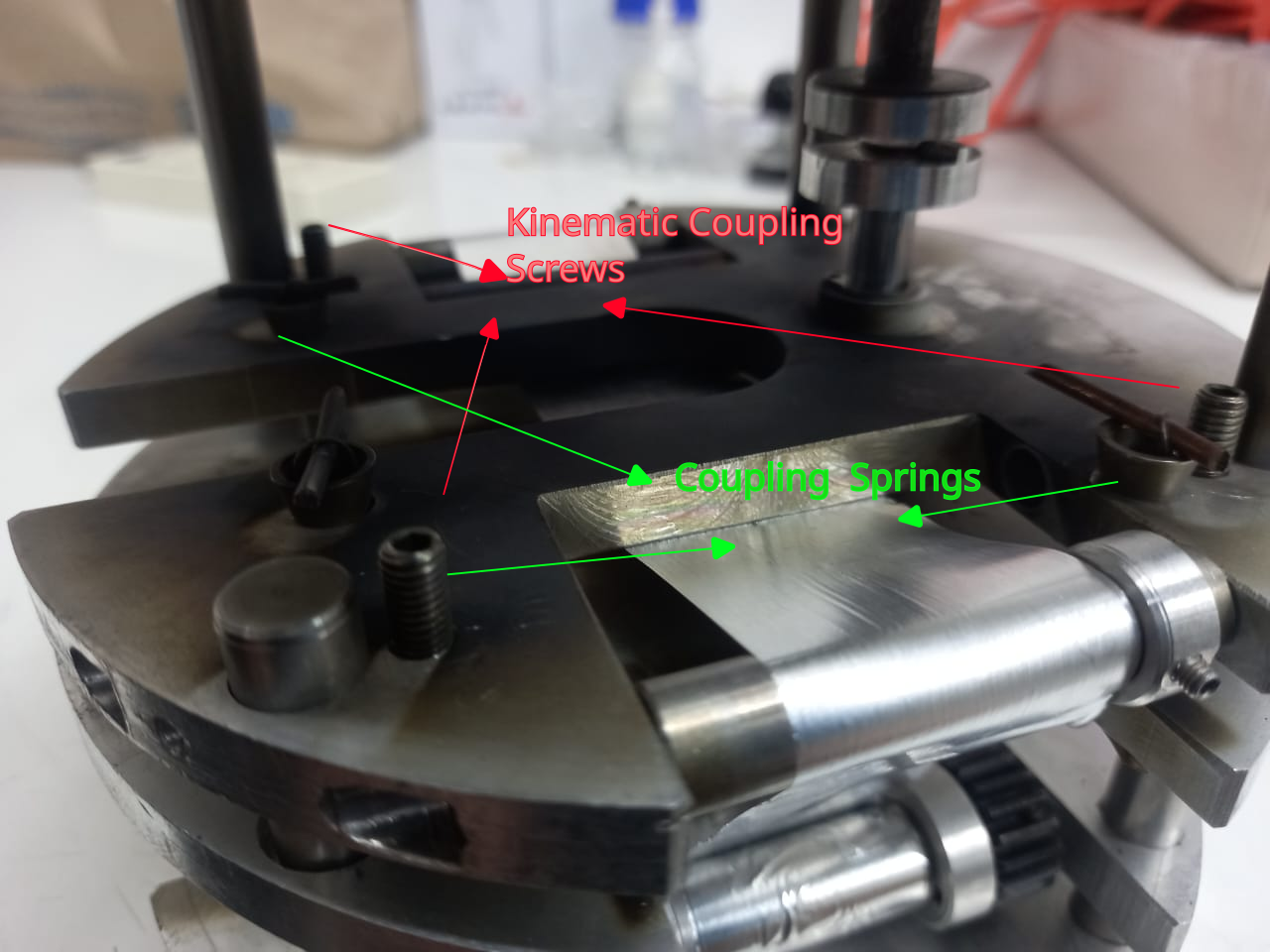

To overcome such resolution issues, I chose to move the substrate stage while the target is placed over it. While it may seem that this defeats the purpose of keeping the substrate static with respect to the laser head, I intended to take advantage of the mechanical repeatability of a kinematic coupling to solve that issue, The idea is that the substrate stage position is with respect to the mask stage determined by 3 sphere-ended screws :

![]()

Such screws allow the tuning of the plane of the substrate and the mask (something quite analog to bed leveling in a 3D printer) and the distance between those planes.

So basically what happens is that when the shutter is moved into place, it 'pushes' the substrate stage downwards a couple of millimeters. Then the mask machining takes place, and when the shutter is moved the substrate stage moves back to it`s original position, which theoretically is repeatable to within the surface roughness of the mating surfaces.

Here's a view of the process:

![]()

Along with a bit more clear view from the side. Notice the tape displacement and the partial coupler between the main axis and the worm gear.

![]()

The mechanism is still not perfect, as the stage movement is more of a tilt than a proper displacement, and the repeatability of the substrate placement could be improved considerably by using a true kinematic coupling (as the screws currently mate with some holes rather than proper constraining surfaces). Also the shutter has to be cleaned and covered with copper tape periodically due to the amount of damage associated with mask machining. Sometimes the tape is welded to the shutter, which leads to complete failure of the ongoing set of depositions.Chamber conditioning

After getting that out of the way, we shall continue describing the fabrication process. Now it's time to get the 'capsule' onto the chamber.

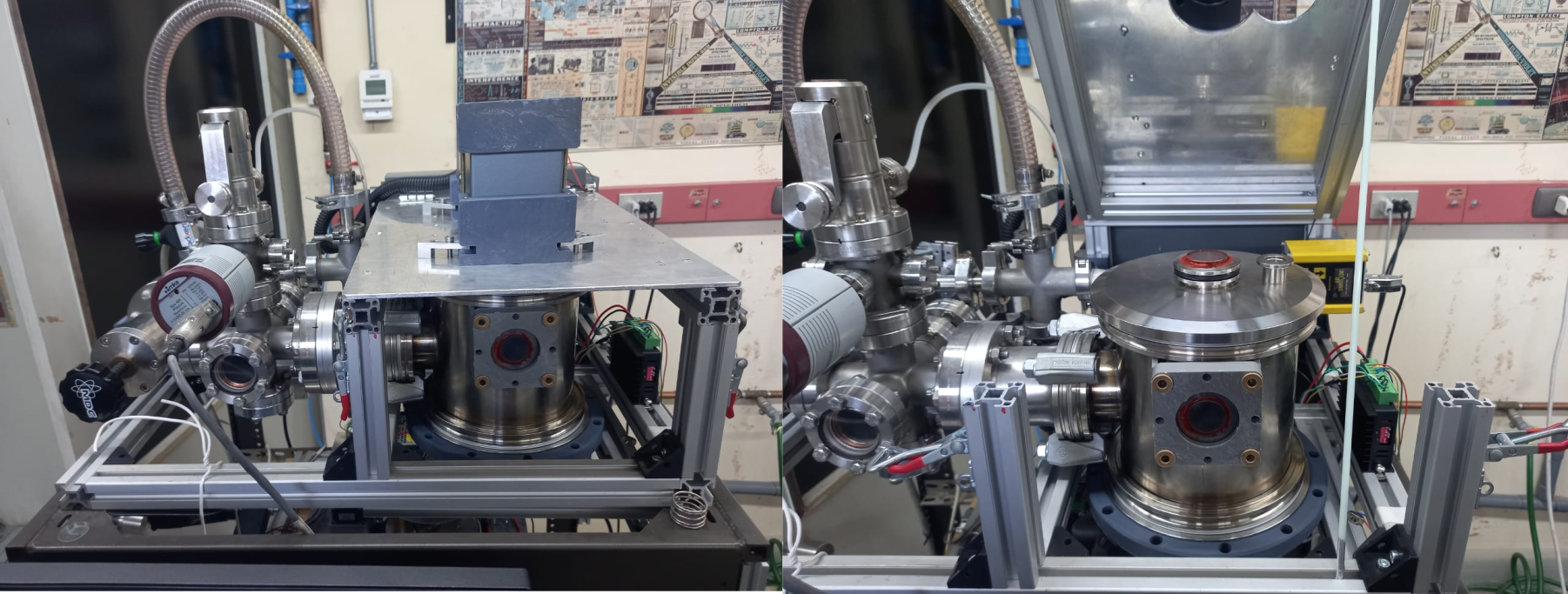

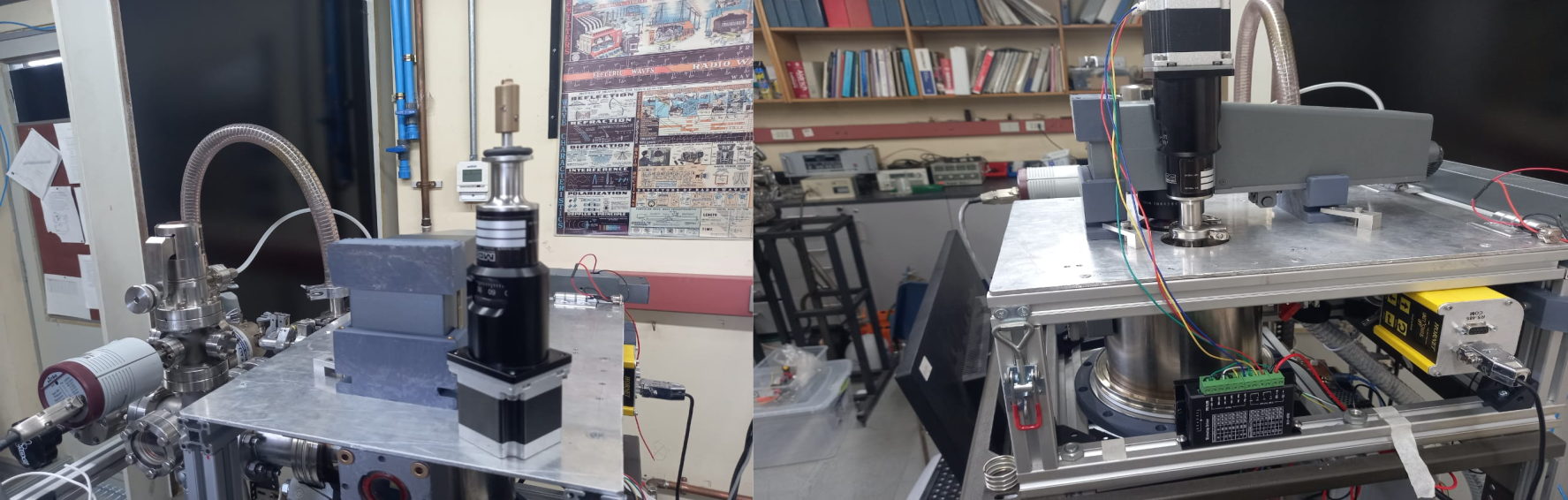

The whole system in mounted on a wheeled rack, and placed close by to the laser source. The laser is from another experiment, but the owners kindly let me use it by placing a removable mirror in the beamline.![]()

The laser is mounted onto a hinged table, which can be lifted to place the capsule in the chamber:

![]()

Then the top cover is removed and the mechanism is placed inside the chamber, taking care of placing it in the correct orientation.

![]()

Afterwards, the cover is placed again and the table secured with some clamps. Then the actuator (basically a rotary feedthrough with a custom coupler which fits the notch in the outermost gear) is inserted on the cover flange (kf16) and bolted using a light vacuum clamp.

![]()

Now everything is ready to start the actual deposition process. This writeup is getting a bit too long, so I'll leave the detailed description of it for the part III of this log.

-

Current workflow and usage example: Part 1

02/04/2025 at 20:04 • 0 commentsDefining your structures

While the system is still in a proof of concept stage, I think it's quite illustrative to see it functioning and the workflow that comes with it's usage.

My (rather long term) plans involve making relatively complex integrated systems that might prove usable in real world applications, but there's plenty of work to be done to reach such goals. For example, each material used in the devices must be rather well known (though I would argue that 'optimizing' deposition parameter should be a later step), both in terms of the deposition parameters (deposition rate, adhesion to substrate/previous films, stoichiometry, overall quality) as well as it's functional properties (conductivity for conductors, doping density in semiconductors, dielectric constant and defect density in insulators, etc.)Therefore, I think that designing test structures to measure those material and process parameters is a good place to start.

Workflow Overview

- Defining use case and structures

- Material Selection and Sourcing

- Layout Design

- Fabrication

- Testing

Intended Devices

The first step is to define the subset of materials to be used in the desired device(s). This is far from trivial, but hopefully a strong community is built around this processes which will help with streamlining such process.

For this example, I'll try to implement a bottom contacts top gate thin film transistor based on Molybdenum contacts (for adhesion), Silicon as active semiconductor and Tantalum Oxide as gate dielectric, mostly due to availability. I don't know if the band matching between Mo ans Si can lead to a functioning device, but it's worth a try.

The target carousel was designed to accept only cylindrical targets below 25.4 mm of diameter, and with a thickness not surpassing 6mm. Metallic foils can usually be accommodated also.

![]()

PVD targets are relatively expensive, so I usually look for alternatives when possible. In this case both the Si and Mo targets are actually mirrors for laser cutting machines, which are substantially cheaper, although their actual composition is a mystery,

![Targets Targets]()

Si and Mo mirrors used as target, along with a proper PLD target (CuFeO2) for reference Making the Layout

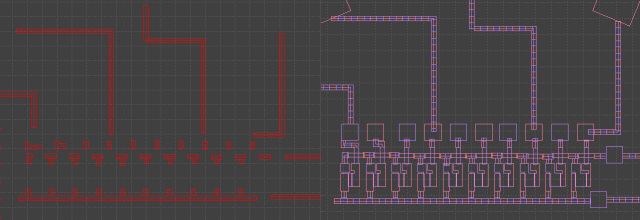

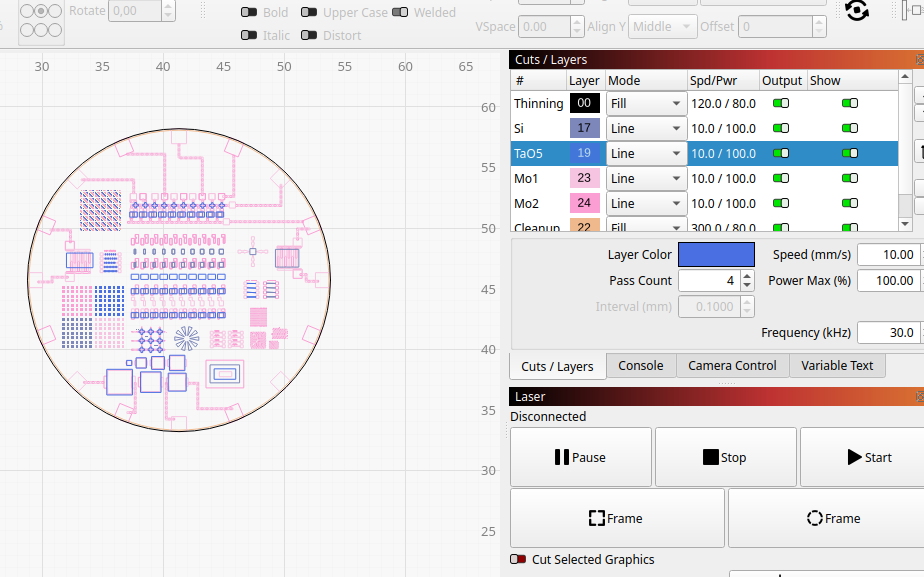

Currently I'm using Klayout through its Python API for mask design, and Lightburn for transfering the pattern. The tools are absolutely amazing, so much thanks for the respective developers, and specially to Matthias for open sourcing his tool.

FIrst, I create the layers in the layout that later will map to a deposition step through one particular map.

![]()

In this case I used a layer for Silicon, a layer for Tantalum Oxide, and two layers for the metal (due to the kind of structures to be fabricated. More on this later), as well as two auxiliary layers: a visual reference and a layer to fabricate paths ('wires').

Now one of the cool things about Klayout is it's ability define parametric cells. One may start from simple geometric primitives, and generate quite flexible structures. For example, the P_Cells.py library holds some structures I found useful initially.

![]()

Parametric Serpentine Resistor However, in these initial stages I was trying to diagnose some capabilities of the machine, and thus I was trying to implement different test structures to gather information such as achievable linewidth, step coverage, gap size, degree of alignment and registration, etc. I opted to generate structures where a geometric variable varied over a certain range, and for those cases I haven't been able to generate a proper PCell implementation, selecting straightforward coding instead:

![]()

The file Struct_lib holds some functions to generate those kind of structures. As this was a demonstrative layout, I was interested in illustrating the process of making a TFT, so I kind of made an 'step by step' illustration;

![]()

Now to connect the structures we have to add wires, which leads to an important issue with shadow masks: As they are self supported, not only they cannot replicate some geometries (think of a donut, for example) but also structures with long, unsupported features (consider, for example, the negative space of a pair of interdigitated electrodes) might deform under their own weight.

The solution is to make such structures in more than one deposition process, which is well suited for the current system. That's why some material layers have more tan one instance, to subdivide the structures into more than one.

To make the subdivision process easier, I use auxiliary layers (such as 'paths', in this case) to fabricate the original structures, and then the layout is fed to a 'Paths Post-processing' script which performs the required actions.

![]()

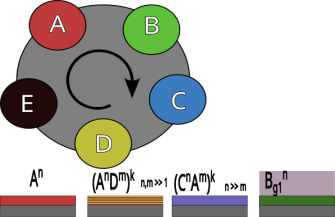

Now once the complete layout is ready, the GDS file is exported as an SVG using the script provided by Matthias onto LightBurn.

![]()

Here each (functional) layer in the layout is mapped to a given cut layer, where the laser parameters can be tuned according to the kind of structures. Currently the laser machining is mostly a photothermal process, and thus apertures with less perimeter then to require less passes. Each layer is thus selected (along with auxiliary processes such as mask thinnng and cleanup) and saved independently.

![]()

The filename is currently important for the automation process, I use the convention:

step[target1(time)target2(time)...]repetition.lbrn2

which is then intepreted by the machine control software. For example

0[F2B4]2.lbrn2

will be interpreted by the control software as the first deposition step, where a cycle of 2 minutes of deposition for target in position 'F' and 4 minutes of target in position 'B' is repeated twice,

The syntax is recursive, to allow the fabrication of the different possibilities for each layer.

![]()

So the folder fed to the control software looks something like:

![]()

Where each step of the process is assigned a given mask and a certain deposition parameters.

The control software and fabrication process will be outlined in the next log.

-

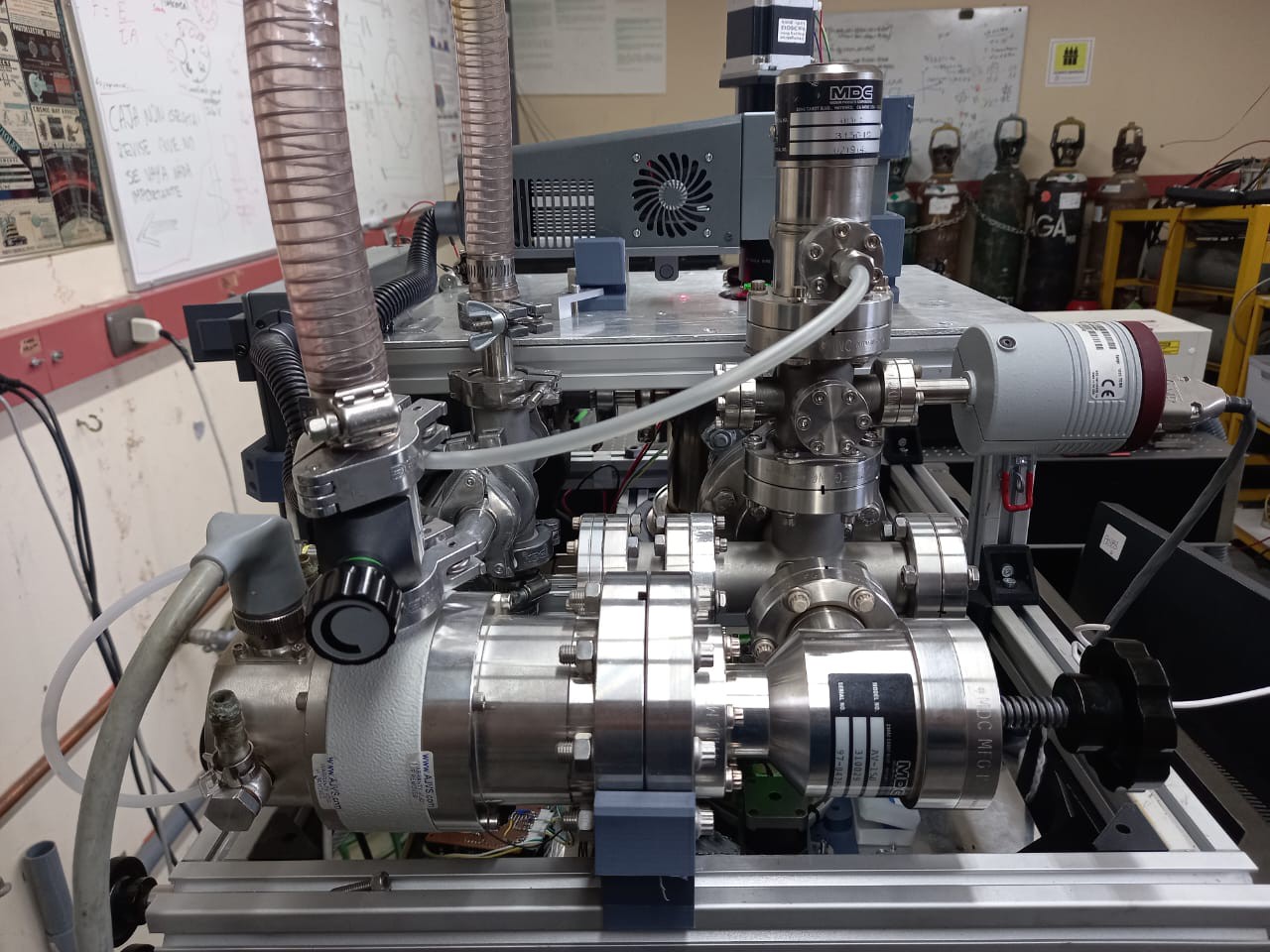

The Vacuum System

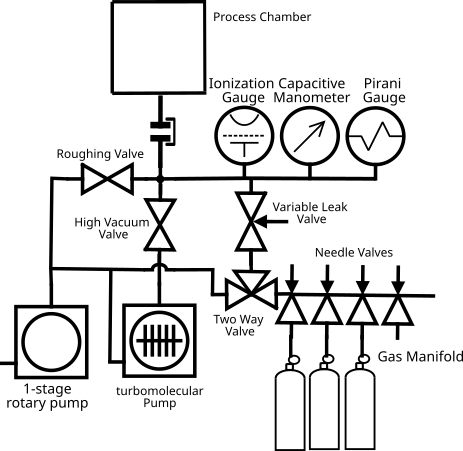

02/04/2025 at 19:30 • 0 commentsSystem Overview

Performing the deposition in a controlled atmosphere is essential to generate films and structures with the appropriate characteristics. A decent vacuum ( ideally under 1e-6 torr ) and perhaps different low pressure reactive species (for examples O2 in the order of 1e-2 torr for oxides) must be alternated in quick succession.

Usually high vacuum pumps such as turbomolecular pumps operate within a narrow range of conditions, and turning them on and off is a time consuming process. Therefore, is important to design a vacuum system with a set of valves which allow fast variations among different atmospheres.

![]()

This implementation took advantage of several components that I had available, which is far from ideal.

![Vacuum side view Vacuum side view]()

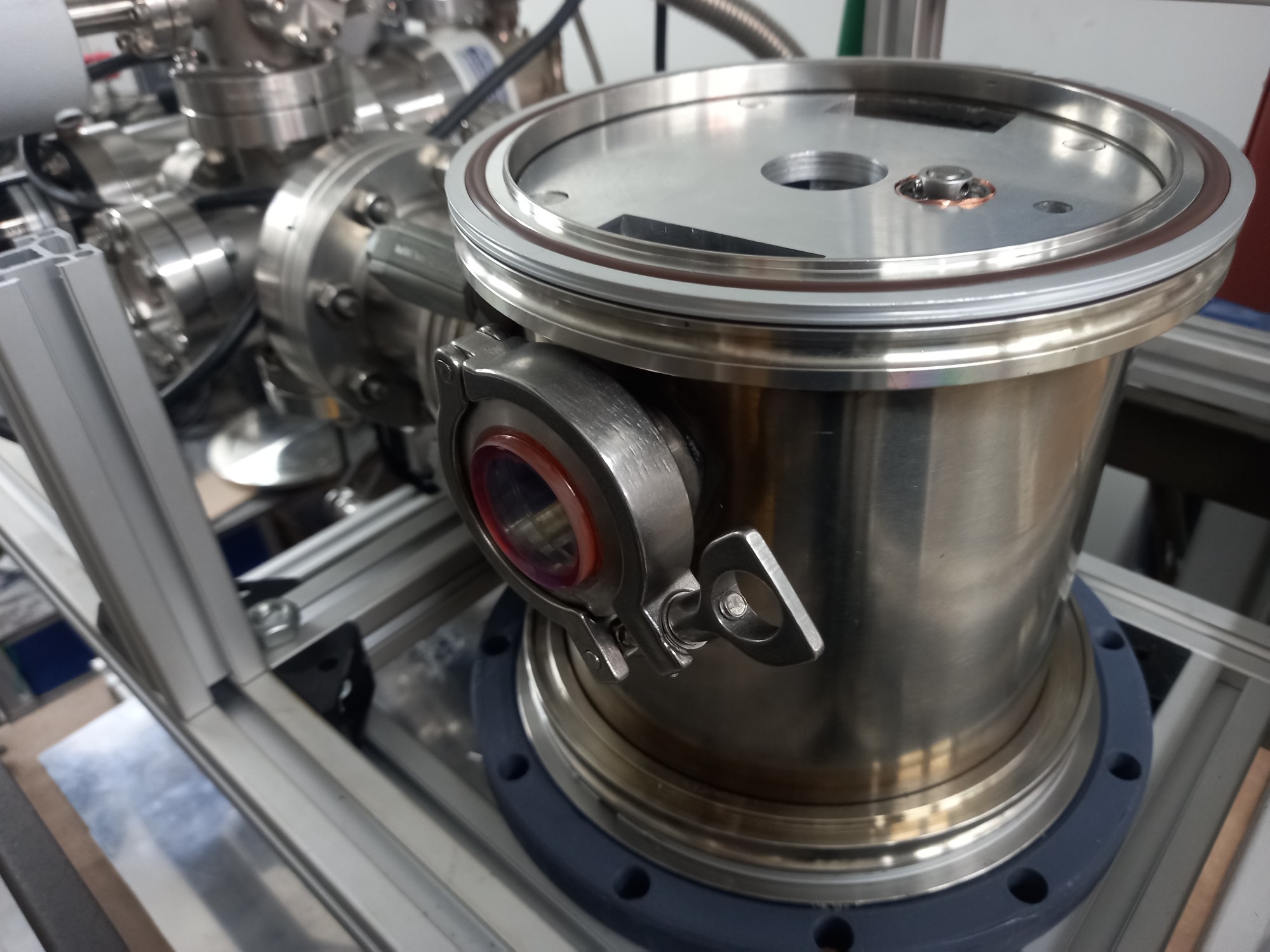

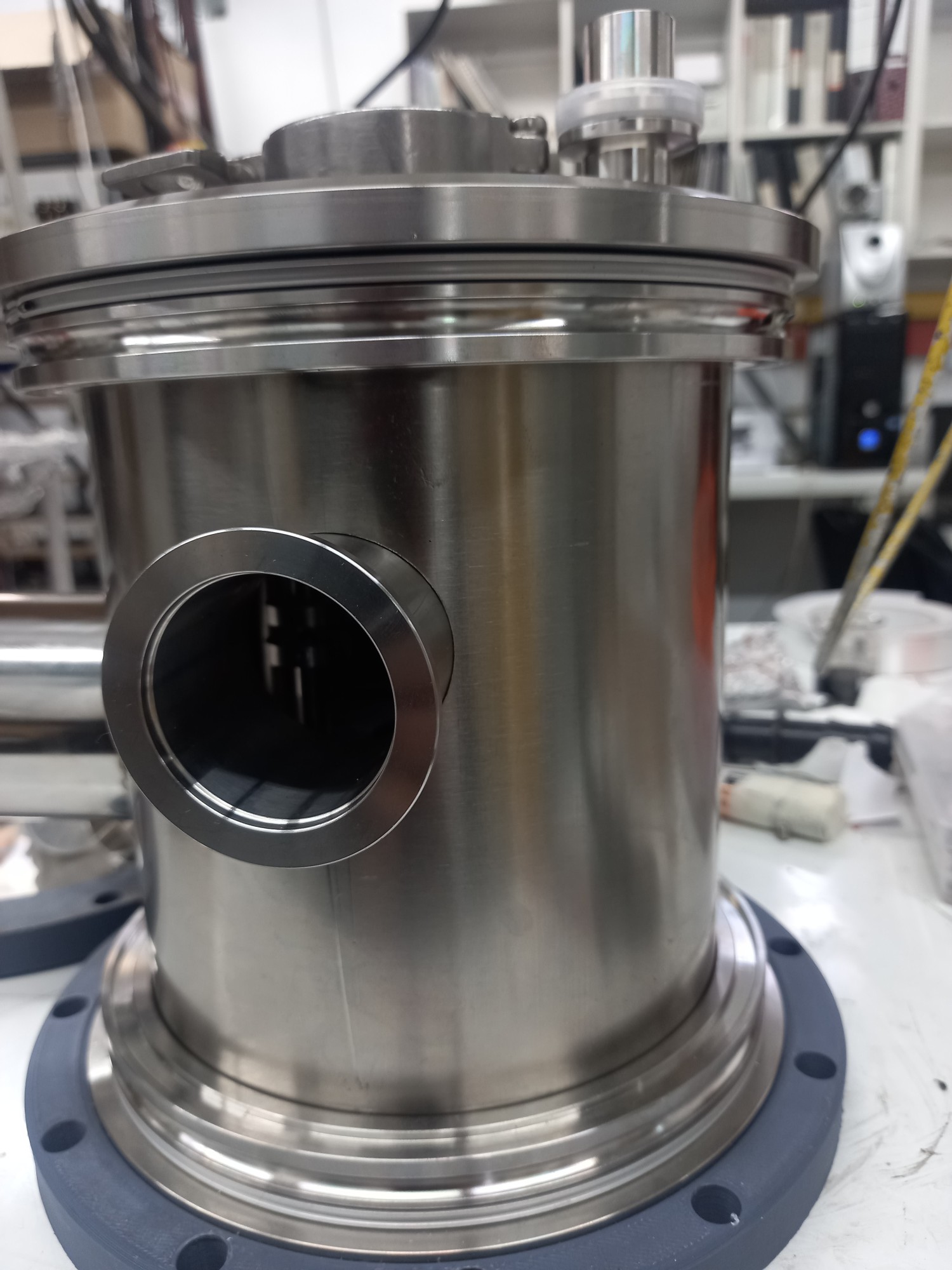

The Process Chamber

![]()

While most components where taken 'off the shelf', the mechanism chamber had several dimensional requirements (specially regarding the target-substrate distance and the different lasers focal lengths) that could only be met with a custom chamber. As those are very expensive, I had to manufacture it myself.

The cylindrical shape is quite standard due to it's ease of machining and good distribution of the pressure differential related efforts. I used a standard size for flanges, choosing ISO160 for their ease of use. I bought several Inner weld flanges from Aliexpress, as well as a 154mm OD x 2mm thick stainless steel pipe. Curiously I couldn't find any vendor from where I'm from, so I had to buy it abroad as well.![]()

The chamber was machined to length in a lathe, and then the aperture for the flanges where milled.

The KF40 flanges, initially though as viewports and for plume diagnostics, where bought from Aliexpress (they are fairly inexpensive) and then machined to provide the right fit to the main chamber:

![]()

The same process was made for the ISO63 flange intended initially as a coupling to an existing turbomolecular pump.

After making sure that the tolerances were acceptable, I proceeded to TIG weld the chamber together.

![]()

![]()

While definitively not very pretty welds, after a few adjustments they seemed to hold a decent vacuum :).

The process for the covers was quite similar: They also required custom apertures for the laser windows and manipulators. By mistake I bought KF160 instead of the proper ISO160 blind plates, but fortunately both standards are interchangeable.

![]()

After the holes where bored, cheap KF(40/25/16) flanges were welded in place.

-

Making the 'Simple as Possible' Mechanism

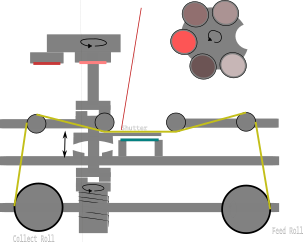

02/04/2025 at 15:40 • 0 commentsDefining the process

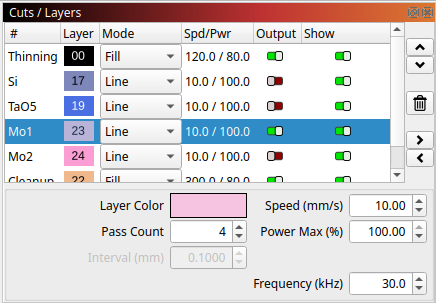

To being able to flexibly fabricate the intended structures, the following process was devised:

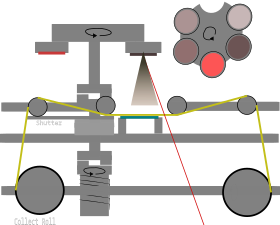

![]()

One starts with a bare substrate, covered by the unmarked mask 'web'

and a shutter between them. The target carousel is placed in such a way that it lets laser light pass through it. Either under vacuum or an unreactive gas, the apertures are defined.When the apertures are cut, the shutter is removed and the proper atmosphere is set onto the chamber. Then the proper deposition process is performed (either from a single target or a given combination).

![]()

Once the deposition step is completed, the mask web is moved until only unmarked tape covers the substrate. This sequence may be repeated until the mask is completely consumed.

Evidently the shutter is required to protect the substrate from debris and laser ablation. It quite a compromise, as the distance between shadow mask and substrate heavily influences the achievable resolution.

As a solution, the mechanism is designed in such a way that whenever the shutter moves into place, it pushes the substrate stage onto a lower position. When the substrate is uncovered, the substrate stage reciprocates back, with it's position determined by a simplified kinematic coupling.

Now such mechanism seems to have a fair bit of degrees of freedom: Target carousel, shutter, and mask roll movement is required. However, they move in a fairly well defined sequence, so in principle all movements could be partially coupled to one another in order to reduce the required actuation elements.

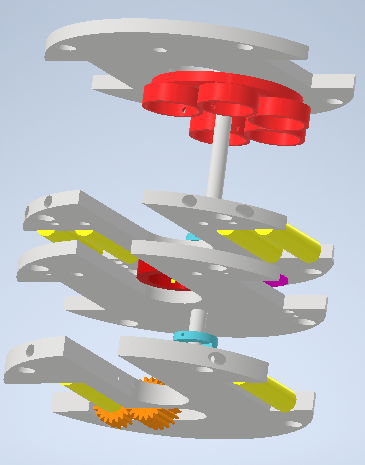

A First Iteration

![]()

![]()

The Prototype

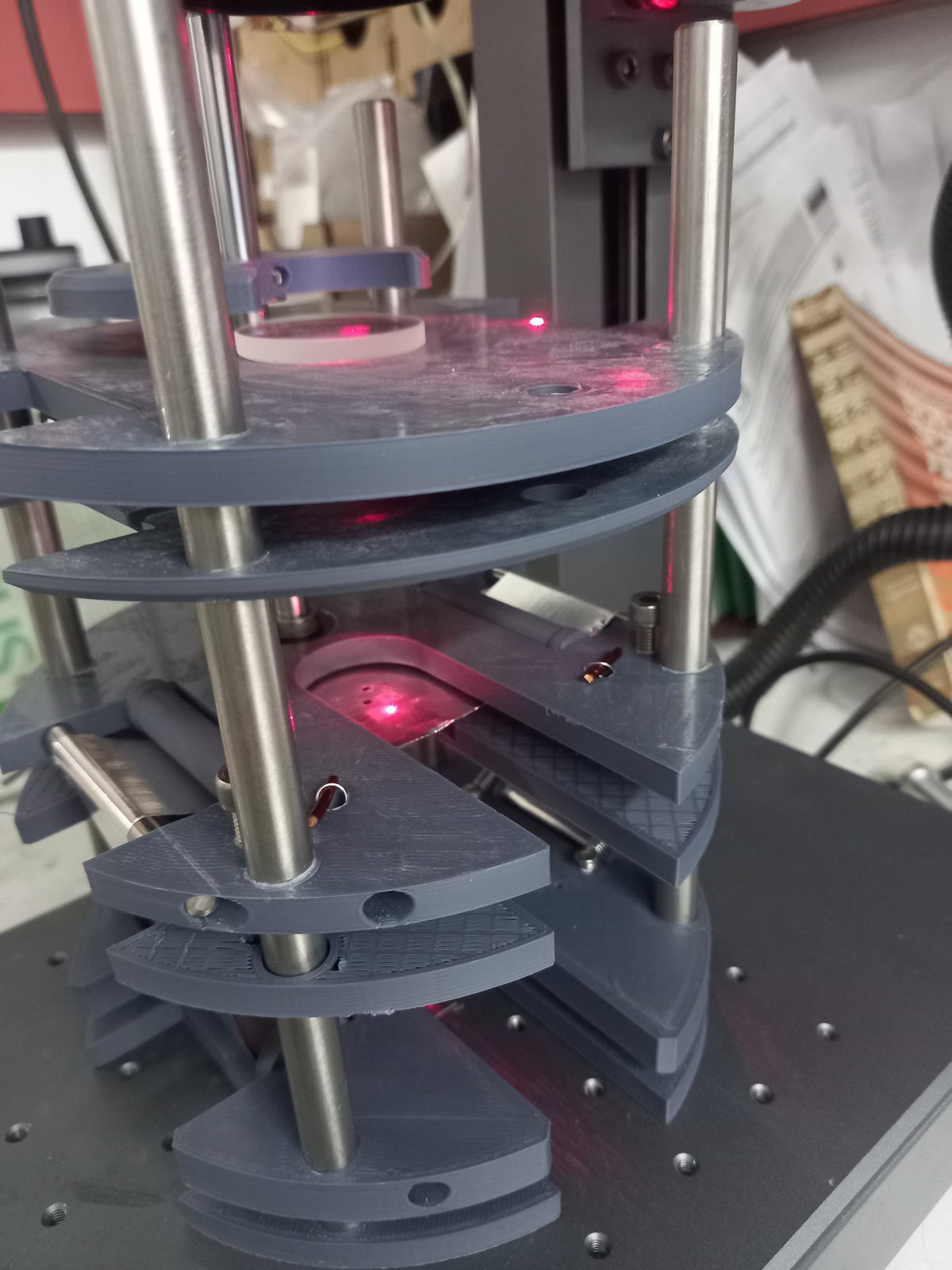

While 3D printed components are usually not vacuum compatible (at least not as is), they were a great tool to test the ideas involved, and gradually start implementing the final pieces. Here are a couple of pictures of the process:

![]()

It was crucial to test the resistance of the tape after marking.

Actual Mechanism Fabrication

As the mechanism is mostly composed of planar 'plates' with different apertures, it's well suited for processing with laser cutters or waterjets. However, I wasn't very confident on my designs, so I rather chose to fabricate the whole assembly out of duraluminum stock.

I started from a 6' cylinder , and turned it on the lathe to the appropriate (149 mm) diameter.

![]()

After that, all the common perforations were made in a (relatively unsuccessful) attempt to keep al the plates and moving axis aligned. The common features between plates were machined as well:

![]()

After that, each plate was cut from the main block (a royal PITA)

![]()

And finished on the lathe:

![]()

Or given some extra details in the mill:

![]()

The process was repeated several times until the mechanism was completed:

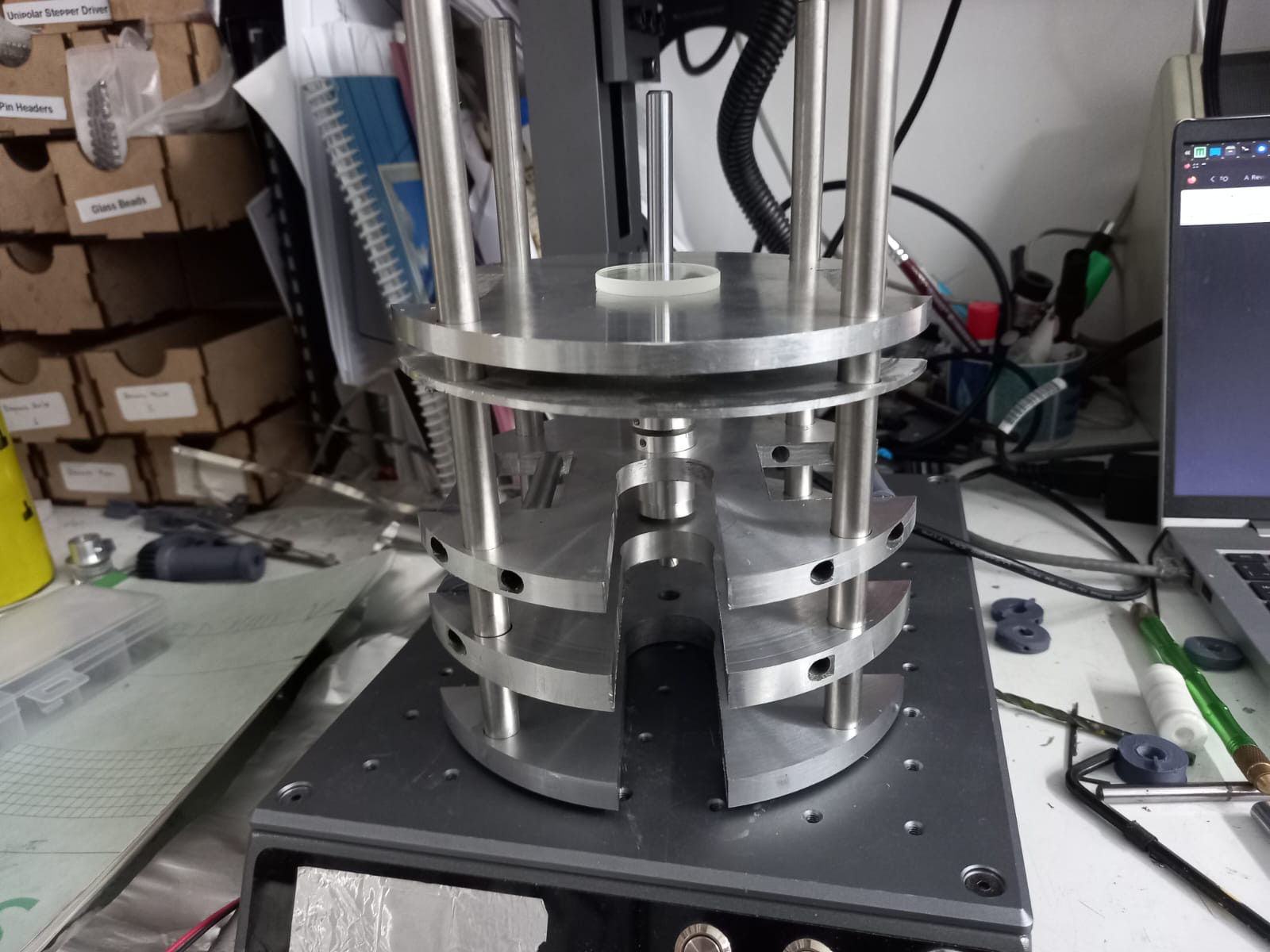

![]()

The remaining components (rollers, target carousel, couplings) were machined with standard techniques (and in those cases it actually made sense to do so).

Evidently the manufacture could be simplified a lot using the proper tools to fabricate the plates, so I'm currently working on designing a mostly laser-cut version.

Rapid Prototyping of Solid State Devices

A relatively inexpensive and flexible tool to generate heterostructures, devices and integrated systems

Sebastián Elgueta

Sebastián Elgueta